6. Further applications of the Cauchy integral formula; Singular points and their classification PDF TEX

Applications of the Cauchy integral formula

Cauchy inequality

If \(f\) is holomorphic in an open set \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) that contains a closed disc \(\overline{D}(z_0, R)\) centered at \(z_{0}\) and of radius \(R\), then \[\big|f^{(n)}\left(z_{0}\right)\big| \leq \frac{n!\|f\|_{L^\infty(C)}}{R^{n}},\] where \(\|f\|_{L^\infty(C)}=\sup _{z \in C}|f(z)|\) denotes the supremum of \(|f|\) on the boundary circle \(C=\partial \overline{D}(z_0, R)\).

Liouville’s theorem and fundamental theorem of algebra

If \(f\) is entire and bounded, then \(f\) is constant.

Proof: Let \(B=\sup_{z\in\mathbb C}|f(z)|\). For each \(z_{0} \in \mathbb{C}\) and all \(R>0\), the Cauchy inequality yields \[\left|f^{\prime}\left(z_{0}\right)\right| \leq \frac{B}{R}\ _{\overrightarrow{R\to\infty}} \ 0.\] Thus \(f'(z_0)=0\) and hence \(f\) must be constant as \(\mathbb C\) is connected. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Every non-constant polynomial \[P(z)=a_{n} z^{n}+\cdots+a_1z+a_{0}\] with complex coefficients \(a_{n},\ldots, a_{0}\) has a root in \(\mathbb{C}\). In particular, if \(\operatorname{deg}P=n\ge 1\), then it has precisely \(n\) roots.

Fundamental theorem of algebra

Proof: If \(P\) has no roots, then \(1 / P(z)\) is a bounded holomorphic function.

To see this, we can of course assume that \(a_{n} \neq 0\), and write \[\frac{P(z)}{z^{n}}=a_{n}+\left(\frac{a_{n-1}}{z}+\cdots+\frac{a_{0}}{z^{n}}\right) \quad \text{ whenever } \quad z \neq 0.\]

Since each term in the parentheses goes to 0 as \(|z| \rightarrow \infty\) we conclude that there exists \(R>0\) so that if \(c=\left|a_{n}\right| / 2\), then \[|P(z)| \geq c|z|^{n} \quad \text { whenever }\quad |z|>R.\]

In particular, \(P\) is bounded from below when \(|z|>R\).

Since \(P\) is continuous and has no roots in the disc \(|z| \leq R\), it is bounded from below in that disc as well, thereby proving our claim.

By Liouville’s theorem we then conclude that \(1 / P\) is constant.

This contradicts our assumption that \(P\) is non-constant and proves the theorem. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Morera’s theorem — converse to the Cauchy theorem

Suppose \(f\) is a continuous complex function in an open set \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) such that \[\int_{\partial \Delta} f(z) d z=0\] for every closed triangle \(\Delta \subset \Omega\). Then \(f \in H(\Omega)\).

Proof: Let \(V\) be a convex open set in \(\Omega\).

As in the proof of Cauchy theorem for convex sets, we can construct a primitive \(F \in H(V)\) such that \(F^{\prime}=f\).

Fixing \(a\in V\) it suffices to take \[F(z)=\int_{[a, z]} f(\zeta) d \zeta \quad \text{ for }\quad z \in V.\]

Observe that \([a, z]\subseteq V\) since \(V\) is convex. Let \(z_{0} \in V\), then \[\begin{aligned} F(z)-F\left(z_{0}\right)&=\int_{[a, z]} f(\zeta) d \zeta-\int_{\left[a, z_{0}\right]} f(\zeta) d \zeta\\ &=\int_{\left[z_{0}, z\right]} f(\zeta) d \zeta. \end{aligned}\]

Hence, we obtain \[\frac{F(z)-F\left(z_{0}\right)}{z-z_{0}}-f\left(z_{0}\right)=\frac{1}{z-z_{0}} \int_{\left[z_{0}, z\right]}\left(f(\zeta)-f\left(z_{0}\right)\right) d \zeta,\] which implies

\[F'(z_0)=\lim_{z\to z_0}\frac{F(z)-F\left(z_{0}\right)}{z-z_{0}}=f\left(z_{0}\right).\]

Since derivatives of holomorphic functions are holomorphic, we have \(f \in H(V)\), for every convex open \(V \subseteq \Omega\), hence \(f \in H(\Omega)\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Sequences of holomorphic functions

A sequence \((f_{j})_{j\in\mathbb N}\) of functions in \(\Omega\) is said to converge to \(f\) uniformly on compact subsets of \(\Omega\) if to every compact \(K \subseteq \Omega\) and to every \(\varepsilon>0\) there is \(N=N(K, \varepsilon)\in\mathbb N\) such that \(\sup_{z\in K}|f_{j}(z)-f(z)|<\varepsilon\) if \(j>N\).

