12. The Fourier transform PDF TEX

The Fourier transform

Functions with moderate decrease

For each \(a>0\) we denote by \(\mathfrak{F}_{a}\) the class of all functions \(f\) that satisfy the following two conditions:

The function \(f\) is holomorphic in the horizontal strip \[S_{a}=\{z \in \mathbb{C}:|\operatorname{Im}(z)|<a\}.\]

There exists a constant \(A>0\) such that \[|f(x+i y)| \leq \frac{A}{1+x^{2}} \quad \text { for all } \quad x \in \mathbb{R}\quad \text { and }\quad |y|<a.\]

In other words, \(\mathfrak{F}_{a}\) consists of those holomorphic functions on \(S_{a}\) that are of moderate decay on each horizontal \(\operatorname{line} \operatorname{Im}(z)=y\), uniformly for all \(y\in(-a, a)\).

For example, \[f(z)=e^{-\pi z^{2}}\] belongs to \(\mathfrak{F}_{a}\) for all \(a>0\).

Also, the function \[f(z)=\frac{1}{\pi} \frac{c}{c^{2}+z^{2}}\] which has simple poles at \(z= \pm c i\), belongs to \(\mathfrak{F}_{a}\) for all \(0<a<c\).

Another example is provided by \[f(z)=1 / \cosh \pi z,\] which belongs to \(\mathfrak{F}_{a}\) whenever \(|a|<1 / 2\).

Remarks.

Note also that a simple application of the Cauchy integral formula shows that if \(f \in \mathfrak{F}_{a}\), then for every \(n\in\mathbb N\), the \(n^{\text {th }}\) derivative of \(f\) belongs to \(\mathfrak{F}_{b}\) for all \(b\) with \(0<b<a\). It is a simple exercise.

Finally, we denote by \(\mathfrak{F}\) the class of all functions that belong to \(\mathfrak{F}_{a}\) for some \(a>0\). In other words, we can write \(\mathfrak{F}=\bigcup_{a>0}\mathfrak{F}_a.\)

The condition of moderate decrease can be weakened somewhat by replacing the order of decrease of \[\frac{A}{1+x^{2}} \quad \text{ by }\quad \frac{A}{1+|x|^{1+\varepsilon}}\] for any \(\varepsilon>0\). One can observe that many of the results below remain unchanged with this less restrictive condition.

Fourier transform

If \(f\) belongs to the class \(\mathfrak{F}_{a}\) for some \(a>0\), then \[|\hat{f}(\xi)| \leq B e^{-2 \pi b|\xi|},\] for any \(0 \leq b<a\), where \[\hat{f}(\xi)=\int_{\mathbb R}e^{-2\pi i x\xi}f(x)dx.\]

Proof: The case \(b=0\) simply says that \(\hat{f}\) is bounded. Indeed, we have \[|\hat{f}(\xi)|\le \int_{\mathbb R}|f(x)|dx\le \int_{\mathbb R}\frac{A}{1+x^2}dx.\] Hence we can take \(B=A\pi\) and we are done.

Now suppose \(0<b<a\) and assume first that \(\xi>0\). The main step consists of shifting the contour of integration, that is the real line, down by \(b\).

