8. Global Cauchy theorem PDF TEX

Chains and cycles

Chains and cycles

Suppose \(\gamma_{1}, \ldots, \gamma_{n}\) are paths in \(\mathbb C\), and set \(K=\gamma_{1}^{*} \cup \cdots \cup \gamma_{n}^{*}\). Let \(C(K)\) be the vector space of continuous functions on \(K\). Each \(\gamma_{i}\) induces a linear functional \(\tilde{\gamma}_{i}\) on \(C(K)\), by the formula \[\tilde{\gamma}_{i}(f)=\int_{\gamma_{i}} f(z) d z.\]

Define \(\tilde{\Gamma}=\tilde{\gamma}_{1}+\cdots+\tilde{\gamma}_{n}\) or more explicitly, \[\tilde{\Gamma}(f)=\tilde{\gamma}_{1}(f)+\cdots+\tilde{\gamma}_{n}(f), \quad \text{ for }\quad f \in C(K). \tag{*}\]

The relation (*) suggests that we introduce a “formal sum” \[\Gamma=\gamma_{1} \dot{+} \cdots \dot{+} \gamma_{n},\] and define \[\int_{\Gamma} f(z) d z=\tilde{\Gamma}(f)=\sum_{i=1}^n\int_{\gamma_{i}} f(z) d z, \quad \text{ for }\quad f \in C(K).\]

Let \(\gamma_{1}, \ldots, \gamma_{n}\) be paths such that \(\gamma_{i}^{*} \subset \Omega\) for \(1 \leq i \leq n\).

Let \(\Gamma\) be a formal sum as before given by \[\Gamma=\gamma_{1} \dot{+} \cdots \dot{+} \gamma_{n}. \tag{**}\] Then we say that \(\Gamma\) is a chain in \(\Omega\).

If there exists a representation of a chain \(\Gamma\) such that each \(\gamma_{i}\) is a closed path in \(\Omega\), then we say that \(\Gamma\) is a cycle in \(\Omega\).

By a combinatorial argument, it can be shown that a chain \(\Gamma\) is a cycle if and only if in any representation of \(\Gamma\), the initial and end points of \(\gamma_{i}\) are identical in pairs.

If (**) holds, then we define \(\Gamma^*=\gamma_{1}^{*} \cup \cdots \cup \gamma_{n}^{*}\).

The relation (**) means that we are adding paths in the context of adding linear functionals (*); otherwise, it would not be meaningful.

If \(\Gamma\) is a cycle and \(\alpha \notin \Gamma^{*}\), we define the index of \(\alpha\) with respect to \(\Gamma\) by \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} \frac{d z}{z-\alpha}.\]

Obviously, (**) implies \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=\sum_{i=1}^{n} \operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{i}}(\alpha).\]

If each \(\gamma_{i}\) in (**) is replaced by its opposite path \(-\gamma_i\), the resulting chain will be denoted by \(-\Gamma\). Then \[\int_{-\Gamma} f(z) d z=-\int_{\Gamma} f(z) d z \quad \text{ for } \quad f \in C\left(\Gamma^{*}\right).\]

In particular, \(\operatorname{Ind}_{-\Gamma}(\alpha)=-\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)\) if \(\Gamma\) is a cycle and \(\alpha \notin \Gamma^{*}\).

Chains can be added and subtracted in the obvious way, by adding or subtracting the corresponding functionals.

The statement \(\Gamma=k_1\Gamma_{1} \dot{+} k_2\Gamma_{2}\) for any integers \(k_1, k_2\in\mathbb Z\) means that \[\int_{\Gamma} f(z) d z=k_1\int_{\Gamma_{1}} f(z) d z+k_2\int_{\Gamma_{2}} f(z) d z \quad \text{ for all }\quad f \in C\left(\Gamma_{1}^{*} \cup \Gamma_{2}^{*}\right).\]

Finally, note that a chain may be represented as a sum of paths in many ways. To say that \[\gamma_{1} \dot{+} \cdots \dot{+}\gamma_{n}=\delta_{1} \dot{+} \cdots \dot{+} \delta_{k}\] means simply that \[\sum_{i=1}^n \int_{\gamma_i} f(z) d z=\sum_{j=1}^k \int_{\delta_j} f(z) d z\] for every \(f\) that is continuous on \(\gamma_{1}^{*} \cup \cdots \cup \gamma_{n}^{*} \cup \delta_{1}^{*} \cup \cdots \cup \delta_{k}^{*}\).

