9. Analytic branch of the complex logarithm PDF TEX

Complex logarithms

Complex logarithms and arguments

The exponential function \(S_{\alpha}\ni z\mapsto e^z\in \mathbb C\setminus\{0\}\) when restricted to the strip \(S_{\alpha}=\{x+i y: \alpha \leq y<\alpha+2 \pi\}\) is a one-to-one analytic map of this strip onto \(\mathbb C\setminus\{0\}\) the nonzero complex numbers.

We take \(\log _{\alpha}\) to be the inverse of the exponential function restricted to the strip \(S_{\alpha}= \{x+i y: \alpha \leq y<\alpha+2 \pi\}\).

We define \(\arg _{\alpha}\) to the imaginary part of \(\log _{\alpha}\).

Consequently, \(\log _{\alpha}(\exp z)=z\) for each \(z \in S_{\alpha}\), and \(\exp \left(\log _{\alpha} z\right)=z\) for all \(z \in \mathbb{C} \backslash\{0\}\).

The principal branches of the logarithm and argument functions, to be denoted by \(\operatorname{Log}\) and \(\operatorname{Arg}\), are obtained by taking \(\alpha=-\pi\).

Thus, \(\operatorname{Log} =\log _{-\pi}\) and \(\operatorname{Arg}=\arg _{-\pi}\).

If \(z \neq 0\), then \(\log _{\alpha}(z)=\log |z|+i \arg _{\alpha}(z)\), and \(\arg _{\alpha}(z)\) is the unique number in \([\alpha, \alpha+2 \pi)\) such that \[z /|z|=e^{i \arg _{\alpha}(z)}.\] In other words, the unique argument of \(z\) in \([\alpha, \alpha+2 \pi)\).

Let \(R_{\alpha}=\left\{r e^{i \alpha}: r \geq 0\right\}\). The functions \(\log _{\alpha}\) and \(\arg _{\alpha}\) are continuous at each point of the "slit" complex plane \(\mathbb{C} \backslash R_{\alpha}\), and discontinuous at each point of \(R_{\alpha}\).

The function \(\log _{\alpha}\) is analytic on \(\mathbb{C} \backslash R_{\alpha}\), and its derivative is given by \(\log _{\alpha}^{\prime}(z)=1 / z\).

Proof:

If \(w=\log _{\alpha}(z)\) with \(z \neq 0\), then \(e^{w}=z\), hence \[|z|=e^{\operatorname{Re} w}, \quad \text{ and } \quad z /|z|=e^{i \operatorname{Im} w}.\] Thus \(\operatorname{Re} w=\log |z|\), and \(\operatorname{Im} w\) is an argument of \(z /|z|\). Since \(\operatorname{Im} w\) is restricted to \([\alpha, \alpha+2 \pi)\) by definition of \(\log _{\alpha}\), it follows that \(\operatorname{Im} w\) is the unique argument for \(z\) that lies in the interval \([\alpha, \alpha+2 \pi)\).

By (a), it suffices to consider \(\arg _{\alpha}\). If \(z_{0} \in \mathbb{C} \backslash R_{\alpha}\) and \((z_{n})_{n\in\mathbb N}\) is a sequence converging to \(z_{0}\), then \(\arg _{\alpha}\left(z_{n}\right)\) must converge to \(\arg _{\alpha}\left(z_{0}\right)\). On the other hand, if \(z_{0} \in R_{\alpha} \backslash\{0\}\), there is a sequence \((z_{n})_{n\in\mathbb N}\) converging to \(z_{0}\) so that \[\lim_{n\to\infty}\arg _{\alpha}\left(z_{n}\right)= \alpha+2 \pi \neq \arg _{\alpha}\left(z_{0}\right)=\alpha.\]

Continuous logarithms and arguments

Recall from Lecture 2 the following theorem:

Let \(g\) be analytic on the open set \(\Omega_{1}\), and let \(f\) be a continuous complex-valued function on the open set \(\Omega\). Assume that

\(f(\Omega) \subseteq \Omega_{1}\),

\(g^{\prime}\) is never 0 ,

\(g(f(z))=z\) for all \(z \in \Omega\) (thus \(f\) is one-to-one).