Let \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) be open. Suppose \((f_{j})_{j\in\mathbb N} \subseteq H(\Omega)\), and \(\lim_{j\to \infty}f_{j} = f\) uniformly on compact subsets of \(\Omega\). Then \(f \in H(\Omega)\), and \(\lim_{j\to \infty}f_{j}^{\prime} = f^{\prime}\) uniformly on compact subsets of \(\Omega\).

Proof: The function \(f\) is continuous, since the convergence is uniform on each compact disc in \(\Omega\). Let \(\Delta\) be a triangle in \(\Omega\). Then \(\Delta\) is compact, so

\[\int_{\partial \Delta} f(z) d z=\lim _{j \rightarrow \infty} \int_{\partial \Delta} f_{j}(z) d z=0\]

by Cauchy’s theorem. Hence Morera’s theorem implies that \(f \in H(\Omega)\).

Let \(K \subseteq \Omega\) be compact. There exists an \(r>0\) such that the union \(E\) of the closed discs \(\overline{D}(z ; r)\), for all \(z \in K\), is a compact subset of \(\Omega\).

Applying Cauchy’s inequality to \(f-f_{j}\), we have \[\left|f^{\prime}(z)-f_{j}^{\prime}(z)\right| \leq r^{-1}\left\|f-f_{j}\right\|_{L^{\infty}(E)} \quad\text{ for } \quad z \in K,\] where \(\|f\|_{L^\infty(E)}=\sup_{z\in E}|f(z)|\). Since \(\lim_{j\to \infty}f_{j} = f\) uniformly on \(E\), it follows that \(f_{j}^{\prime} \rightarrow f^{\prime}\) uniformly on \(K\).

Under the same hypothesis, \(\lim_{j\to \infty}f_{j}^{(n)} = f^{(n)}\) uniformly, on every compact set \(K \subseteq \Omega\), and for every positive integer \(n\in\mathbb N\).

Compare this with the situation on the real line, where sequences of infinitely differentiable functions can converge uniformly to nowhere differentiable functions!

Zero sets of holomorphic functions

Zero sets of holomorphic functions

Suppose that \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) is a region, and \(f \in H(\Omega)\), and \[Z(f)=\{a \in \Omega: f(a)=0\}.\]

Then either \(Z(f)=\Omega\), or

\(Z(f)\) has no limit point in \(\Omega\).

In the latter case there corresponds to each \(a \in Z(f)\) a unique positive integer \(m=m(a)\) such that \[f(z)=(z-a)^{m} g(z) \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in \Omega, \tag{*}\] where \(g \in H(\Omega)\) and \(g(a) \neq 0\). Furthermore, \(Z(f)\) is at most countable. The integer \(m\) is called the order of the zero which \(f\) has at the point \(a\).

Proof: Let \(A\) be the set of all limit points of \(Z(f)\) in \(\Omega\). In other words, \[A=\{z\in\mathbb C: \exists_{(z_n)_{n\in\mathbb N}\subseteq Z(f)} \ z_n\neq z\ \text{ and } \lim_{n\to \infty}z_n=z\}.\]

Since \(f\) is continuous, then \(A \subseteq Z(f)\). Indeed, if \(z\in A\) then there \((z_n)_{n\in\mathbb N}\subseteq Z(f)\) such that \(z_n\neq z\) and \(\lim_{n\to \infty}z_n=z\). By continuity of \(f\) we obtain that \(f(z)=\lim_{n\to \infty}f(z_n)=0\).