In particular, a cycle may very well be represented as a sum of paths that are not closed.

Global Cauchy’s theorem

Global Cauchy’s theorem

Suppose \(f \in H(\Omega)\), where \(\Omega\) is an arbitrary open set in the complex plane.

If \(\Gamma\) is a cycle in \(\Omega\) that satisfies \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=0\) for every \(\alpha \not \in \Omega\), then \[f(z) \cdot \operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(z)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} \frac{f(w)}{w-z} d w \quad \text { for } \quad z \in \Omega\setminus\Gamma^{*}, \tag{A}\] and \[\int_{\Gamma} f(z) d z=0, \tag{B}\]

If \(\Gamma_{0}\) and \(\Gamma_{1}\) are cycles in \(\Omega\) such that \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{0}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{1}}(\alpha)\) for every \(\alpha \not \in \Omega\), then \[\int_{\Gamma_{0}} f(z) d z=\int_{\Gamma_{1}} f(z) d z. \tag{C}\]

Proof: The function \(g\) defined in \(\Omega \times \Omega\) by \[g(z, w)= \begin{cases}\frac{f(w)-f(z)}{w-z} & \text { if } w \neq z,\\ f^{\prime}(z) & \text { if } w=z, \end{cases}\] is continuous in \(\Omega \times \Omega\) (see the previous lecture).

Hence we can define

\[h(z)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} g(z, w) d w \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in \Omega.\]

For \(z \in \Omega\setminus\Gamma^{*}\), the Cauchy formula (A) is clearly equivalent to the assertion that \[h(z)=0.\]

To prove that \(h(z)=0\), let us first prove that \(h \in H(\Omega)\).

We first show that \(h\) is continuous in \(\Omega\).

Observe that \(g\) is uniformly continuous on every compact subset of \(\Omega \times \Omega\). If \(z \in \Omega\) and \((z_{n})_{n\in\mathbb N} \subseteq \Omega\), and \(\lim_{n\to \infty}z_{n} = z\), it follows that \(\overline{\{z_n:n\in\mathbb N\}}\times\Gamma^{*}\) is a compact subset of \(\Omega\times \Omega\), and consequently \(\lim_{n\to \infty}g\left(z_{n}, w\right) = g(z, w)\) uniformly for \(w \in \Gamma^{*}\).

Hence \(\lim_{n\to \infty}h\left(z_{n}\right) = h(z)\), proving that \(h\) is continuous in \(\Omega\).

Let \(\Delta\) be a closed triangle in \(\Omega\). Then by Fubini’s theorem \[\int_{\partial \Delta} h(z) d z=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma}\left(\int_{\partial \Delta} g(z, w) d z\right) d w.\]

For each \(w \in \Omega\) the function \(z \mapsto g(z, w)\) is holomorphic in \(\Omega\), since he singularity at \(z=w\) is removable.

The inner integral over \(\partial \Delta\) is therefore \(0\) for every \(w \in \Gamma^{*}\). Thus Morera’s theorem shows now that \(h \in H(\Omega)\) as desired.

Let \(\Omega_{1}=\{z\in\mathbb C:\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(z)= 0\}\). Then \(\Omega^c\subseteq \Omega_{1}\), since \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)= 0\) for all \(\alpha\in \Omega^c\). Moreover, \(\Omega_1\) is open since the index function \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}:\mathbb C\setminus\Gamma^*\to \mathbb Z\) is continuous. Also \(\Omega_{1}\) contains the unbounded component of the complement of \(\Gamma^{*}\), since \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(z)\) is \(0\) there.

Define \[h_{1}(z)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} \frac{f(w)}{w-z} d w \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in \Omega_{1}.\]

If \(z \in \Omega \cap \Omega_{1}\), the definition of \(\Omega_{1}\) makes it clear that \(h_{1}(z)=h(z)\).

Hence there is a function \(\varphi \in H\left(\Omega \cup \Omega_{1}\right)\) whose restriction to \(\Omega\) is \(h\) and whose restriction to \(\Omega_{1}\) is \(h_{1}\).