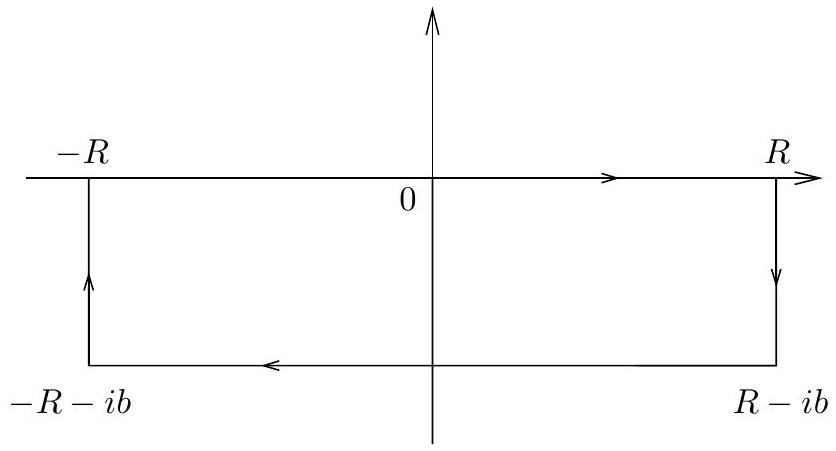

More precisely, consider the function \(g(z)=f(z) e^{-2 \pi i z \xi}\) as well as the contour

We claim that as \(R\) tends to infinity, the integrals of \(g\) over the two vertical sides converge to zero.

For example, the integral over the vertical segment on the left can be estimated by \[\begin{aligned} \left|\int_{-R-i b}^{-R} g(z) d z\right| & \leq \int_{0}^{b}\left|f(-R-i t) e^{-2 \pi i(-R-i t) \xi}\right| d t \\ & \leq \int_{0}^{b} \frac{A}{R^{2}} e^{-2 \pi t \xi} d t \\ & =O\left(1 / R^{2}\right). \end{aligned}\]

Thus \[\lim_{R\to \infty}\left|\int_{-R-i b}^{-R} g(z) d z\right|=0.\]

A similar estimate for the other side proves our claim.

Therefore, by Cauchy’s theorem applied to the large rectangle, we find in the limit as \(R\) tends to infinity that \[\hat{f}(\xi)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x-i b) e^{-2 \pi i(x-i b) \xi} d x,\] which leads to the estimate \[|\hat{f}(\xi)| \leq \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{A}{1+x^{2}} e^{-2 \pi b \xi} d x \leq B e^{-2 \pi b \xi},\] where \(B=A\pi\).

A similar argument for \(\xi<0\), but this time shifting the real line up by \(b\), allows us to finish the proof of the theorem. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Fourier inversion formula

Remark.

The previous result says that whenever \(f \in \mathfrak{F}\), then \(\hat{f}\) has rapid decay at infinity.

We remark that the further we can extend \(f\) (that is, the larger \(a\) ), then the larger we can choose \(b\), hence the better the decay.

It is possible to describe those \(f\) for which \(\hat{f}\) has the ultimate decay condition: compact support.

If \(f \in \mathfrak{F}\), then the Fourier inversion holds, namely \[f(x)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \hat{f}(\xi) e^{2 \pi i x \xi} d \xi \quad \text { for all } \quad x \in \mathbb{R}.\]

If \(A>0\) and \(B\in\mathbb R\), then \[\int_{0}^{\infty} e^{-(A+i B) \xi} d \xi= \frac{1}{A+i B}.\]

Proof: Since \(A>0\) and \(B \in \mathbb{R}\), we have \(\left|e^{-(A+i B) \xi}\right|=e^{-A \xi}\), and the integral converges. By definition \[\int_{0}^{\infty} e^{-(A+i B) \xi} d \xi=\lim _{R \rightarrow \infty} \int_{0}^{R} e^{-(A+i B) \xi} d \xi.\] However, \[\int_{0}^{R} e^{-(A+i B) \xi} d \xi=\left[-\frac{e^{-(A+i B) \xi}}{A+i B}\right]_{0}^{R},\] which tends to \(1 /(A+i B)\) as \(R\) tends to infinity. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof: We can now prove the inversion theorem.

