4. Index function; Cauchy theorem PDF TEX

Index function

Index function

For \(a \in \mathbb{C}\) and \(a \notin \gamma^{*}\), we write \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(a)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma} \frac{d z}{z-a} d z\] and \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(a)\) is called the index of \(a\) with respect to \(\gamma\). This is also called the winding number of \(a\) with respect to \(\gamma\).

For a closed path \(\gamma\) and \(\Omega=\mathbb{C} \backslash \gamma^{*}\), we have \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(a) \in \mathbb{Z} \quad \text { for } \quad a \in \Omega.\]

Further \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(a)\) is constant on each region of \(\Omega\) determined by \(\gamma\) and it is equal to zero on the unbounded region of \(\Omega\) determined by \(\gamma\).

Proof: By definition \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(a)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma} \frac{1}{z-a} d z =\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\alpha}^{\beta} \frac{\gamma^{\prime}(t)}{\gamma(t)-a} d t\] where \(\gamma:[\alpha, \beta]\to\mathbb C\) is a closed path so that \(\gamma(t) \neq a\) for \(t\in [\alpha, \beta]\).

We consider \[h(t)=\int_{\alpha}^{t} \frac{\gamma^{\prime}(t)}{\gamma(t)-a} d t.\]

We prove that \(h(\beta)\) is a multiple of \(2 \pi i\) and this implies \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(a)\in\mathbb Z\).

Since \(\gamma(t)\) is piecewise continuously differentiable, the integral on the right exists for \(t\in [\alpha, \beta]\). Further \(h(t)\) is continuous on \([\alpha, \beta]\) and \[h^{\prime}(t)=\frac{\gamma^{\prime}(t)}{\gamma(t)-a}\] for all but finitely many \(t \in[\alpha, \beta]\).

Now we observe that the derivative of \(e^{-h(t)}(\gamma(t)- a)\) vanishes for all but finitely many \(t \in[\alpha, \beta]\).

This implies that \(e^{-h(t)}(\gamma(t)-a)=c\in \mathbb C\) for \(t\in [\alpha, \beta]\), where \(c\) is a constant, since the function on the left is continuous in \([\alpha, \beta]\).

By putting \(t=\alpha\) and \(t=\beta\), we have \[e^{-h(\alpha)}(\gamma(\alpha)-a)=e^{-h(\beta)}(\gamma(\beta)-a),\] which implies \(e^{h(\beta)}=1\), since \(\gamma(\alpha)=\gamma(\beta)\), \(a \notin \gamma^{*}\) and \(h(\alpha)=0\).

Thus the function \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z)\) is integer valued on \(\Omega\) and continuous.

Therefore for any component \(C\) of \(\Omega\), we see that \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(C)\) is a connected set of integers and hence it consists of a single element.

Next we take \(z\) in the unbounded region such that \(\frac{|z|}{2} \geq|a|\) and \(|z|>\frac{\ell(\gamma)}{\pi}\). Then \(|z-a| \geq|z|-|a| \geq \frac{|z|}{2}\) and \[\left|\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z)\right| \leq \frac{1}{2 \pi} \frac{2}{|z|} \ell(\gamma)<1 .\]

This implies \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z)=0\) on the unbounded region, since \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z)\in\mathbb Z\) and constant on the unbounded region as already proved. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remarks.

If \(\gamma\) is a closed curve in \(\mathbb C\) and \(a\) is a point not lying on \(\gamma^*\), then we may calculate the number of times the curve \(\gamma\) winds around \(a\) by looking at the change of argument of the quantity \(z-a\) as \(z\) travels on \(\gamma^*\). Every time \(\gamma^*\) loops around \(a\), the quantity \((1/2\pi) \arg(z-a)\) increases (or decreases) by \(1\).

When we define a complex logarithm function we will be able to explain geometrically that \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(a)\) represents the number of times the curve \(\gamma\) wraps around \(a\). That is why it is also called the winding number of \(\gamma\) around \(a\).

