10. Meromorphic functions and residues PDF TEX

Meromorphic functions

Meromorphic functions

A function \(f\) is said to be meromorphic in an open set \(\Omega\subseteq\mathbb C\) if there is a set \(A \subset \Omega\) such that

\(A\) has no limit point in \(\Omega\),

\(f \in H(\Omega\setminus A)\),

\(f\) has a pole at each point of \(A\).

Remarks.

Note that the possibility \(A=\varnothing\) is not excluded. Thus every \(f \in H(\Omega)\) is meromorphic in \(\Omega\).

Note also that (a) implies that no compact subset of \(\Omega\) contains infinitely many points of \(A\), and that \(A\) is therefore at most countable. Since every open set in \(\mathbb C\) is \(\sigma\)-compact.

Residues

Let \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) be open. If \(f\) is a meromorphic function in \(\Omega\) with the set of poles \(A\subset\Omega\). If \(a \in A\), and if \[Q(z)=\sum_{k=1}^{m} c_{k}(z-a)^{-k}, \tag{*}\] is the principal part of \(f\) at \(a\), (i.e., \(f-Q\) has a removable singularity at \(a\in A\)), then the number \(c_{1}\) is called the residue of \(f\) at \(a\), and we write \[c_{1}=\operatorname{Res}(f ; a). \tag{**}\]

If \(\Gamma\) is a cycle and \(a \notin \Gamma^{*}\), then by (*) and the global Cauchy theorem, we have \[\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} Q(z) d z=c_{1} \operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(a)=\operatorname{Res}(Q ; a) \operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(a). \tag{***}\]

Residue theorem

Suppose \(f\) is a meromorphic function in an open set \(\Omega\subseteq\mathbb C\). Let \(A\) be the set of points in \(\Omega\) at which \(f\) has poles. If \(\Gamma\) is a cycle in \(\Omega\setminus A\) such that \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=0 \quad \text { for all } \quad \alpha \notin \Omega, \tag{A}\] then \[\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} f(z) d z=\sum_{a \in A} \operatorname{Res}(f ; a) \operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(a). \tag{B}\]

Proof: Let \(B=\left\{a \in A: \operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(a) \neq 0\right\}\). Let \(W\) be the complement of \(\Gamma^{*}\).

Then \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(z)\) is constant in each component \(V\) of \(W\).

If \(V\) is unbounded, or if \(V\) intersects \(\Omega^{c}\), then (A) implies that \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(z)=0\) for every \(z \in V\). Since \(A\) has no limit point in \(\Omega\), we conclude that \(B\) is a finite set.

The sum in (B), though formally infinite, is therefore actually finite.

Let \(a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}\) be the points of \(B\), let \(Q_{1}, \ldots, Q_{n}\) be the principal parts of \(f\) at \(a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}\), and put \(g=f-\left(Q_{1}+\cdots+Q_{n}\right)\). (If \(B=\varnothing\), a possibility which is not excluded, then \(g=f\).)

Set \(\Omega_{0}=\Omega\setminus(A\setminus B)\). Since \(g\) has removable singularities at \(a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}\), the global Cauchy theorem applied to the function \(g\) and the open set \(\Omega_{0}\), shows that \[\int_{\Gamma} g(z) d z=0.\]

Hence \(f=g+\sum_{j=1}^nQ_j\) and \[\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} f(z) d z=\sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} Q_{k}(z) d z=\sum_{k=1}^{n} \operatorname{Res}\left(Q_{k} ; a_{k}\right) \operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}\left(a_{k}\right)\] and since \(f\) and \(Q_{k}\) have the same residue at \(a_{k}\), we obtain (B).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Applications of residues

Suppose \(\gamma\) is a closed path in a region \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\), such that \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(\alpha)=0\) for every \(\alpha\not\in\Omega\). Suppose also that \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(\alpha)=0\) or \(1\) for ever \(\alpha \in \Omega\setminus\gamma^{*}\), and let \(\Omega_{1}=\{\alpha\in\mathbb C:\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(\alpha)=1\}\). For any \(f \in H(\Omega)\) let \(N_{f}\) be the number of zeros of \(f\) in \(\Omega_{1}\), counted according to their multiplicities.

(Argument principle) If \(f\in H(\Omega)\) and \(f\) has no zeros on \(\gamma^{*}\) then \[N_{f}=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma} \frac{f^{\prime}(z)}{f(z)} d z=\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(0), \tag{A}\] where \(\Gamma=f \circ \gamma\).