Since \(\Omega \cup \Omega_{1}=\mathbb C\), thus \(\varphi\) is an entire function. Hence \[\lim _{|z| \rightarrow \infty} \varphi(z)=\lim _{|z| \rightarrow \infty} h_{1}(z)=0.\]

Liouville’s theorem implies now that \(\varphi(z)=0\) for every \(z\in\mathbb C\). This proves that \(h(z)=0\), and hence (A).

To deduce (B) from (A), pick \(a \in \Omega\setminus\Gamma^{*}\) and define \[F(z)=(z-a) f(z).\] Since \(F(a)=0\), and using (A) we obtain \[\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} f(z) d z=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} \frac{F(z)}{z-a} d z=F(a) \cdot \operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(a)=0.\]

To prove (C) let \(\Gamma=\Gamma_{1}-\Gamma_{0}\). By our assumptions \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=0\) for every \(\alpha\in\Omega^c\), hence by (B) we obtain \[\int_{\Gamma} f(z) d z=0.\]

This is equivalent to statement (C): \[\int_{\Gamma_{0}} f(z) d z=\int_{\Gamma_{1}} f(z) d z.\] since \(\Gamma=\Gamma_{1}-\Gamma_{0}\). This completes the proof.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Let \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) be an open set and \(f \in H(\Omega)\), and let \(\Gamma\) be a cycle in \(\Omega\). Then the following statements are equivalent:

\[f(z) \cdot \operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(z)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} \frac{f(w)}{w-z} d w \quad \text { for } \quad z \in \Omega\setminus\Gamma^{*}.\]

\[\int_{\Gamma} f(z) d z=0.\]

\[\begin{aligned} \operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=0\quad \text{ for every } \quad \alpha \in \mathbb C\setminus\Omega. \end{aligned}\]

Proof (i) \(\implies\) (ii): Pick \(a \in \Omega\setminus\Gamma^{*}\) and define \[F(z)=(z-a) f(z).\] Since \(F(a)=0\), and using (i) we obtain \[\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} f(z) d z=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} \frac{F(z)}{z-a} d z=F(a) \cdot \operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(a)=0.\quad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\] Proof (ii) \(\implies\) (iii): For \(a\in \mathbb C\setminus\Omega\) the function \(f(z)=(z-a)^{-1}\) is holomorphic in \(\Omega\). By (ii), since \(\Gamma\subseteq\Omega\), we obtain \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(a)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} \frac{1}{z-a} d z=0.\] Proof (iii) \(\implies\) (i): This implication follows from the global Cauchy theorem. This completes the proof of the corollary. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remarks.

If \(\gamma\) is a closed path in a convex region \(\Omega\) and if \(\alpha \notin \Omega\), an application of the Cauchy theorem for convex sets to \(f(z)=(z-\alpha)^{-1}\) shows that \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(\alpha)=0.\]

Therefore the hypothesis of the global Cauchy theorem is therefore satisfied by every cycle in \(\Omega\) if \(\Omega\) is convex.

This shows that the global Cauchy theorem generalizes Cauchy theorem and the Cauchy integral theorem for convex regions.

Remarks.

In order to apply the global Cauchy theorem, it is desirable to have a reasonably efficient method of finding the index of a point with respect to a closed path. Here the concept of the winding number, which coincides with the index function for closed paths will help.

Let \(\gamma:[a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{C}\) be a closed path and \(z_{0} \notin \gamma^{*}\). Suppose that \(\theta_{z_{0}}\) is a continuous argument of \(\gamma-z_{0}\). We recall that the winding number of \(z_{0}\) with respect to \(\gamma\), is defined by \[\begin{aligned} W\left(\gamma, z_{0}\right)&=\frac{\theta_{z_{0}}(b)-\theta_{z_{0}}(a)}{2 \pi}. \end{aligned}\]

It was shown last time that \[\begin{aligned} W\left(\gamma, z_{0}\right)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma} \frac{1}{w-z_0} dw=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z_0). \end{aligned}\]

Remarks.

The winding number \(W\left(\gamma, z_{0}\right)\) computes precisely the number of times \(\gamma\) loops around \(z_0\). Since \(W\left(\gamma, z_{0}\right)\) is independent of the choice of continuous argument, we can analyze the change in argument of the quantity \(w-z_0\) as \(w\) travels along \(\gamma\).