We will show that \(A\) is closed in \(\Omega\). Indeed, if \((z_n)_{n\in\mathbb N}\subseteq A\) and \(\lim_{n\to \infty}z_n=z_0\), then for any \(\varepsilon>0\) there exists \(N_{\varepsilon}\in\mathbb N\) such that \(z_n\in D(z_0, \varepsilon)\) for all \(n \ge N_{\varepsilon}\). Since \(z_n\) is a limit point of \(Z(f)\), then \(D(z_0, \varepsilon)\) contains infinitely many points of \(Z(f)\) different from \(z_n\), and hence infinitely many points of \(Z(f)\) different from \(z_0\). Thus \(z_0\in A\).

This shows that \(A\) is closed.

Fix \(a \in Z(f)\), and choose \(r>0\) so that \(D(a ; r) \subseteq \Omega\), then \[f(z)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} c_{n}(z-a)^{n} \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in D(a ; r).\]

There are now two possibilities:

Either \(c_{n}=0\) for all integers \(n\ge0\);

Or there is a smallest integer \(m\) (necessarily positive, since \(f(a)=0=c_0\)) such that \(c_{m} \neq 0\).

In that case, we can define \[g(z)= \begin{cases}(z-a)^{-m} f(z) & \text{ if } z \in \Omega\setminus\{a\}, \\ c_{m} & \text{ if } z=a. \end{cases}\]

It is clear that \(g \in H(\Omega\setminus\{a\})\).

Moreover, for \(z \in D(a ; r)\), we have \[f(z)=(z-a)^{m}g(z)=(z-a)^{m}\Big(c_m+\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} c_{n+m}(z-a)^{n}\Big),\tag{**}\] where \[g(z)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} c_{n+m}(z-a)^{n} \quad\text{ for } \quad z \in D(a ; r).\]

Since \(g \in H(D(a ; r))\), we consequently conclude that \(g \in H(\Omega)\).

Hence we obtain the factorization from (*) for some \(g \in H(\Omega)\), i.e. \[f(z)=(z-a)^{m} g(z) \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in \Omega.\]

Moreover, \(g(a)=c_m \neq 0\), and the continuity of \(g\) shows that there is a neighborhood of \(a\) in which \(g\) has no zero, by (**).

Thus we have shown that \(a\) is an isolated point of \(Z(f)\).

If \(a \in A\), and \(a\) is a limit point of \(Z(f)\) then the first case (i) must occur and all coefficients \(c_{n}\) are \(0\), then \(f(z)=0\) for all \(z \in D(a ; r)\), and consequently \(D(a ; r) \subseteq A\) and \(a\) is an interior point of \(A\).

This proves that \(A\) is open.

If \(B=\Omega\setminus A\), then \(B\) is open.

Thus \(\Omega\) is the union of the disjoint open sets \(A\) and \(B\).

Since \(\Omega\) is connected, we have

either \(A=\Omega\), in which case \(Z(f)=\Omega\),

or \(A=\varnothing\).

In the latter case, \(Z(f)\) has at most finitely many points in each compact subset of \(\Omega\), and since \(\Omega\) is \(\sigma\)-compact, \(Z(f)\) is at most countable. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Analytic continuations

Identity theorem

If \(f\) and \(g\) are holomorphic functions in a region \(\Omega\) and if \(f(z)=g(z)\) for all \(z\) in some set which has a limit point in \(\Omega\), then \[f(z)=g(z)\quad \text{ for all } \quad z \in \Omega.\]

Suppose we are given a pair of functions \(f\) and \(F\) analytic in regions \(\Omega\) and \(\Omega^{\prime}\), respectively, with \(\Omega \subseteq \Omega^{\prime}\). If the two functions agree on the smaller set \(\Omega\), we say that \(F\) is an analytic continuation of \(f\) into the region \(\Omega^{\prime}\).

The identity theorem then guarantees that there can be only one such analytic continuation, since \(F\) is uniquely determined by \(f\).