(Rouché’s theorem) If also \(g \in H(\Omega)\) and \[|f(z)-g(z)|<|f(z)| \quad \text { for all } \quad z \in \gamma^{*}, \tag{B}\] then \(N_{g}=N_{f}\).

Remark.

Rouché’s theorem says that two holomorphic functions have the same number of zeros in \(\Omega_{1}\) if they are close together on the boundary of \(\Omega_{1}\), in the sense of condition (B).

Proof: Consider \(\varphi=f^{\prime} / f\), a meromorphic function in \(\Omega\).

If \(a \in \Omega\) and \(f\) has a zero of order \(m=m(a)\) at \(a\), then we have \(f(z)=(z-a)^{m} h(z)\), where \(h\) and \(1 / h\) are holomorphic in some neighborhood \(V\) of \(a\). In \(V\setminus\{a\}\), we have \[\varphi(z)=\frac{f^{\prime}(z)}{f(z)}=\frac{m}{z-a}+\frac{h^{\prime}(z)}{h(z)},\] since \(f'(z)=m(z-a)^{m-1}h(z)+(z-a)^{m}h'(z)\).

Thus \[\operatorname{Res}(\varphi ; a)=m(a).\]

Let \(A=\left\{a \in \Omega_{1}: f(a)=0\right\}\). If our assumptions about the index of \(\gamma\) are combined with the residue theorem one obtains \[\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma} \frac{f^{\prime}(z)}{f(z)} d z=\sum_{a \in A} \operatorname{Res}(\varphi ; a)=\sum_{a \in A} m(a)=N_{f}.\]

This proves one half of (A). The other half is a matter of direct computation:

\[\begin{aligned} \operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(0) & =\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} \frac{d z}{z}=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{0}^{2 \pi} \frac{\Gamma^{\prime}(s)}{\Gamma(s)} d s \\ & =\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{0}^{2 \pi} \frac{f^{\prime}(\gamma(s))}{f(\gamma(s))} \gamma^{\prime}(s) d s=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma} \frac{f^{\prime}(z)}{f(z)} d z=N_f \end{aligned}\] The parameter interval of \(\gamma\) was here taken to be \([0,2 \pi]\).

In order to prove the Rouché theorem recall the following lemma:

Lemma.Let \(\gamma_{0}, \gamma_{1}:[0, 1]\to \mathbb C\) be closed paths. Let \(\alpha\in\mathbb C\), if \[\left|\gamma_{1}(s)-\gamma_{0}(s)\right|<\left|\alpha-\gamma_{0}(s)\right| \quad \text{ for all } \quad s\in I=[0, 1],\] then \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{1}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma_{0}}(\alpha)\).

Condition (B) shows that \(g\) has no zero on \(\gamma^{*}\). Hence (A) holds with \(g\) in place of \(f\). Put \(\Gamma_{0}=g \circ \gamma\). Then it follows from (B) that \[|\Gamma(t)-\Gamma_0(t)|<|\Gamma(t)| \quad \text{ for all } \quad t\in[0, 1].\]

Then by the previous lemma with \(\alpha=0\) and (A), we obtain \[N_{g}=\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{0}}(0)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(0)=N_{f}. \qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Example

Determine the numbers of zeros of \[z^{87}+36 z^{57}+71 z^{4}+z^{3}-z+1\] inside \(|z|=1\).

Solution: Take \(g(z)=z^{87}+36 z^{57}+71 z^{4}+z^{3}-z+1\), and \(f(z)=71 z^{4}\).

Then for \(|z|=1\), we have \[\begin{aligned} |f(z)-g(z)|&=\left|z^{87}+36 z^{57}+z^{3}-z+1\right|\\ &\leq 1+36+1+1+1<71=|f(z)|. \end{aligned}\]

Hence, by Rouché’s theorem with \(\Omega=\mathbb{C}\) and \(\Omega_{1}=D(0,1)\) and \(\gamma=e^{it}\) for \(t\in[0, 2\pi]\) we conclude that \(g(z)\) has four zeros inside \(\partial D(0,1)\) counted according to multiplicity.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

We will prove that \[\lim _{A \rightarrow \infty} \int_{-A}^{A} \frac{\sin x}{x} e^{i t x} d x = \begin{cases}\pi & \text { if } |t|<1, \tag{*}\\ 0 & \text { if }|t|>1. \end{cases}\] The limit in (*) is \(\pi / 2\) when \(t= \pm 1\).