Each time \(\gamma\) loops around \(z_0\) in an anticlockwise direction, then \(\frac{1}{2\pi} \arg(w - z_0)\) increases by \(1\). Conversely, if \(\gamma\) loops around \(z_0\) in a clockwise direction, then \(\frac{1}{2\pi} \arg(w - z_0)\) decreases by \(1\).

The last part of the global Cauchy theorem shows under what circumstances integration over one cycle can be replaced by integration over another, without changing the value of the integral.

Global Cauchy’s theorem, examples

Example 1

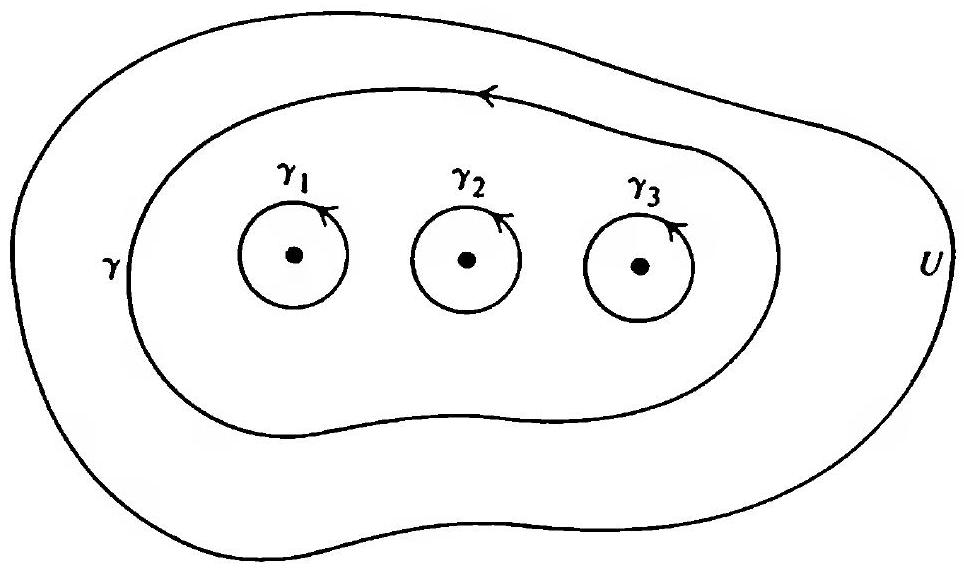

Let \(\gamma\) be a closed path, as below, in an open set \(U\subseteq \mathbb C\), and let \(f\) be holomorphic on \(U\).

In that figure, we see that \(\gamma\) winds around the three points \(z_{1}, z_{2}, z_{3}\), and winds once, hence \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z_1)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z_2)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z_3)=1\).

Let \(\gamma_{1}, \gamma_{2}, \gamma_{3}\) be small circles centered at \(z_{1}, z_{2}, z_{3}\) respectively, and oriented anticlockwise. Then we see that \[\int_{\gamma} f(z)dz=\int_{\gamma_{1}} f(z)dz+\int_{\gamma_{2}} f(z)dz+\int_{\gamma_{3}} f(z)dz.\]