Index for positively oriented circles

If \(\gamma\) is the positively oriented circle with center at \(a\) and radius \(r\), then \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z)= \begin{cases} 1, & \text{ if } |z-a| < r, \\ 0, & \text{ if } |z-a| > r. \end{cases}\]

Proof: Let \[\gamma(t):=a+r e^{i t}, \quad0 \leq t \leq 2 \pi,\] By the previous theorem it is enough to compute \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(a)\), then \[\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma} \frac{d z}{z-a} = \frac{r}{2 \pi} \int_{0}^{2 \pi} \left( r e^{i t} \right)^{-1} e^{i t} d t = 1. \quad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Primitive functions

Suppose that \(f:\Omega\to\mathbb C\) is a function on the open set \(\Omega\). A primitive for \(f\) on \(\Omega\) is a function \(F\) that is holomorphic on \(\Omega\) and such that \[F^{\prime}(z)=f(z) \quad \text{ for all } \quad z \in \Omega.\]

If a continuous function \(f:\Omega\to \mathbb C\) has a primitive \(F\) in \(\Omega\), and \(\gamma\) is a curve in \(\Omega\) that begins at \(w_{1}\) and ends at \(w_{2}\), then \[\int_{\gamma} f(z) d z=F\left(w_{2}\right)-F\left(w_{1}\right).\]

Proof: If \(\gamma\) is a continuously differentiable curve, the proof is a simple application of the chain rule and the fundamental theorem of calculus.

Indeed, if \(z(t):[a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{C}\) is a parametrization for \(\gamma\), then \(z(a)=w_{1}\) and \(z(b)=w_{2}\), and we have \[\begin{aligned} \int_{\gamma} f(z) d z & =\int_{a}^{b} f(z(t)) z^{\prime}(t) d t \\ & =\int_{a}^{b} F^{\prime}(z(t)) z^{\prime}(t) d t \\ & =\int_{a}^{b} \frac{d}{d t} F(z(t)) d t =F(z(b))-F(z(a)). \end{aligned}\]

If \(\gamma\) is only a piecewise continuously differentiable curve, then it can be expressed in the form \(\gamma = \gamma_1 + \ldots + \gamma_k\), where each \(\gamma_j\) is a continuously differentiable curve. We can then apply the previous result to each \(\gamma_j\), and we are done.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

If \(\gamma\) is a closed curve in an open set \(\Omega\), and \(f:\Omega\to\mathbb C\) is continuous and has a primitive in \(\Omega\), then \[\int_{\gamma} f(z) d z=0.\]

Proof: This is evident since the endpoints of a closed curve coincide.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Example The function \(f(z)=1 / z\) does not have a primitive in the open set \(\mathbb{C}\setminus\{0\}\), since if \(C\) is the unit circle parametrized by \(z(t)=e^{i t}\), with \(0 \leq t \leq 2 \pi\), we have \[\int_{C} f(z) d z=\int_{0}^{2 \pi} \frac{i e^{i t}}{e^{i t}} d t=2 \pi i \neq 0.\]

If \(f\) is holomorphic in a region \(\Omega\) and \(f^{\prime}=0\), then \(f\) is constant.

Proof: Fix a point \(w_{0} \in \Omega\).

It suffices to show that \(f(w)=f\left(w_{0}\right)\) for all \(w \in \Omega\).

Since \(\Omega\) is connected, for any \(w \in \Omega\), there exists a curve \(\gamma\) which joins \(w_{0}\) to \(w\). Since \(f\) is clearly a primitive for \(f^{\prime}\), we have \[\int_{\gamma} f^{\prime}(z) d z=f(w)-f\left(w_{0}\right).\]

By assumption, \(f^{\prime}=0\) so the integral on the left is 0 , and we conclude that \(f(w)=f\left(w_{0}\right)\) as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Local Cauchy theorem

Cauchy–Goursat theorem

Let \(\Omega\subseteq\mathbb C\) be open and let \(\triangle\) be a closed triangle in \(\Omega\) and \(p \in \Omega\). Let \(f\) be continuous in \(\Omega\) and holomorphic in \(\Omega \backslash\{p\}\). Then \[\int_{\partial \triangle} f(z) d z=0,\] where \(\partial \triangle\) denotes the boundary of \(\triangle\).

Remark. This theorem implies that \[\int_{\gamma} f(z) d z=0\] for all triangular paths in an open set \(\Omega\) whenever \(f \in H(\Omega)\). Hence, we say that the Cauchy theorem is valid for all triangular paths in \(\Omega\).

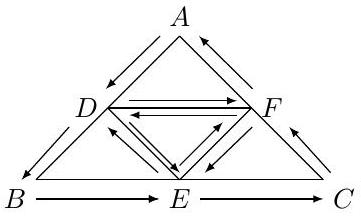

Proof: Let \(\triangle=\triangle(A, B, C)\) be a triangle in \(\Omega\) with vertices \(A, B\) and \(C\).