Symmetry principle

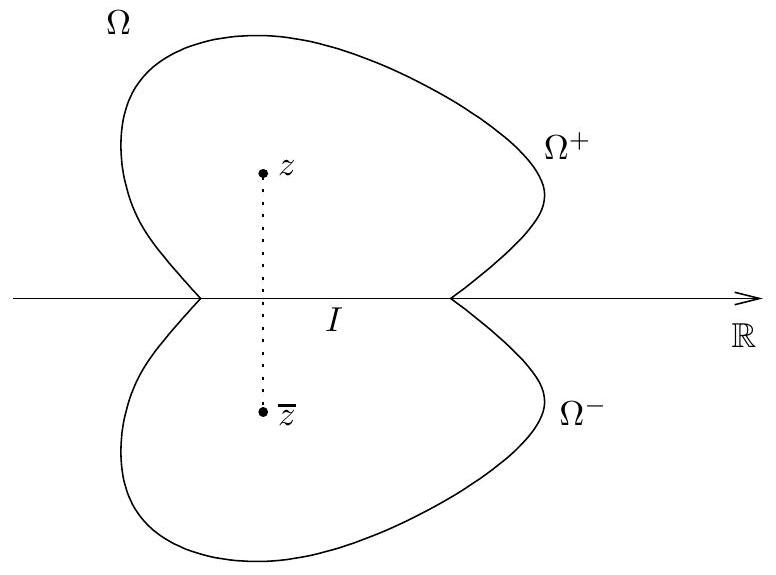

Let \(\Omega\) be an open subset of \(\mathbb{C}\) that is symmetric with respect to the real line, that is \[z \in \Omega \quad \text { if and only if } \quad \bar{z} \in \Omega .\]

Let \(\Omega^{+}\)denote the part of \(\Omega\) that lies in the upper half-plane and \(\Omega^{-}\) that part that lies in the lower half-plane.

Also, let \(I=\Omega \cap \mathbb{R}\) so that \(I\) denotes the interior of that part of the boundary of \(\Omega^{+}\)and \(\Omega^{-}\)that lies on the real axis. Then we have \[\Omega^{+} \cup I \cup \Omega^{-}=\Omega.\]

If \(f^{+}\)and \(f^{-}\)are holomorphic functions in \(\Omega^{+}\)and \(\Omega^{-}\)respectively, that extend continuously to \(I\) and \[f^{+}(x)=f^{-}(x) \quad \text { for all }\quad x \in I,\] then the function \(f\) defined on \(\Omega\) by \[f(z)= \begin{cases}f^{+}(z) & \text { if } z \in \Omega^{+}, \\ f^{+}(z)=f^{-}(z) & \text { if } z \in I, \\ f^{-}(z) & \text { if } z \in \Omega^{-}, \end{cases}\] is holomorphic on all of \(\Omega\).

Proof: One notes first that \(f\) is continuous throughout \(\Omega\). The only difficulty is to prove that \(f\) is holomorphic at points of \(I\). Suppose \(D\) is a disc centered at a point on \(I\) and entirely contained in \(\Omega\). We prove that \(f\) is holomorphic in \(D\) by Morera’s theorem.

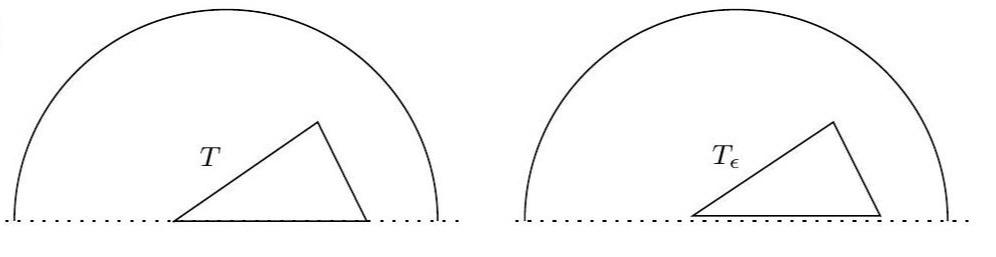

Suppose \(T\) is a triangle in \(D\). If \(T\) does not intersect \(I\), then \[\int_{T} f(z) d z=0,\] since \(f\) is holomorphic in the upper and lower half-discs.

Suppose now that one side or vertex of \(T\) is contained in \(I\), and the rest of \(T\) is in, say, the upper half-disc.