Example 2

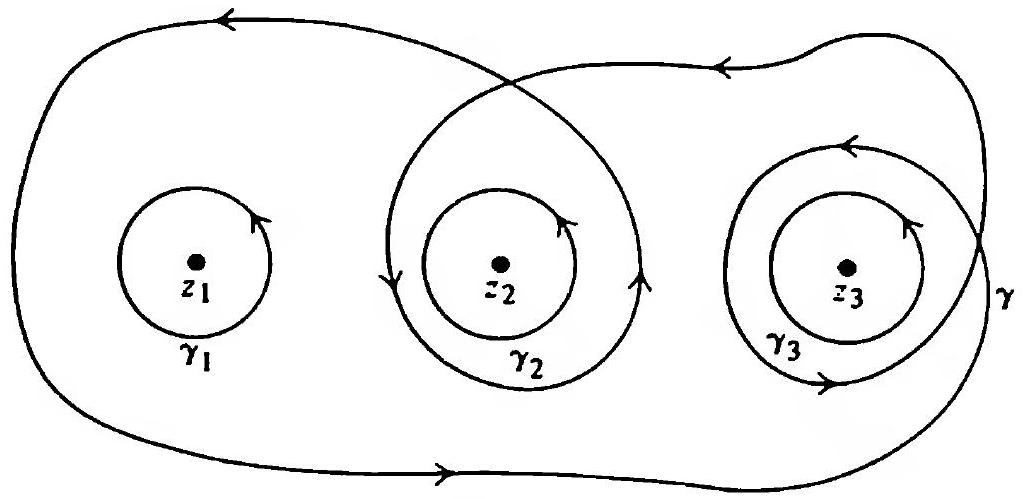

Let \(\gamma\) be the curve illustrated below, and let \(U\) be the plane from which three points \(z_{1}, z_{2}, z_{3}\) have been deleted. Let \(\gamma_{1}, \gamma_{2}, \gamma_{3}\) be small circles centered at \(z_{1}, z_{2}, z_{3}\) respectively, oriented counterclockwise.

Then \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z_1)=1\) and \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z_2)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z_3)=2\) and consequently \[\int_{\gamma} f(z)dz=\int_{\gamma_{1}} f(z)dz+2\int_{\gamma_{2}} f(z)dz+2\int_{\gamma_{3}} f(z)dz.\]

Example 3

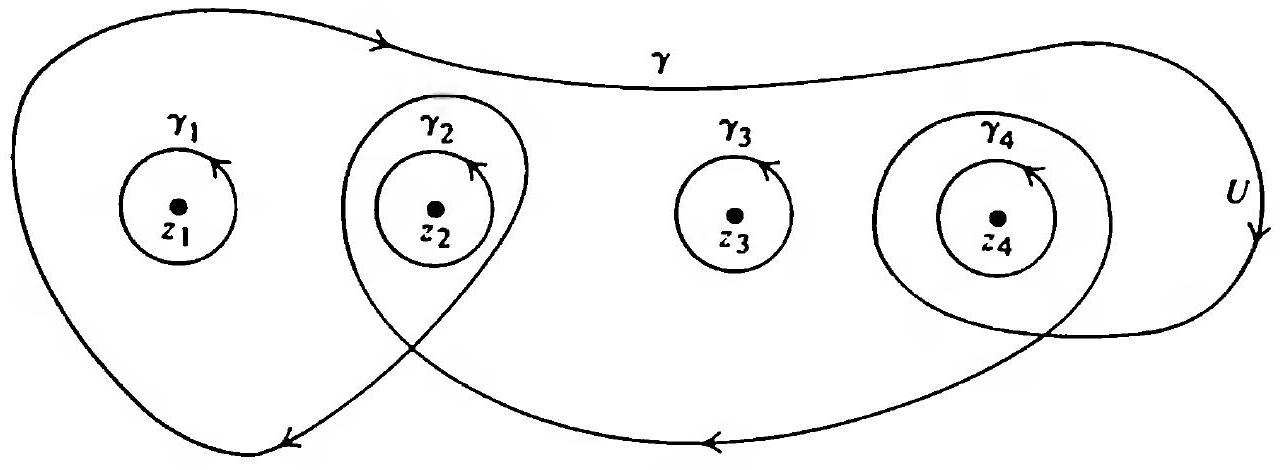

Let \(\gamma\) be the curve illustrated below, and let \(U\) be the plane from which four points \(z_{1}, z_{2}, z_{3}, z_4\) have been deleted. Let \(\gamma_{1}, \gamma_{2}, \gamma_{3}, \gamma_4\) be small circles centered at \(z_{1}, z_{2}, z_{3}, z_{4}\) respectively, oriented clockwise.

Then \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z_1)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z_3)=-1\) and \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z_2)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z_4)=-2\) and consequently \[\int_{\gamma} f(z)dz=-\int_{\gamma_{1}} f(z)dz-2\int_{\gamma_{2}} f(z)dz-\int_{\gamma_{3}} f(z)dz-2\int_{\gamma_{4}} f(z)dz.\]

Global Cauchy’s theorem, example

In the proof of Laurent series representation we used the following form of the Cauchy integral formula:

Let \(f\) be analytic on an open set \(\Omega\) containing the annulus \(\overline{A}\left(z_{0}, r_{1}, r_{2}\right)\) for \(0<r_{1}<r_{2}<\infty\), and let \(\gamma_{1}\) and \(\gamma_{2}\) denote the positively oriented inner and outer boundaries of the annulus. Then for \(z\in A\left(z_{0}, r_{1}, r_{2}\right)\), we have \[f(z)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma_{2}} \frac{f(w)}{w-z} d w-\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma_{1}} \frac{f(w)}{w-z} d w\]

Proof: The proof is a consequence of the global Cauchy theorem applied to the cycle \(\Gamma=\gamma_2-\gamma_1\), since \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=0 \quad \text{ for } \quad \alpha\not\in A\left(z_{0}, \rho_{1}, \rho_{2}\right),\] where \(0<\rho_1<r_1<r_2<\rho_2<\infty\) satisfy \(\overline{A}\left(z_{0}, \rho_{1}, \rho_{2}\right)\subset \Omega\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Homotopy and simply connected regions

Homotopy

Suppose \(\gamma_{0}\) and \(\gamma_{1}\) are closed curves in a topological space \(X\), both with parameter interval \(I=[0,1]\). We say that \(\gamma_{0}\) and \(\gamma_{1}\) are \(X\)-homotopic if there is a continuous mapping \(H\) of the unit square \(I \times I\) into \(X\) such that \[\begin{gathered} H(s, 0)=\gamma_{0}(s), \quad H(s, 1)=\gamma_{1}(s), \quad \text{ for all }\quad s\in I\\ H(0, t)=H(1, t), \quad \text{ for all }\quad t\in I. \end{gathered}\tag{*}\]

Put \(\gamma_{t}(s)=H(s, t)\). Then (*) defines a one-parameter family of closed curves \(\gamma_{t}\) in \(X\), which connects \(\gamma_{0}\) and \(\gamma_{1}\). Intuitively, this means that \(\gamma_{0}\) can be continuously deformed to \(\gamma_{1}\), within \(X\).

If \(\gamma_{0}\) is \(X\)-homotopic to a constant mapping \(\gamma_{1}\) (i.e., if \(\gamma_{1}^{*}\) consists of just one point), we say that \(\gamma_{0}\) is null-homotopic in \(X\).

Simply connected spaces

If \(X\) is connected and if every closed curve in \(X\) is null-homotopic, \(X\) is said to be simply connected.

Example Every convex region \(\Omega\) is simply connected. To see this, let \(\gamma_{0}\) be a closed curve in \(\Omega\), fix \(z_{1} \in \Omega\), and define \[H(s, t)=(1-t) \gamma_{0}(s)+t z_{1} \quad \text{ for all } \quad s, t\in[0, 1].\]

Let \(\gamma_{0}, \gamma_{1}:[0, 1]\to \mathbb C\) be closed paths. Let \(\alpha\in\mathbb C\), if \[\left|\gamma_{1}(s)-\gamma_{0}(s)\right|<\left|\alpha-\gamma_{0}(s)\right| \quad \text{ for all } \quad s\in I=[0, 1], \tag{X}\] then \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{1}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{0}}(\alpha)\).

Homotopic curves

Proof: First we derive from (X) that \(\alpha \notin \gamma_{0}^{*}\) and \(\alpha \notin \gamma_{1}^{*}\).

If \(\alpha \in \gamma_{0}^{*}\), then \(\alpha=\gamma_{0}(s)\) for some \(s\in I\) and then by (X), we obtain \[0\le \left|\gamma_{1}(s)-\gamma_{0}(s)\right|<\left|\gamma_{0}(s)-\gamma_{0}(s)\right|<0.\] This is a contradiction.

If \(\alpha \in \gamma_{1}^{*}\), then \(\alpha=\gamma_{1}(s)\) for some \(s\in I\) and by (X), we obtain \[\left|\gamma_{1}(s)-\gamma_{0}(s)\right|<\left|\gamma_{1}(s)-\gamma_{0}(s)\right|,\] which is again a contradiction.

Now, since \(\alpha \notin \gamma_{0}^{*}\), and \(\alpha \notin \gamma_{1}^{*}\), then \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{0}}(\alpha)\quad \text{ and } \quad \operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{1}}(\alpha)\] are defined.