Put \(J=\int_{\partial \triangle} f(z) d z\).

Let \(L\) be the length of \(\partial \triangle\) and write \(\triangle_{0}=\triangle\).

Let \(D, E, F\) be the midpoints of \([A, B]\), \([B, C]\) and \([C, A]\), respectively, and consider the four triangles arising from joining these midpoints: \[\begin{aligned} \triangle_{01}=\triangle(A,D,F),\quad \triangle_{02}&=\triangle(D, B, E), \quad \triangle_{03}=\triangle(F, E, C)\\ \triangle_{04}&=\triangle(E, F, D). \end{aligned}\]

Then \[J=\int_{\partial \triangle} f(z) d z=\sum_{i=1}^{4} \int_{\partial \triangle_{0 i}} f(z) d z\] and the length of \(\partial \triangle_{0i}\) is equal to \(2^{-1} L\) for \(1 \leq i \leq 4\).

\(\triangle_0=\triangle(A, B, C),\)

\[\begin{aligned} \triangle_{01}=\triangle(A,D,F),\quad \triangle_{02}&=\triangle(D, B, E), \quad \triangle_{03}=\triangle(F, E, C)\\ \triangle_{04}&=\triangle(E, F, D). \end{aligned}\]

By the pigeonhole principle there exists \(i_{0}\) with \(1 \leq i_{0} \leq 4\) such that \[\left|\int_{\partial \triangle_{i_{0}}} f(z) d z\right| \geq 4^{-1}|J| .\] Then set \(\triangle_{1}=\triangle_{0 i_{0}}\).

Proceeding similarly, we obtain a sequence of triangles \[\triangle \supset \triangle_{1} \supset \ldots \supset \triangle_{n} \supset \ldots\] such that \[\left|\int_{\partial \triangle_{n}} f(z) d z\right| \geq 4^{-n}|J| \quad \text { for } \quad n \geq 0,\] and the length of \(\partial \triangle_{n}\) is equal to \(2^{-n} L\).

By the compactness we have \[\bigcap_{n\ge 0}\triangle_n\neq\varnothing.\]

Therefore, there exists \(z_{0}\) such that \(z_{0} \in \triangle_{n}\) for every \(n \geq 0\).

First, we consider the case \(p \notin \triangle\).

We observe that \(f(z)\) is holomorphic at \(z_{0}\) since \(p \neq z_{0}\). Then for \(\varepsilon>0\) there exists \(\delta>0\) depending only on \(\varepsilon\) such that \[\left|f(z)-f\left(z_{0}\right)-f^{\prime}\left(z_{0}\right)\left(z-z_{0}\right)\right|<\varepsilon\left|z-z_{0}\right| \tag{X}\] whenever \(\left|z-z_{0}\right|<\delta\).

Since \(\int_{\partial \triangle_{n}}z^mdz=0\) for any \(m,n\ge0\), we have \[\int_{\partial \triangle_{n}} f(z) d z=\int_{\partial \triangle_{n}}\left(f(z)-f\left(z_{0}\right)-f^{\prime}\left(z_{0}\right)\left(z-z_{0}\right)\right) d z \tag{Y}\] for any \(n\ge0\).

Let \(n_{0}\in\mathbb N\) be the smallest positive integer such that \(2^{-n_{0}} L<\delta\).

Then for \(z \in \triangle_{n_{0}}\), we have \(\left|z-z_{0}\right|<2^{-n_{0}} L<\delta\).

Now we use (X) to estimate the absolute value of the integral on the right-hand side of (Y) with \(n=n_{0}\) and obtain \[\left|\int_{\partial \triangle_{n_{0}}} f(z) d z\right| \leq \varepsilon 4^{-n_{0}} L^{2} \tag{Z}.\]

Using the lower bound for (Z) with \(n=n_{0}\), we obtaun \(|J| \leq \varepsilon L^{2}\).

This is true for every \(\varepsilon>0\) and hence \(J=0\).

Thus we may suppose that \(p \in \triangle\). Let \(\triangle=\triangle(A,B,C)\) be a triangle formed by ordered triple \(A, B, C\).

First we prove that \(J=0\) when \(p\) is a vertex of \(\triangle\), say \(p=A\).

We may assume that \(A, B\) and \(C\) are not colinear otherwise the assertion follows immediately.