Then \(f\) is analytic on \(\Omega\) and \(f^{\prime}=1 /\left(g^{\prime} \circ f\right)\).

By this theorem with \(g=\exp\) , \(\Omega_{1}=\mathbb{C}\), \(f=\log _{\alpha}\), and \(\Omega=\mathbb{C} \backslash R_{\alpha}\) and the fact that \(\exp\) is its own derivative we obtain that \[(\log _{\alpha} z)'=\frac{1}{z}.\] This completes the proof of the theorem.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Analytic branch of the complex logarithm

Analytic logarithm

Let \(f\) be analytic on \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\). We say that \(g\) is an analytic logarithm of \(f\) if \(g\) is analytic on \(\Omega\) and \(e^{g(z)}=f(z)\) for \(z\in\Omega\).

Remarks. Some conditions on \(\Omega\) must be imposed:

We know that \(x\mapsto e^z\) is not injective in \(\mathbb C\). To overcome this non-injectivity, we need to work with a branch of the logarithm.

If \(f(z)=0\) for some \(z\in\Omega\), then \(0=e^{g(z)}\neq0\). Thus \(f\) must be nonvanishing on \(\Omega\).

Let \(A=\{z\in\mathbb C: 1/2<|z|<2\}\), so \(A\) is an open subset of \(\mathbb C\), but there is no \(g\in H(A)\) such that \(\exp(g(z))=z\) for \(z\in A\). Otherwise, by differentiating \(\exp(g(z))=z\) we have \(g'(z)\exp(g(z))=1\), which implies \(g'(z)=1/z\), thus \(g(z)\) is a primitive of \(1/z\) in \(A\). But \(1/z\) does not have a primitive in \(A\). Thus \(\Omega\) cannot be a region with holes.

Suppose that \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) is simply connected with \(1 \in \Omega\), and \(0 \notin \Omega\). Then in \(\Omega\) there is a branch of the logarithm \(F(z)=\log _{\Omega}(z)\) so that

\(F\) is holomorphic in \(\Omega\),

\(e^{F(z)}=z\) for all \(z \in \Omega\),

\(F(r)=\log r\) whenever \(r\) is a real number and near \(1\).

In other words, each branch \(\log _{\Omega}(z)\) is an extension of the standard logarithm defined for positive numbers.

Proof: We shall construct \(F\) as a primitive of the function \(1 / z\). Since \(0 \notin \Omega\), the function \(f(z)=1 / z\) is holomorphic in \(\Omega\).

We define \[\log _{\Omega}(z)=F(z)=\int_{\gamma} f(w) d w,\] where \(\gamma\) is any path in \(\Omega\) connecting \(1\) to \(z\).

Since \(\Omega\) is simply connected, this definition does not depend on the path chosen. Indeed, if \(\gamma_0\) is any other path in \(\Omega\) joining \(1\) to \(z\), then \[\int_{\gamma_0} f(w) d w=\int_{\gamma_0-\gamma} f(w) d w+\int_{\gamma} f(w) d w=F(z),\] since by the global Cauchy theorem \(\int_{\gamma_0-\gamma} f(w) d w=0\).

Now we show that \(F\) is holomorphic and \(F^{\prime}(z)=1 / z\) for all \(z \in \Omega\).

Fix \(z_0\in \Omega\) and take \(r>0\) such that \(D(z_0, r)\subseteq \Omega\), then by the global Cauchy theorem we have \[\begin{aligned} F(z)-F(z_0)=\int_{[z, z_0]} f(w) d w. \end{aligned}\]

This implies that \[F'(z_0)=\lim_{z\to z_0}\frac{F(z)-F(z_0)}{z-z_0}=f(z_0)\] as desired. This proves (i).

To prove (ii), it suffices to show that \(z e^{-F(z)}=1\). Using that \(F^{\prime}(z)=1/z\), we differentiate the left-hand side, obtaining \[\frac{d}{d z}\left(z e^{-F(z)}\right)=e^{-F(z)}-z F^{\prime}(z) e^{-F(z)}=\left(1-z F^{\prime}(z)\right) e^{-F(z)}=0.\]

Since \(\Omega\) is connected we conclude that \(z e^{-F(z)}\) is constant.