Once again, the sign of \(\xi\) matters, so we begin by writing \[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \hat{f}(\xi) e^{2 \pi i x \xi} d \xi=\int_{-\infty}^{0} \hat{f}(\xi) e^{2 \pi i x \xi} d \xi+\int_{0}^{\infty} \hat{f}(\xi) e^{2 \pi i x \xi} d \xi.\]

For the second integral we argue as follows. Say \(f \in \mathfrak{F}_{a}\) and choose \(0<b<a\). Arguing as the proof of the previous theorem (changing the contour of integration), we get \[\hat{f}(\xi)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(u-i b) e^{-2 \pi i(u-i b) \xi} d u,\] so that with an application of the lemma and the convergence of the integration in \(\xi\), we find

\[\begin{aligned} \int_{0}^{\infty} \hat{f}(\xi) e^{2 \pi i x \xi} d \xi & =\int_{0}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(u-i b) e^{-2 \pi i(u-i b) \xi} e^{2 \pi i x \xi} d u d \xi \\ & =\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(u-i b) \int_{0}^{\infty} e^{-2 \pi i(u-i b-x) \xi} d \xi d u \\ & =\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(u-i b) \frac{1}{2 \pi b+2 \pi i(u-x)} d u \\ & =\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{f(u-i b)}{u-i b-x} d u \\ & =\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{L_{1}} \frac{f(\zeta)}{\zeta-x} d \zeta, \end{aligned}\] where \(L_{1}\) denotes the line \(\{u-i b: u \in \mathbb{R}\}\) traversed from left to right. (In other words, \(L_{1}\) is the real line shifted down by \(b\).)

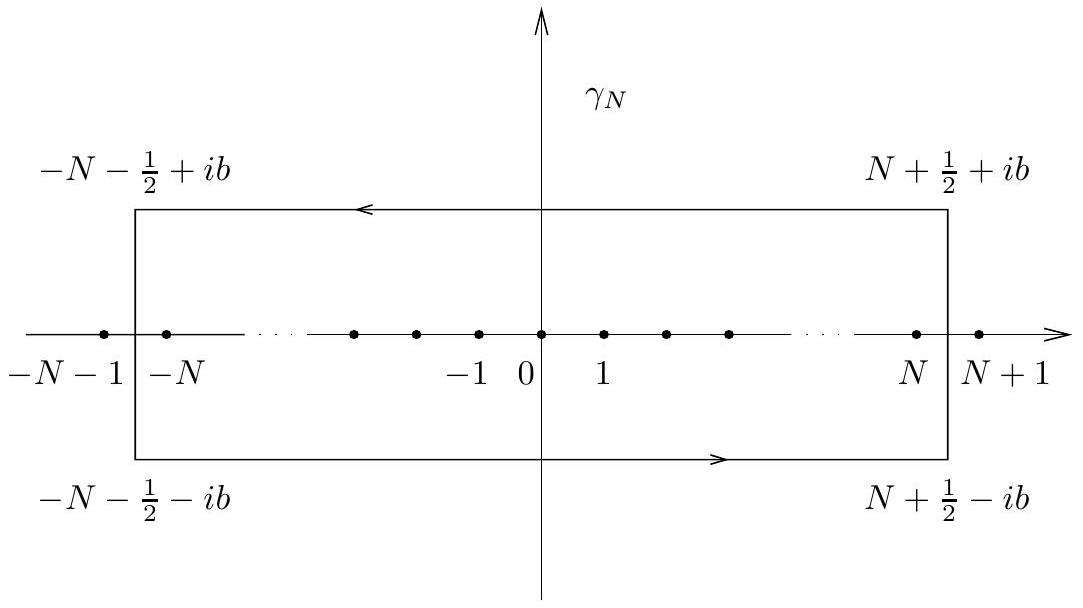

For the integral when \(\xi<0\), a similar calculation gives \[\int_{-\infty}^{0} \hat{f}(\xi) e^{2 \pi i x \xi} d \xi=-\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{L_{2}} \frac{f(\zeta)}{\zeta-x} d \zeta,\] where \(L_{2}\) is the real line shifted up by \(b\), with orientation from left to right. Now given \(x \in \mathbb{R}\), consider the contour \(\gamma_{R}\):