If \(T_{\epsilon}\) is the triangle obtained from \(T\) by slightly raising the edge or vertex which lies on \(I\), we have \(\int_{T_{\epsilon}} f(z) d z=0,\) since \(T_{\epsilon}\) is entirely contained in the upper half-disc. We then let \(\epsilon \rightarrow 0\), and by continuity we conclude that \[\int_{T} f(z) d z=0.\]

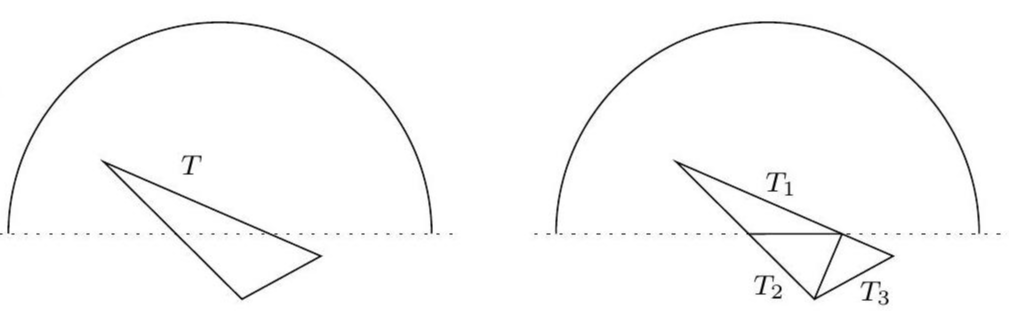

If the interior of \(T\) intersects \(I\), like below

we can reduce the situation to the previous one by writing \(T\) as the union of triangles each of which has an edge or vertex on \(I\). By Morera’s theorem \(f\) is holomorphic in \(D\), as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Schwarz reflection principle

Suppose that \(f\) is a holomorphic function in \(\Omega^{+}\)that extends continuously to \(I\) and such that \(f\) is real-valued on \(I\). Then there exists a function \(F\) holomorphic in all of \(\Omega\) such that \(F=f\) on \(\Omega^{+}\).

Proof. The idea is simply to define \(F(z)\) for \(z \in \Omega^{-}\)by \(F(z)=\overline{f(\overline{z})}\)

To prove that \(F\) is holomorphic in \(\Omega^{-}\)we note that if \(z, z_{0} \in \Omega^{-}\), then \(\overline{z}, \overline{z_{0}} \in \Omega^{+}\)and hence, the power series expansion of \(f\) near \(\overline{z_{0}}\) gives \[f(\overline{z})=\sum a_{n}\left(\overline{z}-\overline{z_{0}}\right)^{n}.\]

As a consequence we see that \(F\) is holomorphic in \(\Omega^{-}\), since \[F(z)=\sum \overline{a_{n}}\left(z-z_{0}\right)^{n}.\]

Since \(f\) is real valued on \(I\) we have \(\overline{f(x)}= f(x)\) whenever \(x \in I\) and hence \(F\) extends continuously up to \(I\).

The proof is complete once we invoke the symmetry principle. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Singularities

Riemann’s theorem on removable singularities

If \(a \in \Omega\) and \(f \in H(\Omega\setminus\{a\})\), then \(f\) is said to have an isolated singularity at the point \(a\).

If \(f\) can be so defined at \(a\) that the extended function is holomorphic in \(\Omega\), the singularity is said to be removable.

Suppose \(f \in H(\Omega\setminus\{a\})\) and \(f\) is bounded in \(D^{\prime}(a ; r)\), for some \(r>0\). Then \(f\) has a removable singularity at \(a\).

Proof: Define \[h(z)= \begin{cases} (z-a)^{2} f(z) & \text{ if } z\in \Omega\setminus\{a\},\\ 0 & \text{ if } z=a. \end{cases}\]

Our boundedness assumption shows that \[h^{\prime}(a)=\lim_{z\to a}\frac{h(z)-h(a)}{z-a}=\lim_{z\to a}(z-a) f(z)=0.\]

Since \(h\) is evidently differentiable at every other point of \(\Omega\), we have \(h \in H(\Omega)\). Moreover, \(h(a)=h'(a)=0\), so \[h(z)=\sum_{n=2}^{\infty} c_{n}(z-a)^{n} \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in D(a ; r).\]

We obtain the desired holomorphic extension of \(f\) by setting \(f(a)=c_{2}\), for then \[f(z)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} c_{n+2}(z-a)^{n} \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in D(a ; r). \qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Singularities

If \(a \in \Omega\) and \(f \in H(\Omega\setminus\{a\})\), then \(f\) has a singularity at \(a\), and one of the following three cases must occur:

f has a removable singularity at \(a\).