Evaluating this expression at \(z=1\), and noting that \(F(1)=0\), we find that this constant must be \(1\).

Finally, if \(r\) is real and close to \(1\) we can choose as a path from \(1\) to \(r\) a line segment on the real axis so that \[F(r)=\int_{1}^{r} \frac{d x}{x}=\log r\] by the usual formula for the standard logarithm. This completes the proof of the theorem. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

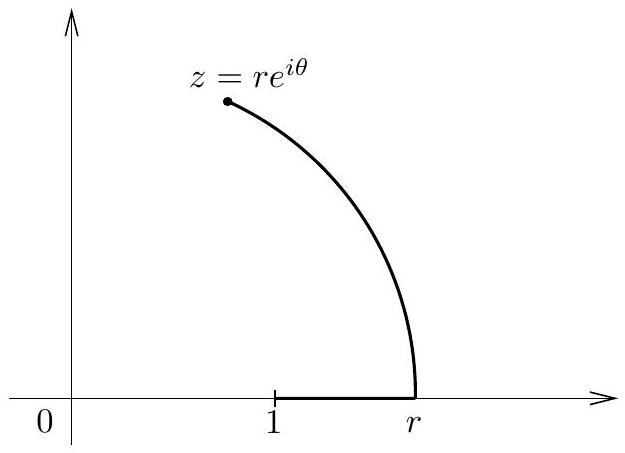

For example, in the slit plane \(\Omega=\mathbb{C}\setminus (-\infty, 0]\) we have the principal branch of the logarithm \[\log z=\log r+i \theta\] where \(z=r e^{i \theta}\) with \(|\theta|<\pi\). (Here we drop the subscript \(\Omega\), and write simply \(\log z\).) To prove this, we use the path of integration \(\gamma\) like here

If \(z=r e^{i \theta}\) with \(|\theta|<\pi\), the path consists of the line segment from \(1\) to \(r\) and the arc \(\eta\) from \(r\) to \(z\). Then \[\begin{aligned} \log z & =\int_{1}^{r} \frac{d x}{x}+\int_{\eta} \frac{d w}{w} \\ & =\log r+\int_{0}^{\theta} \frac{i r e^{i t}}{r e^{i t}} d t \\ & =\log r+i \theta \end{aligned}\]

An important observation is that in general \[\log \left(z_{1} z_{2}\right) \neq \log z_{1}+\log z_{2}.\]

For example, if \(z_{1}=e^{2 \pi i / 3}=z_{2}\), then for the principal branch of the logarithm, we have \(\log z_{1}=\log z_{2}=2 \pi i/3\), and since \(z_{1} z_{2}=e^{-2 \pi i / 3}\) we have \[-\frac{2 \pi i}{3}=\log \left(z_{1} z_{2}\right) \neq \log z_{1}+\log z_{2}.\]

Finally, for the principal branch of the logarithm the following Taylor expansion holds:

\[\begin{aligned} \log (1+z)&=z-\frac{z^{2}}{2}+\frac{z^{3}}{3}-\cdots\\ &=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^{n+1}}{n} z^{n}, \end{aligned}\] whenever \(|z|<1\).

Indeed, the derivative of both sides equals \(1 /(1+z)\), so that they differ by a constant.

Since both sides are equal to \(0\) at \(z=0\) this constant must be \(0\), and we have proved the desired Taylor expansion.

Having defined a logarithm on a simply connected domain, we can now define the powers \(z^{\alpha}\) for any \(\alpha \in \mathbb{C}\).

If \(\Omega\) is simply connected with \(1 \in \Omega\) and \(0 \notin \Omega\), we choose the branch of the logarithm with \(\log 1=0\) as above, and define \[z^{\alpha}=e^{\alpha \log z}.\]

Note that \(1^{\alpha}=1\), and that if \(\alpha=1 / n\), then \[\begin{aligned} \left(z^{1 / n}\right)^{n}&=\prod_{k=1}^{n} e^{\frac{1}{n} \log z}\\ &=e^{\sum_{k=1}^{n} \frac{1}{n} \log z}\\ &=e^{\log z}=z. \end{aligned}\]

If \(f\) is a nowhere vanishing holomorphic function in a simply connected region \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\), then there exists a holomorphic function \(g\) on \(\Omega\) such that \[f(z)=e^{g(z)}.\] The function \(g(z)\) in the theorem can be denoted by \(\log f(z)\), and determines a "branch" of that logarithm.