Proof: Since the function \[\frac{\sin z}{z} e^{i t z}\] is entire, its integral over \([-A, A]\) equals that over the path \(\Gamma_{A}\) obtained by going from \(-A\) to \(-1\) along the real axis, from \(-1\) to \(1\) along the lower half of the unit circle, and from \(1\) to \(A\) along the real axis. This follows from Cauchy’s theorem.

\(\Gamma_{A}\) avoids the origin, and we may therefore use the identity \[2 i \sin z=e^{i z}-e^{-i z}\] to see that \[\int_{\Gamma_A}\frac{\sin z}{z} e^{i t z}dz=\varphi_{A}(t+1)-\varphi_{A}(t-1), \tag{**}\] where \[\frac{1}{\pi} \varphi_{A}(s)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma_{A}} \frac{e^{i s z}}{z} d z.\]

We now complete \(\Gamma_{A}\) to a closed path in two ways:

First, by the semicircle from \(A\) to \(-A i\) to \(-A\);

Secondly, by the semicircle from \(A\) to \(A i\) to \(-A\).

The function \(e^{i s z} / z\) has a single pole, at \(z=0\), where its residue is \(1\).

Integrating over the closed path contained in the lower half plane, it follows that \[\frac{1}{\pi} \varphi_{A}(s)=\frac{1}{2 \pi} \int_{-\pi}^{0} \exp \left(i s A e^{i \theta}\right) d \theta. \tag{L}\]

Integrating over the closed path contained in the upper half plane, it follows that \[\frac{1}{\pi} \varphi_{A}(s)=1-\frac{1}{2 \pi} \int_{0}^{\pi} \exp \left(i s A e^{i \theta}\right) d \theta. \tag{U}\]

Note that

\[\left|\exp \left(i s A e^{i \theta}\right)\right|=\exp (-A s \sin \theta) \tag{5}\]

and that this is \(<1\) and tends to 0 as \(A \rightarrow \infty\) if \(s\) and \(\sin \theta\) have the same sign.

The dominated convergence theorem shows therefore that the integral in (L) tends to \(0\) if \(s<0\), and the one in (U) tends to \(0\) if \(s>0\).

Thus \[\lim _{A \rightarrow \infty} \varphi_{A}(s)= \begin{cases} \pi & \text { if } s>0 \\ 0 & \text { if } s<0. \end{cases}\]

If we use (**) and apply this bound to \(s=t+1\) and to \(s=t-1\), we obtain (*), i.e. \[\lim _{A \rightarrow \infty} \int_{-A}^{A} \frac{\sin x}{x} e^{i t x} d x= \begin{cases}\pi & \text { if } |t|<1, \\ 0 & \text { if }|t|>1.\end{cases}\]

Since \(\varphi_{A}(0)=\pi / 2\), the limit above is \(\pi / 2\) when \(t= \pm 1\).

Note that (*) gives the Fourier transform of \((\sin x) / x\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

We prove that \[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{d x}{1+x^{2}}=\pi\] by using contour integration.

Proof: Clearly \(1 /\left(1+x^{2}\right)\) is the derivative of \(\arctan x\) and the conclusion readily follows. However, this is a good example to illustrate the residue calculus. So we provide a residue calculation that leads to another proof.

Consider the function \[f(z)=\frac{1}{1+z^{2}},\] which is holomorphic in the complex plane except for simple poles at the points \(i\) and \(-i\).

We choose the contour \(\gamma_{R}\) as below. The contour consists of the segment \([-R, R]\) on the real axis and of a large half-circle centered at the origin in the upper half-plane.

Since we may write \[f(z)=\frac{1}{(z-i)(z+i)}=\frac{1}{2i(z-i)}-\frac{1}{2i(z+i)},\]

we see that the residue of \(f\) at \(i\) is simply \(1 / 2 i\).

Therefore, if \(R\) is large enough, we have \[\int_{\gamma_{R}} f(z) d z=\frac{2 \pi i}{2 i}=\pi.\]

If we denote by \(C_{R}^{+}\) the large half-circle of radius \(R\), we see that \[\left|\int_{C_{R}^{+}} f(z) d z\right| \leq \pi R \frac{B}{R^{2}} \leq \frac{M}{R},\] where we have used the fact that \(|f(z)| \leq B /|z|^{2}\) when \(z \in C_{R}^{+}\) and \(R\) is large. So this integral goes to \(0\) as \(R \rightarrow \infty\).