We consider \[\gamma(s)=\frac{\gamma_{1}(s)-\alpha}{\gamma_{0}(s)-\alpha} \quad \text { for } \quad s\in I.\]

We see that \(\gamma\) is a curve since \(\alpha \notin \gamma_{0}^{*}\). Further, \(\gamma\) is a closed path since \(\gamma_{0}\) and \(\gamma_{1}\) are closed paths, and \[\gamma^{\prime}(s)=\frac{\left(\gamma_{0}(s)-\alpha\right) \gamma_{1}^{\prime}(s)-\left(\gamma_{1}(s)-\alpha\right) \gamma_{0}^{\prime}(s)}{\left(\gamma_{0}(s)-\alpha\right)^{2}}.\]

We have \[\gamma(s)-1=\frac{\gamma_{1}(s)-\alpha}{\gamma_{0}(s)-\alpha}-1=\frac{\gamma_{1}(s)-\gamma_{0}(s)}{\gamma_{0}(s)-\alpha} .\]

Therefore by (X) we deduce \[|\gamma(s)-1|<1 \quad \text { for } \quad s\in I.\]

Thus \(\gamma^{*} \subseteq D(1,1)\). Therefore \(0\) lies in the unbounded region determined by \(\gamma\) and hence \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(0)=0\) by the index theorem.

Now \[0=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(0)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma} \frac{d z}{z}=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{0}^{1} \frac{\gamma^{\prime}(s)}{\gamma(s)} d s\]

By the computations from the previous slide \[\begin{aligned} \frac{\gamma^{\prime}(s)}{\gamma(s)}&=\frac{\left(\gamma_{0}(s)-\alpha\right) \gamma_{1}^{\prime}(s)-\left(\gamma_{1}(s)-\alpha\right) \gamma_{0}^{\prime}(s)}{\left(\gamma_{0}(s)-\alpha\right)\left(\gamma_{1}(s)-\alpha\right)}\\ &=\frac{\gamma_{1}^{\prime}(s)}{\gamma_{1}(s)-\alpha}-\frac{\gamma_{0}^{\prime}(s)}{\gamma_{0}(s)-\alpha} . \end{aligned}\]

Therefore \[\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{0}^{1} \frac{\gamma_{1}^{\prime}(s)}{\gamma_{1}(s)-\alpha} d s=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{0}^{1} \frac{\gamma_{0}^{\prime}(s)}{\gamma_{0}(s)-\alpha} d s,\] and hence \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{0}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{1}}(\alpha). \qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

If \(\Gamma_{0}\) and \(\Gamma_{1}\) are \(\Omega\)-homotopic closed paths in a region \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\), and if \(\alpha \notin \Omega\), then \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{1}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{0}}(\alpha).\]

Proof: By definition, there is a continuous \(H: I^{2} \rightarrow \Omega\) such that \[\begin{gathered} H(s, 0)=\Gamma_{0}(s), \quad H(s, 1)=\Gamma_{1}(s),\quad \text{ for all }\quad s\in I,\\ \quad H(0, t)=H(1, t) \quad \text{ for all }\quad t\in I. \end{gathered}\]

Since \(I^{2}\) is compact, so is \(H\left(I^{2}\right)\). Moreover, \(\Omega^c\) is closed and \(\Omega\cap H\left(I^{2}\right)=\varnothing\). Hence there exists \(\varepsilon>0\) such that \[|\alpha-H(s, t)|>2 \varepsilon \quad \text { if } \quad(s, t) \in I^{2}.\]

Since \(H\) is uniformly continuous, there is \(n\in\mathbb N\) such that \[\left|H(s, t)-H\left(s^{\prime}, t^{\prime}\right)\right|<\varepsilon \quad \text { if } \quad\left|s-s^{\prime}\right|+\left|t-t^{\prime}\right| \leq 1 / n\]

Define polygonal closed paths \(\gamma_{0}, \ldots, \gamma_{n}\) by \[\gamma_{k}(s)=H\left(\frac{i}{n}, \frac{k}{n}\right)(n s+1-i)+H\left(\frac{i-1}{n}, \frac{k}{n}\right)(i-n s)\] if \(i-1 \leq n s \leq i\) (equivalently \(0\le i-ns\le 1\)), and \(i=1, \ldots, n\).