Proof: Fix a point \(z_{0}\) in \(\Omega\), and define a function \[g(z)=\int_{\gamma} \frac{f^{\prime}(w)}{f(w)} d w+c_{0},\] where \(\gamma\) is any path in \(\Omega\) connecting \(z_{0}\) to \(z\), and \(c_{0}\) is a complex number so that \(e^{c_{0}}=f\left(z_{0}\right)\).

This definition is independent of the path \(\gamma\) since \(\Omega\) is simply connected.

Since \(f\) is a nowhere vanishing holomorphic function in \(\Omega\), thus \(f'/f\) is a holomorphic function in \(\Omega\), and by the global Cauchy theorem its primitive \(g\) exists in \(\Omega\) and \[g^{\prime}(z)=\frac{f^{\prime}(z)}{f(z)}.\]

A simple calculation gives \[\frac{d}{d z}\left(f(z) e^{-g(z)}\right)=0\] so that \(f(z) e^{-g(z)}\) is constant.

Evaluating this expression at \(z_{0}\) we find \(f\left(z_{0}\right) e^{-c_{0}}=1\), so that \(f(z)=e^{g(z)}\) for all \(z \in \Omega\), and the proof is complete. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remarks. on the global Cauchy theorem

Let \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) be a region. Then the following statements are equivalent:

For any closed path \(\gamma\) in \(\Omega\) we have \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z)=0\) for any \(z\in\mathbb C\setminus\Omega\).

For any closed path \(\gamma\) in \(\Omega\) we have \[\int_{\gamma}f(w)dw=0\quad \text{ for every } \quad f\in H(\Omega).\]

For every \(f\in H(\Omega)\) there exists \(F\in H(\Omega)\) such that \(F'=f\).

For every \(f\in H(\Omega)\) satisfying \(1/f\in H(\Omega)\) there exists \(g\in H(\Omega)\) such that \(f=e^g\).

For every \(f\in H(\Omega)\) satisfying \(1/f\in H(\Omega)\) there exists \(g\in H(\Omega)\) such that \(f=g^2\).

Proof: We will show the following implications \[(A)\implies (B)\implies (C)\implies (D)\implies (E)\implies (D)\implies (A).\] Proof (A) \(\implies\) (B): Let \(\gamma\) be a closed path in \(\Omega\) such that \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z)=0 \quad \text{ for any } \quad z\in\mathbb C\setminus\Omega.\]

Pick \(a \in \Omega\setminus\gamma^{*}\) and define \[F(z)=(z-a) f(z).\]

Using the global Cauchy theorem, we obtain \[\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma} f(z) d z=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma} \frac{F(z)}{z-a} d z=F(a) \cdot \operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(a)=0,\] since \(F(a)=0\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (B) \(\implies\) (C): Assume that for any closed path \(\gamma\) in \(\Omega\) we have \[\int_{\gamma}f(w)dw=0\quad \text{ for every } \quad f\in H(\Omega).\]

Fix \(z_0\in\Omega\) and \(f\in H(\Omega)\). Define \[F(z)=\int_{\gamma} f(w) d w,\] where \(\gamma\) is any path in \(\Omega\) connecting \(z_0\) to \(z\).

This definition does not depend on the path chosen. Indeed, if \(\gamma_0\) is any other path in \(\Omega\) joining \(z_0\) to \(z\), then \[\int_{\gamma_0} f(w) d w=\int_{\gamma_0-\gamma} f(w) d w+\int_{\gamma} f(w) d w=F(z),\] since \(\gamma_0-\gamma\) is a closed path in \(\Omega\) and by (B) we consequently have \(\int_{\gamma_0-\gamma} f(w) d w=0\).

Now we show that \(F\) is holomorphic and \(F^{\prime}=f\) in \(\Omega\).