The function \(f(\zeta) /(\zeta-x)\) has a simple pole at \(x\) with residue \(f(x)\), so the residue formula gives \[f(x)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\gamma_{R}} \frac{f(\zeta)}{\zeta-x} d \zeta.\]

Letting \(R\) tend to infinity, one checks easily that the integral over the vertical sides goes to 0 and therefore, combining with the previous results, we get \[\begin{aligned} f(x) & =\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{L_{1}} \frac{f(\zeta)}{\zeta-x} d \zeta-\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{L_{2}} \frac{f(\zeta)}{\zeta-x} d \zeta \\ & =\int_{0}^{\infty} \hat{f}(\xi) e^{2 \pi i x \xi} d \xi+\int_{-\infty}^{0} \hat{f}(\xi) e^{2 \pi i x \xi} d \xi \\ & =\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \hat{f}(\xi) e^{2 \pi i x \xi} d \xi, \end{aligned}\] and the theorem is proved.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Poisson summation formula

If \(f \in \mathfrak{F}\), then \[\sum_{n \in \mathbb{Z}} f(n)=\sum_{n \in \mathbb{Z}} \hat{f}(n).\]

Proof: Say \(f \in \mathfrak{F}_{a}\) and choose some \(b\) satisfying \(0<b<a\).

The function \[\frac{1}{e^{2 \pi i z}-1}\] has simple poles with residue \(1 /(2 \pi i)\) at the integers.

Thus \[\frac{f(z)}{e^{2 \pi i z}-1}\] has simple poles at the integers \(n\in\mathbb Z\), with residues \(f(n) / 2 \pi i\).

We may therefore apply the residue formula to the contour \(\gamma_{N}\):

where \(N\) is an integer.

This yields \[\sum_{|n| \leq N} f(n)=\int_{\gamma_{N}} \frac{f(z)}{e^{2 \pi i z}-1} d z.\]

Letting \(N\) tend to infinity, and recalling that \(f\) has moderate decrease, we see that the sum converges to \[\sum_{n \in \mathbb{Z}} f(n).\]

Also that the integral over the vertical segments goes to \(0\).

Therefore, in the limit we get \[\sum_{n \in \mathbb{Z}} f(n)=\int_{L_{1}} \frac{f(z)}{e^{2 \pi i z}-1} d z-\int_{L_{2}} \frac{f(z)}{e^{2 \pi i z}-1} d z,\tag{*}\] where \(L_{1}\) and \(L_{2}\) are the real line shifted down and up by \(b\), respectively.

Now we use the fact that if \(|w|>1\), then \[\frac{1}{w-1}=w^{-1} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} w^{-n}\] to see that on \(L_{1}\) (where \(\left|e^{2 \pi i z}\right|>1\) ) we have \[\frac{1}{e^{2 \pi i z}-1}=e^{-2 \pi i z} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} e^{-2 \pi i n z}.\]

Also if \(|w|<1\), then \[\frac{1}{w-1}=-\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} w^{n}\] so that on \(L_{2}\) we have \[\frac{1}{e^{2 \pi i z}-1}=-\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} e^{2 \pi i n z}.\]

Substituting these observations in (*) we find that \[\begin{aligned} \sum_{n \in \mathbb{Z}} f(n) & =\int_{L_{1}} f(z)\left(e^{-2 \pi i z} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} e^{-2 \pi i n z}\right) d z+\int_{L_{2}} f(z)\left(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} e^{2 \pi i n z}\right) d z \\ & =\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \int_{L_{1}} f(z) e^{-2 \pi i(n+1) z} d z+\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \int_{L_{2}} f(z) e^{2 \pi i n z} d z \\ & =\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x) e^{-2 \pi i(n+1) x} d x+\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x) e^{2 \pi i n x} d z \\ & =\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \hat{f}(n+1)+\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \hat{f}(-n) =\sum_{n \in \mathbb{Z}} \hat{f}(n), \end{aligned}\] where we have shifted \(L_{1}\) and \(L_{2}\) back to the real line according to equation and its analogue for the shift down. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Theta function