Therefore, in the limit we find that \[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x) d x=\pi\] as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

We prove that \[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{e^{a x}}{1+e^{x}} d x=\frac{\pi}{\sin \pi a}, \quad \text{ with } \quad 0<a<1.\]

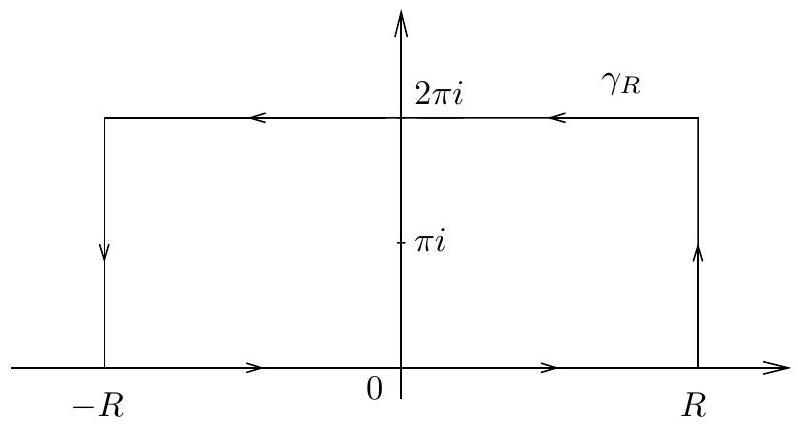

Proof: To prove this formula, let \(f(z)=e^{a z} /\left(1+e^{z}\right)\), and consider the contour consisting of a rectangle in the upper half-plane with a side lying

on the real axis, and a parallel side on the \(\operatorname{line} \operatorname{Im}(z)=2 \pi\).

The only point in the rectangle \(\gamma_{R}\) where the denominator of \(f\) vanishes is \(z=\pi i\).

To compute the residue of \(f\) at that point, we argue as follows: \[(z-\pi i) f(z)=e^{a z} \frac{z-\pi i}{1+e^{z}}=e^{a z} \frac{z-\pi i}{e^{z}-e^{\pi i}}\]

On the right the inverse of a difference quotient, and in fact \[\lim _{z \rightarrow \pi i} \frac{e^{z}-e^{\pi i}}{z-\pi i}=e^{\pi i}=-1\] since \(e^{z}\) is its own derivative.

Therefore, the function \(f\) has a simple pole at \(\pi i\) with residue \[\operatorname{Res}(f; \pi i)=-e^{a \pi i}.\]

As a consequence, the residue formula says that \[\int_{\gamma_{R}} f=-2 \pi i e^{a \pi i}.\]

We now investigate the integrals of \(f\) over each side of the rectangle.

Let \(I_{R}\) denote \[\int_{-R}^{R} f(x) d x,\] and \(I\) the integral we wish to compute, so that \(I_{R} \rightarrow I\) as \(R \rightarrow \infty\).

Then, it is clear that the integral of \(f\) over the top side of the rectangle (with the orientation from right to left) is \[-e^{2 \pi i a} I_{R}.\]

Finally, if \(A_{R}=\{R+i t: 0 \leq t \leq 2 \pi\}\) denotes the vertical side on the right, then \[\left|\int_{A_{R}} f\right| \leq \int_{0}^{2 \pi}\left|\frac{e^{a(R+i t)}}{1+e^{R+i t}}\right| d t \leq C e^{(a-1) R}\] and since \(a<1\), this integral tends to \(0\) as \(R \rightarrow \infty\).

Similarly, the integral over the vertical segment on the left goes to \(0\), since it can be bounded by \(C e^{-a R}\) and \(a>0\). Therefore, we obtain \[I-e^{2 \pi i a} I=\lim_{R\to\infty}\int_{\gamma_{R}} f=-2 \pi i e^{a \pi i}\] from which we deduce \[\begin{aligned} I & =-2 \pi i \frac{e^{a \pi i}}{1-e^{2 \pi i a}} =\frac{2 \pi i}{e^{\pi i a}-e^{-\pi i a}} =\frac{\pi}{\sin \pi a} \end{aligned}\] and the computation is complete. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Now we calculate another Fourier transform, namely \[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{e^{-2 \pi i x \xi}}{\cosh \pi x} d x=\frac{1}{\cosh \pi \xi}\] where \[\cosh z=\frac{e^{z}+e^{-z}}{2}.\]

Proof: In other words, the function \(1 / \cosh \pi x\) is its own Fourier transform, a property also shared by \(e^{-\pi x^{2}}\). To see this, we use a rectangle \(\gamma_{R}\) as below whose width goes to infinity, but whose height is fixed.