Fix \(a\in \Omega\) and take \(r>0\) such that \(D(a, r)\subseteq \Omega\). By (B) we obtain \[\begin{aligned} F(z)-F(a)=\int_{[z, a]} f(w) d w. \end{aligned}\]

Fix \(\varepsilon>0\) and observe that there exists \(\delta\in(0, r)\) such that \[|f(w)-f(a)|<\varepsilon \quad \text{ whenever }\quad |w-a|<\delta.\]

This implies that \[\begin{aligned} \bigg|\frac{F(z)-F(a)}{z-a}-f(a)\bigg|<\varepsilon \quad \text{ whenever }\quad |z-a|<\delta, \end{aligned}\] which proves \[F'(a)=\lim_{z\to a}\frac{F(z)-F(a)}{z-a}=f(a).\] as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (C) \(\implies\) (D): Assume that for every \(f\in H(\Omega)\) there exists \(F\in H(\Omega)\) such that \(F'=f\).

Fix \(f\in H(\Omega)\) satisfying \(1/f\in H(\Omega)\). By (C) there exists \(G\in H(\Omega)\) such that \[G'=\frac{f'}{f}.\]

Since \(f\neq0\) then \(f(z_0)=e^{c_0}\) for some \(c_0\in\mathbb C\). Define \[g(z)=G(z)-G(z_0)+c_0.\]

Then \(g'=G'=f'/f\) and consequently \[(f\exp(-g))'=f'\exp(-g)-g'f\exp(-g)=0.\]

Thus \(f\exp(-g)\) is constant in the region \(\Omega\), and in fact \[f(z_0)\exp(-g(z_0))=f(z_0)\exp(-c_0)=1.\]

Hence \(f(z)=\exp(g(z))\) as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (D) \(\implies\) (E): Suppose that for every \(f\in H(\Omega)\) satisfying \(1/f\in H(\Omega)\) there exists \(g\in H(\Omega)\) such that \(f=e^g\).

Note that \[f=e^g=\big(e^{g/2}\big)^2\] and we are done since \(e^{g/2}\in H(\Omega)\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (E) \(\implies\) (D): Suppose that for every \(f\in H(\Omega)\) satisfying \(1/f\in H(\Omega)\) there exists \(g\in H(\Omega)\) such that \(f=g^2\).

Then \(f'/f\in H(\Omega)\). Note that \[\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{\gamma}\frac{f'(z)}{f(z)}dz=\operatorname{Ind}_{f\circ\gamma}(0).\]

By (E) it follows that for any \(k\in \mathbb N\) there is \(g_k\in H(\Omega)\) such that \[g_k^{2^k}=f.\]

Now observe that \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb Z\ni \operatorname{Ind}_{f\circ\gamma}(0)=\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{\gamma}\frac{2^kg_{k}^{2^k-1}(z)g_k'(z)}{g_k^{2^k}(z)}dz=2^k\operatorname{Ind}_{g_k\circ\gamma}(0)\in \mathbb Z. \end{aligned}\]

This \(2^k\) divides \(\operatorname{Ind}_{f\circ\gamma}(0)\) for every \(k\in\mathbb N\), hence \[0=\operatorname{Ind}_{f\circ\gamma}(0)=\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{\gamma}\frac{f'(z)}{f(z)}dz.\]

Now, using implication from (B) to (C), we see that \(f'/f\) has a primitive in \(H(\Omega)\), and we conclude by reasoning similarly to the implication from (C) to (D). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (D) \(\implies\) (A): Suppose that for every \(f\in H(\Omega)\) satisfying \(1/f\in H(\Omega)\) there exists \(g\in H(\Omega)\) such that \(f=e^g\).

Let \(z\in\mathbb C\setminus\Omega\) and take \(g\in H(\Omega)\) such that \[w-z=\exp(g(w)) \quad \text{ for }\quad w\in\Omega.\]

Then we have that \(1=g'(w)(w-z)\). Hence \[\frac{1}{w-z}=g'(w)\in H(\Omega).\] In other words, \(\frac{1}{w-z}\) has a primitive in \(\Omega\).

Thus \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(z)=\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{\gamma}\frac{1}{w-z}dw=0\] for any \(z\in\mathbb C\setminus\Omega\) and any closed path \(\gamma\) in \(\Omega\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$