Combining the last two inequalities, we obtain \[\begin{aligned} \left|\gamma_{k}(s)-H(s, k / n)\right|\le & |H\left(i/n, k/n\right)-H(s, k / n)|(n s+1-i)\\ &+|H\left((i-1)/n, k/n\right)-H(s, k / n)|(i-n s)<\varepsilon \end{aligned}\] for \(k=0, \ldots, n\) and \(s\in I\).

In particular, taking \(k=0\) and \(k=n\), we obtain \[\left|\gamma_{0}(s)-\Gamma_{0}(s)\right|<\varepsilon, \quad \text{ and } \quad \left|\gamma_{n}(s)-\Gamma_{1}(s)\right|<\varepsilon.\]

By the fact that \(|\alpha-H(s, t)|>2 \varepsilon\) for all \((s, t) \in I^{2}\) and the last inequality from the previous slide \(|\gamma_{k}(s)-H(s, k / n)|<\varepsilon\) for \(s\in I\) and \(k=0, \ldots, n\), we obtain that \[\left|\alpha-\gamma_{k}(s)\right|>\varepsilon \quad \text{ for } \quad k=0, \ldots, n\quad \text{ and }\quad s\in I.\]

Observe also that \[\begin{aligned} |\gamma_{k-1}(s)&-\gamma_{k}(s)|\le |H\left(i/n, (k-1)/n\right)-H\left(i/n, k/n\right)|(n s+1-i)\\ &+|H\left((i-1)/n, (k-1)/n\right)-H((i-1)/n, k / n)|(i-n s)<\varepsilon \end{aligned}\] for \(k=0, \ldots, n\) and \(s\in I\).

Hence \[|\gamma_{k-1}(s)-\gamma_{k}(s)|< \left|\alpha-\gamma_{k}(s)\right|\] for \(k=0, \ldots, n\) and \(s\in I\).

Now by the previous lemma, observe that \[\begin{aligned} |\gamma_{n}(s)-\Gamma_{1}(s)|< \left|\alpha-\gamma_{n}(s)\right| \quad &\implies\quad \operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{n}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{1}}(\alpha),\\ |\gamma_{n-1}(s)-\gamma_{n}(s)|< \left|\alpha-\gamma_{n}(s)\right| \quad &\implies\quad \operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{n-1}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{n}}(\alpha),\\ &\quad \vdots\\ |\gamma_{0}(s)-\gamma_{1}(s)|< \left|\alpha-\gamma_{1}(s)\right| \quad &\implies\quad \operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{0}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{1}}(\alpha),\\ |\gamma_{0}(s)-\Gamma_{0}(s)|< \left|\alpha-\gamma_{0}(s)\right| \quad &\implies\quad \operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{0}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{0}}(\alpha). \end{aligned}\]

This proves that \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{1}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{0}}(\alpha)\] for every \(\alpha\in\Omega^c\) as desired.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Suppose that \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) is a simply connected region. Then for every closed curve \(\Gamma\) in \(\Omega\) we have \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=0 \quad \text{ whenever }\quad \alpha\not\in \Omega.\]

Proof: The region \(\Omega\) is simply connected, hence every closed curve \(\Gamma\) in \(\Omega\) is null-homotopic. In other words, there exists a continuous \(H: I^{2} \rightarrow \Omega\) such that \[\begin{gathered} H(s, 0)=\Gamma(s), \quad H(s, 1)=\gamma(s),\quad \text{ for all }\quad s\in I,\\ \quad H(0, t)=H(1, t) \quad \text{ for all }\quad t\in I, \end{gathered}\] where \(\gamma\) is a constant curve. Hence \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(\alpha)=0 \quad \text{ whenever }\quad \alpha\not\in \Omega.\] By the previous theorem we obtain that \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(\alpha)=0\) for \(\alpha\not\in \Omega\) as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remark.

The previous theorem shows that the global Cauchy theorem holds in simply connected regions \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\), since \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=0, \quad \text{ whenever }\quad \alpha\not\in \Omega\] for every closed path \(\Gamma\) in \(\Omega\).

The last but one theorem shows that if \(\Gamma_{0}\) and \(\Gamma_{1}\) are \(\Omega\)-homotopic closed paths in a region \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\), and if \(\alpha \notin \Omega\), then \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{1}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{0}}(\alpha),\] which combined with the second part of the global Cauchy theorem ensures that \[\int_{\Gamma_{0}} f(z) d z=\int_{\Gamma_{1}} f(z) d z.\]