First, we recall that the function \(e^{-\pi x^{2}}\) was its own Fourier transform: \[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-\pi x^{2}} e^{-2 \pi i x \xi} d x=e^{-\pi \xi^{2}}.\]

For fixed values of \(t>0\) and \(a \in \mathbb{R}\), the change of variables \[x \mapsto t^{1 / 2}(x+a)\] in the above integral shows that the Fourier transform of the function \(f(x)=e^{-\pi t(x+a)^{2}}\) is \[\hat{f}(\xi)=t^{-1 / 2} e^{-\pi \xi^{2} / t} e^{2 \pi i a \xi}.\]

Applying the Poisson summation formula to the pair \(f\) and \(\hat{f}\) (which belong to \(\mathfrak{F}\) ) provides the following relation: \[\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-\pi t(n+a)^{2}}=\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} t^{-1 / 2} e^{-\pi n^{2} / t} e^{2 \pi i n a}. \tag{**}\]

This identity has noteworthy consequences. For instance, the special case \(a=0\) is the transformation law for a version of the “theta function”: if we define \(\vartheta\) for \(t>0\) by the series \[\vartheta(t)=\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-\pi n^{2} t},\] then the relation (**) says precisely that \[\vartheta(t)=t^{-1 / 2} \vartheta(1 / t) \quad \text { for } \quad t>0.\]

This equation will be used to derive the key functional equation of the Riemann zeta function, and this leads to its analytic continuation.

Example

For another application of the Poisson summation formula we recall that the function \(1 / \cosh \pi x\) was also its own Fourier transform: \[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{e^{-2 \pi i x \xi}}{\cosh \pi x} d x=\frac{1}{\cosh \pi \xi}.\]

This implies that if \(t>0\) and \(a \in \mathbb{R}\), then the Fourier transform of the function \[f(x)=e^{-2 \pi i a x} / \cosh (\pi x / t),\] is \[\hat{f}(\xi)=t / \cosh (\pi(\xi+a) t),\] and the Poisson summation formula yields

\[\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{e^{-2 \pi i a n}}{\cosh (\pi n / t)} =\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{t}{\cosh (\pi(n+a) t)}.\]

Paley–Wiener type theorem

Suppose \(\hat{f}\) satisfies the decay condition \[|\hat{f}(\xi)| \leq A e^{-2 \pi a|\xi|}\] for some constants \(a, A>0\). Then \(f(x)\) is the restriction to \(\mathbb{R}\) of a function \(f(z)\) holomorphic in the strip \[S_{b}=\{z \in \mathbb{C}:|\operatorname{Im}(z)|<b\},\] for any \(0<b<a\).

Proof: Define \[f_{n}(z)=\int_{-n}^{n} \hat{f}(\xi) e^{2 \pi i \xi z} d \xi\] and note that \(f_{n}\) is entire. (Why?)

Observe also that \(f(z)\) may be defined for all \(z\) in the strip \(S_{b}\) by \[f(z)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \hat{f}(\xi) e^{2 \pi i \xi z} d \xi,\] because the integral converges absolutely by our assumption on \(\hat{f}\): it is majorized by \[A \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-2 \pi a|\xi|} e^{2 \pi b|\xi|} d \xi,\] which is finite if \(b<a\).

Moreover, for \(z \in S_{b}\), we have \[\begin{aligned} \left|f(z)-f_{n}(z)\right| & \leq A \int_{|\xi| \geq n} e^{-2 \pi a|\xi|} e^{2 \pi b|\xi|} d \xi \ _{\overrightarrow{n\to\infty}} \ 0, \end{aligned}\] and thus the sequence \((f_{n})_{n\in\mathbb N}\) converges to \(f\) uniformly in \(S_{b}\), which, proves the theorem. (Why?) $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$