There are \(c_{1}, \ldots, c_{m}\in\mathbb C\) for some \(m\in\mathbb N\) and \(c_{m} \neq 0\), such that

\[f(z)-\sum_{k=1}^{m} \frac{c_{k}}{(z-a)^{k}}\]

has a removable singularity at \(a\).

If \(r>0\) and \(D(a ; r) \subseteq \Omega\), then \(f\left(D^{\prime}(a ; r)\right)\) is dense in \(\mathbb C\).

The conclusion of item (iii) is called the Casorati–Weierstrass theorem.

Remarks.

In case \((b), f\) is said to have a pole of order \(m\) at \(a\). The function

\[\sum_{k=1}^{m} c_{k}(z-a)^{-k}\]

a polynomial in \((z-a)^{-1}\), is called the principal part of \(f\) at \(a\).

It is clear in this situation that \(|f(z)| \rightarrow \infty\) as \(z \rightarrow a\).

In case (c), \(f\) is said to have an essential singularity at \(a\).

A statement equivalent to \((c)\) is that to each complex number \(w\in\mathbb C\) there corresponds a sequence \((z_{n})_{n\in\mathbb N}\) such that \(\lim_{n\to \infty}z_{n} = a\) and \[\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty}f\left(z_{n}\right) = w.\]

Proof: Suppose (c) fails.

Then there exist \(r>0\), and \(\delta>0\), and \(w\in\mathbb C\) such that \[|f(z)-w|>\delta\quad \text{ for all } \quad z\in D^{\prime}(a ; r).\]

Let us write \(D\) for \(D(a ; r)\) and \(D^{\prime}\) for \(D^{\prime}(a ; r)\). Define

\[g(z)=\frac{1}{f(z)-w} \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in D^{\prime}. \tag{1}\]

Then \(g \in H\left(D^{\prime}\right)\) and \(|g|<1 / \delta\). Since \(g\) is bounded, then by the previous theorem it extends to a holomorphic function in \(D\).

If \(g(a) \neq 0,\) then formula (1) shows that \(f\) is bounded in \(D^{\prime}(a ; \rho)\) for some \(\rho>0\).

Hence, by the previous theorem \(f\) can be extended to a holomorphic function in \(D(a ; \rho)\), and consequently holomorphic in \(\Omega\), yielding (a).

If \(g\) has a zero of order \(m \geq 1\) at \(a\), then we can write \[g(z)=(z-a)^{m} g_{1}(z) \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in D, \tag{2}\] where \(g_{1} \in H(D)\) and \(g_{1}(a) \neq 0\). Also, \(g_{1}\) has no zero in \(D^{\prime}\), by (1).

Thus we can set \(h=\) \(1 / g_{1}\) in \(D\).

Then \(h \in H(D)\), and \(h\) has no zero in \(D\), and we can write \[f(z)-w=(z-a)^{-m} h(z) \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in D^{\prime}. \tag{3}\]

But \(h\) has an expansion of the form \[h(z)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} b_{n}(z-a)^{n} \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in D, \tag{4}\] with \(b_{0} \neq 0\).

Identity (3) shows that (b) holds, with \(c_{k}=b_{m-k}\) for \(k=1, \ldots, m\).

This completes the proof.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remarks.

Suppose \(f\) has an isolated singularity at \(z_{0}\), and let \[\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} a_{n}\left(z-z_{0}\right)^{n}\] be the Laurent expansion of \(f\) about \(z_{0}\). Then one can see that

\(f\) has a removable singularity at \(z_{0}\) if \(a_{n}=0\) for all \(n<0\).

\(f\) has a pole of order \(m\) at \(z_{0}\) if \(m\) is the largest positive integer such that \(a_{-m} \neq 0\). (A pole of order \(1\) is called a simple pole.)

Finally, if \(a_{n} \neq 0\) for infinitely many \(n<0\), we say that \(f\) has an essential singularity at \(z_{0}\).

The behavior of a complex function \(f\) at \(\infty\) may be studied by considering \(g(z)= f(1 / z)\) for \(z\) near \(0\). Then we say that \(f\) has an isolated singularity at \(\infty\) if \(f\) is analytic on \(\{z\in \mathbb C:|z|>r\}\) for some \(r\); thus the function \(g(z)=f(1 / z)\) has an isolated singularity at \(0\). The type of singularity of \(f\) at \(\infty\) is then defined as that of \(g\) at \(0\).