Let \(\varepsilon>0\) and take \(x \in[A, B], y \in[A, C]\) so that \(|x-A|<\varepsilon\) and \(|y-A|<\varepsilon\). We observe that \[J=\int_{\partial\triangle(A, x, y)} f(z) d z+\int_{\partial\triangle(x, B, y)} f(z) d z+\int_{\partial\triangle(B, C, y)} f(z) d z.\]

Further, the last two integrals are equal to zero since \(a\) does not lie in triangles \(\triangle(x, B, y)\) and \(\triangle(B, C, y)\).

Since \(f\) is continuous on compact set \(\triangle(A, x, y)\), we observe that \(K=\sup_{z\in\triangle(A, x, y)}|f(z)|<\infty\). Therefore, \[\bigg|\int_{\partial\triangle(A, x, y)} f(z) d z\bigg|\le 4 \varepsilon K \ _{\overrightarrow{\varepsilon \to 0}} \ 0.\]

Now it remains to show that \(J=0\) when \(p\) is not a vertex of \(\triangle\). Then \[J=\int_{\partial\triangle(A, B, p)} f(z) d z+\int_{\partial\triangle(B, C, p)} f(z) d z+\int_{\partial\triangle(C, A, p)} f(z) d z\] and, as proved above, all the integrals are zero. Hence \(J=0\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Cauchy’s theorem for convex sets

Let \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) be a convex open set and \(p \in \Omega\). Let \(f\) be continuous in \(\Omega\) and holomorphic in \(\Omega \backslash\{p\}\). Then \(f\) has a primitive in \(\Omega\) and \[\int_{\gamma} f(z) d z=0\] for any closed path \(\gamma\) in \(\Omega\). In particular, \(f\in H(\Omega)\).

Let \(\gamma\) be a closed path in an open convex set \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) and \(f \in H(\Omega)\). Then \[\int_{\gamma} f(z) d z=0,\] and \(f\) has a primitive function in \(\Omega\).

Let \([p, z]\) denotes the line joining from \(p\) to \(z\), and consider \[F(z)=\int_{[p, z]} f(\zeta) d \zeta \quad \text{ for }\quad z \in \Omega.\]

Observe that \([p, z]\subseteq\Omega\) since \(\Omega\) is convex. Let \(z_{0} \in \Omega\), then \[\begin{aligned} F(z)-F\left(z_{0}\right)&=\int_{[p, z]} f(\zeta) d \zeta-\int_{\left[p, z_{0}\right]} f(\zeta) d \zeta\\ &=\int_{\left[z_{0}, z\right]} f(\zeta) d \zeta \end{aligned}\] by the Cauchy–Goursat theorem, since \[\begin{aligned} 0=\int_{\partial\triangle(p, z, z_0)}f(\zeta) d \zeta&= \int_{[p, z]} f(\zeta) d \zeta +\int_{[z, z_0]} f(\zeta) d \zeta+\int_{[z_0,p]} f(\zeta) d \zeta\\ &= \int_{[p, z]} f(\zeta) d \zeta -\int_{[p, z_0]} f(\zeta) d \zeta-\int_{[z_0, z]} f(\zeta) d \zeta. \end{aligned}\]

Hence, we obtain \[\frac{F(z)-F\left(z_{0}\right)}{z-z_{0}}-f\left(z_{0}\right)=\frac{1}{z-z_{0}} \int_{\left[z_{0}, z\right]}\left(f(\zeta)-f\left(z_{0}\right)\right) d \zeta.\]

Let \(\varepsilon>0\). Since \(f\) is continuous at \(z_{0}\), there exists \(\delta>0\) such that \(\left|f(\zeta)-f\left(z_{0}\right)\right|< \varepsilon\) whenever \(\left|z-z_{0}\right|<\delta\). Thus \[\bigg|\frac{F(z)-F\left(z_{0}\right)}{z-z_{0}}-f\left(z_{0}\right)\bigg|<\varepsilon\] whenever \(\left|z-z_{0}\right|<\delta\).

This implies that \(F\) is analytic at \(z_{0}\) and \(F^{\prime}\left(z_{0}\right)= f\left(z_{0}\right)\). Since \(z_{0}\) is an arbitrary point of \(\Omega\), we have \(F \in H(\Omega)\) and \(f=F^{\prime}\) in \(\Omega\).

Moreover, \(\int_{\gamma} f(z) d z=0\), since \(f\) has a primitive \(F\) in \(\Omega\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remarks.