For a fixed \(\xi \in \mathbb{R}\), let \[f(z)=\frac{e^{-2 \pi i z \xi}}{\cosh \pi z}.\]

Note that the denominator of \(f\) vanishes precisely when \(e^{\pi z}=-e^{-\pi z}\), that is, when \(e^{2 \pi z}=-1\).

In other words, the only poles of \(f\) inside the rectangle are at the points \(\alpha=i / 2\) and \(\beta=3 i / 2\).

To find the residue of \(f\) at \(\alpha=i/2\), we note that \[\begin{aligned} (z-\alpha) f(z) & =e^{-2 \pi i z \xi} \frac{2(z-\alpha)}{e^{\pi z}+e^{-\pi z}} \\ & =2 e^{-2 \pi i z \xi} e^{\pi z} \frac{(z-\alpha)}{e^{2 \pi z}-e^{2 \pi \alpha}} \end{aligned}\]

We recognize on the right the reciprocal of the difference quotient for the function \(e^{2 \pi z}\) at \(z=\alpha\). Therefore \[\lim _{z \rightarrow \alpha}(z-\alpha) f(z)=2 e^{-2 \pi i \alpha \xi} e^{\pi \alpha} \frac{1}{2 \pi e^{2 \pi \alpha}}=\frac{e^{\pi \xi}}{\pi i},\] which shows that \(f\) has a simple pole at \(\alpha\) with residue \(e^{\pi \xi} /(\pi i)\).

Similarly, we find that \(f\) has a simple pole at \(\beta\) with residue \(-e^{3 \pi \xi} /(\pi i)\).

We dispense with the integrals of \(f\) on the vertical sides by showing that they go to zero as \(R\) tends to infinity.

Indeed, if \(z=R+i y\) with \(0 \leq y \leq 2\), then \[\left|e^{-2 \pi i z \xi}\right| \leq e^{4 \pi|\xi|},\] and \[\begin{aligned} |\cosh \pi z| & =\left|\frac{e^{\pi z}+e^{-\pi z}}{2}\right| \\ & \geq \frac{1}{2}| | e^{\pi z}\left|-\left|e^{-\pi z}\right|\right| \\ & \geq \frac{1}{2}\left(e^{\pi R}-e^{-\pi R}\right) \rightarrow \infty \quad \text { as } \quad R \rightarrow \infty. \end{aligned}\]

This shows that the integral over the vertical segment on the right goes to 0 as \(R \rightarrow \infty\). A similar argument shows that the integral of \(f\) over the vertical segment on the left also goes to 0 as \(R \rightarrow \infty\).

Finally, we see that if \(I\) denotes the integral we wish to calculate, then the integral of \(f\) over the top side of the rectangle (with the orientation from right to left) is simply \(-e^{4 \pi \xi} I\), where we have used the fact that \(\cosh \pi \zeta\) is periodic with period \(2 i\).

In the limit as \(R\) tends to infinity, the residue formula gives

\[\begin{aligned} I-e^{4 \pi \xi} I & =2 \pi i\left(\frac{e^{\pi \xi}}{\pi i}-\frac{e^{3 \pi \xi}}{\pi i}\right) =-2 e^{2 \pi \xi}\left(e^{\pi \xi}-e^{-\pi \xi}\right) \end{aligned}\] and since \(1-e^{4 \pi \xi}=-e^{2 \pi \xi}\left(e^{2 \pi \xi}-e^{-2 \pi \xi}\right)\), we find that \[\begin{aligned} I&=2 \frac{e^{\pi \xi}-e^{-\pi \xi}}{e^{2 \pi \xi}-e^{-2 \pi \xi}}=2 \frac{e^{\pi \xi}-e^{-\pi \xi}}{\left(e^{\pi \xi}-e^{-\pi \xi}\right)\left(e^{\pi \xi}+e^{-\pi \xi}\right)}\\ &=\frac{2}{e^{\pi \xi}+e^{-\pi \xi}}=\frac{1}{\cosh \pi \xi} \end{aligned}\] as claimed.

Remark.

A similar argument actually establishes the following formula: \[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-2 \pi i x \xi} \frac{\sin \pi a}{\cosh \pi x+\cos \pi a} d x=\frac{2 \sinh 2 \pi a \xi}{\sinh 2 \pi \xi}\] whenever \(0<a<1\), and where \(\sinh z=\left(e^{z}-e^{-z}\right) / 2\).

We have proved above the particular case \(a=1 / 2\).