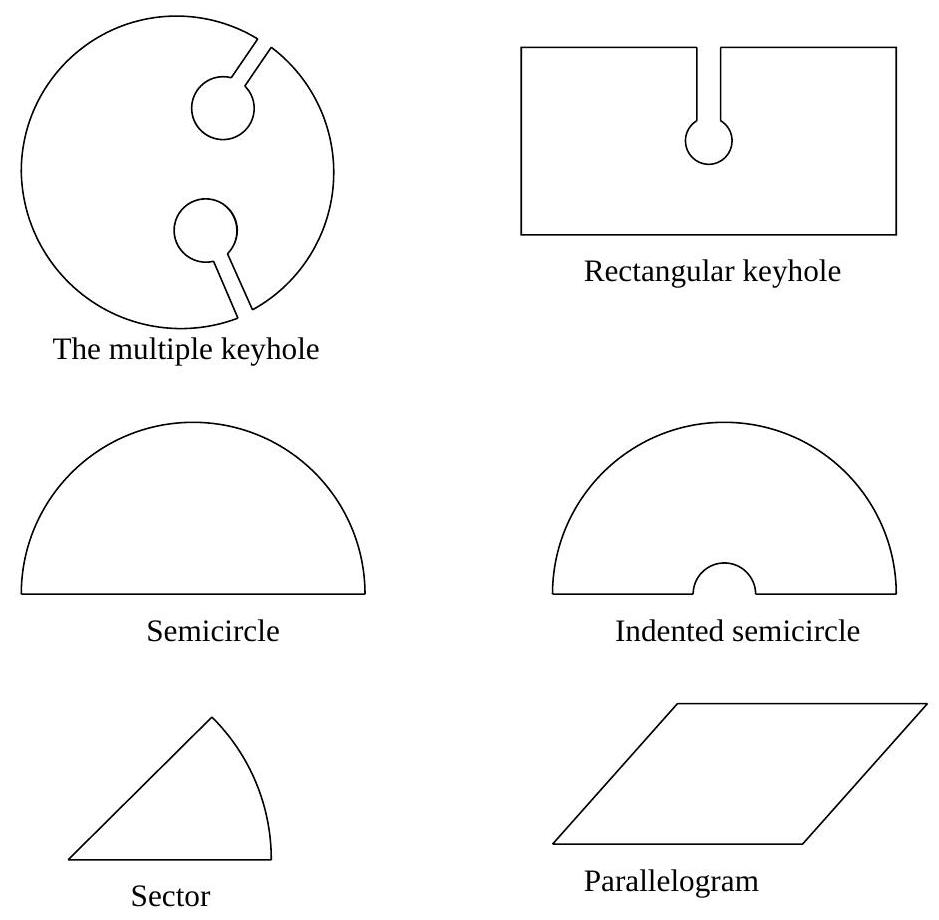

The Cauchy theorem can be proved in all the regions illustrated below, even though some of them are not convex. Explain why?

Example

We show that if \(\xi \in \mathbb{R}\), then

\[e^{-\pi \xi^{2}}=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-\pi x^{2}} e^{-2 \pi i x \xi} d x.\]

If \(\xi=0\), we know that \(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-\pi x^{2}} d x=1\).

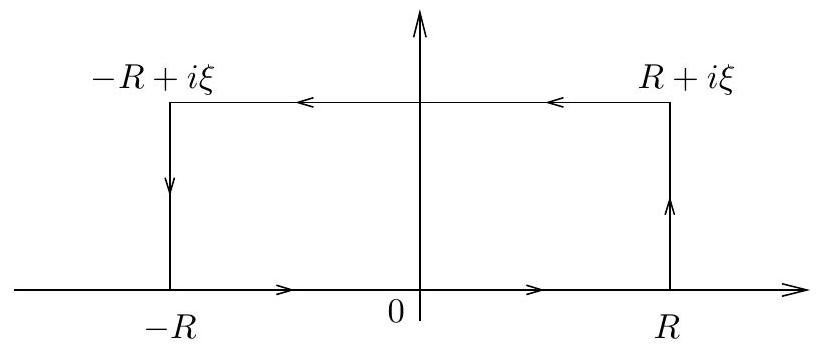

Now suppose that \(\xi>0\), and consider the function \(f(z)=e^{-\pi z^{2}}\), which is entire, and in particular holomorphic in the interior of the contour \(\gamma_{R}\) given here

The contour \(\gamma_{R}\) is a rectangle with vertices \(R, R+i \xi,-R+ i \xi,-R\) and the positive counterclockwise orientation. By Cauchy’s theorem, \[\int_{\gamma_{R}} f(z) d z=0.\]

The integral over the real segment is simply \[\int_{-R}^{R} e^{-\pi x^{2}} d x\] which converges to 1 as \(R \rightarrow \infty\).

The integral on the vertical side on the right is \[I(R)=\int_{0}^{\xi} f(R+i y) i d y=\int_{0}^{\xi} e^{-\pi\left(R^{2}+2 i R y-y^{2}\right)} i d y.\]

This integral goes to 0 as \(R \rightarrow \infty\) since \(\xi\) is fixed and we may estimate it by \[|I(R)| \leq C e^{-\pi R^{2}}.\]

Similarly, the integral over the vertical segment on the left also goes to 0 as \(R \rightarrow \infty\) for the same reasons.

Finally, the integral over the horizontal segment on top is \[\int_{R}^{-R} e^{-\pi(x+i \xi)^{2}} d x=-e^{\pi \xi^{2}} \int_{-R}^{R} e^{-\pi x^{2}} e^{-2 \pi i x \xi} d x.\]

Therefore, we find in the limit as \(R \rightarrow \infty\) that \[0=1-e^{\pi \xi^{2}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-\pi x^{2}} e^{-2 \pi i x \xi} d x\] as desired.

In the case \(\xi<0\), we then consider the symmetric rectangle, in the lower half-plane.

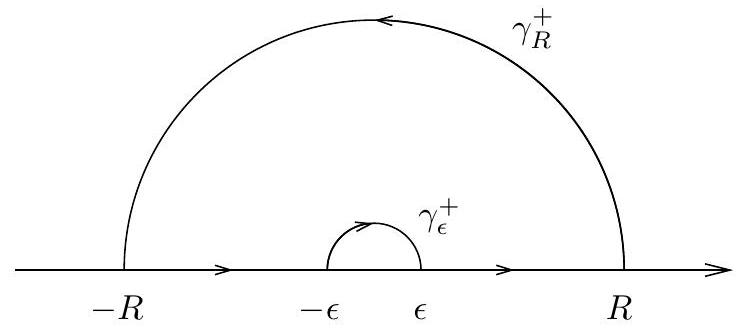

Another classical example is \[\int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{1-\cos x}{x^{2}} d x=\frac{\pi}{2}.\]

Here we consider the function \(f(z)=\left(1-e^{i z}\right) / z^{2}\), and we integrate over the indented semicircle in the upper half-plane positioned on the \(x\)-axis, as here

If we denote by \(\gamma_{\epsilon}^{+}\)and \(\gamma_{R}^{+}\)the semicircles of radii \(\epsilon\) and \(R\) with negative and positive orientations respectively, Cauchy’s theorem gives \[\int_{-R}^{-\epsilon} \frac{1-e^{i x}}{x^{2}} d x+\int_{\gamma_{\epsilon}^{+}} \frac{1-e^{i z}}{z^{2}} d z+\int_{\epsilon}^{R} \frac{1-e^{i x}}{x^{2}} d x+\int_{\gamma_{R}^{+}} \frac{1-e^{i z}}{z^{2}} d z=0\]

First we let \(R \rightarrow \infty\) and observe that \[\left|\frac{1-e^{i z}}{z^{2}}\right| \leq \frac{2}{|z|^{2}},\] so the integral over \(\gamma_{R}^{+}\) goes to zero.

Therefore \[\int_{|x| \geq \epsilon} \frac{1-e^{i x}}{x^{2}} d x=-\int_{\gamma_{\epsilon}^{+}} \frac{1-e^{i z}}{z^{2}} d z.\]

Next, note that \[f(z)=\frac{-i z}{z^{2}}+E(z)\] where \(E(z)\) is bounded as \(z \rightarrow 0\).

On \(\gamma_{\epsilon}^{+}\)we have \(z=\epsilon e^{i \theta}\) and \(d z=i \epsilon e^{i \theta} d \theta\). Thus \[\int_{\gamma_{\epsilon}^{+}} \frac{1-e^{i z}}{z^{2}} d z \rightarrow \int_{\pi}^{0}(-i i) d \theta=-\pi \quad \text { as }\quad \epsilon \rightarrow 0.\]

Taking real parts then yields \[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1-\cos x}{x^{2}} d x=\pi.\]

Since the integrand is even, the desired formula is proved.