15. The Runge theorem PDF TEX

The Riemann mapping theorem

The Riemann mapping theorem

\(D=\{z\in \mathbb{C}: |z|<1\}\) is the open unit disc centered at the origin.

Let \(\Omega \neq \mathbb{C}\) be a simply connected region. Then \(\Omega\) is conformally equivalent to \(D\). Moreover, the assumption \(\Omega \neq \mathbb{C}\) is necessary.

Remark.

In view of the Liouville theorem, the assumption \(\Omega \neq \mathbb{C}\) is necessary. Indeed, if \(f:\mathbb C\to D\) is a conformal map, then \(f\) is bounded, since \(|f(z)|<1\) for all \(z\in \mathbb C\). Hence, by the Liouville theorem \(f\) must be constant, but then it cannot be injective.

However, \(\mathbb C\) and \(D\) are homeomorphic. The mapping \[\mathbb C\ni z\mapsto \frac{z}{1+|z|}\in D\] is the desired homeomorphism.

The Runge theorem

Rational functions

A rational function \(f\) is, by definition, a quotient of two polynomials \(P\) and \(Q\), i.e. \[f=P / Q.\]

By the fundamental theorem of algebra every nonconstant polynomial is a product of factors of degree \(1\).

Thus, we may assume that \(P\) and \(Q\) have no such factors in common.

Then \(f\) has a pole at each zero of \(Q\) (the pole of \(f\) has the same order as the zero of \(Q\)).

If we subtract the corresponding principal parts, we obtain a rational function whose only singularity is at \(\infty\) and which is therefore a polynomial.

Every rational function \[f=P / Q,\] has thus a representation of the form \[f(z)=A_{0}(z)+\sum_{j=1}^{k} A_{j}\left(\left(z-a_{j}\right)^{-1}\right), \tag{*}\] where \(A_{0}, A_{1}, \ldots, A_{k}\) are polynomials, \(A_{1}, \ldots, A_{k}\) have no constant term, and \(a_{1}\), \(\ldots, a_{k}\) are the distinct zeros of \(Q\);

Representation (*) is called the partial fractions decomposition of the rational function \(f\).

Sets of oriented intervals

Let \(\Phi\) be a finite collection of oriented intervals in the plane.

For each point \(p\), let \(m_{I}(p)\), [resp. \(m_{E}(p)\)] be the number of members of \(\Phi\) that have initial point [resp. end point] \(p\). If \(m_{I}(p)=m_{E}(p)\) for every \(p\), we shall say that \(\Phi\) is balanced.

Construction If \(\Phi\neq\varnothing\) is balanced, the following construction can be carried out.

Pick \(\gamma_{1}=\left[a_{0}, a_{1}\right] \in \Phi\). Assume \(k \geq 1\), and assume that distinct members \(\gamma_{1}, \ldots, \gamma_{k}\) of \(\Phi\) have been chosen in such a way that \(\gamma_{i}=\left[a_{i-1}, a_{i}\right]\) for \(1 \leq i \leq k\). If \(a_{k}=a_{0}\), stop. If \(a_{k} \neq a_{0}\), and if precisely \(r\) of the intervals \(\gamma_{1}, \ldots, \gamma_{k}\) have \(a_{k}\) as end point, then only \(r-1\) of them have \(a_{k}\) as initial point; since \(\Phi\) is balanced, \(\Phi\) contains at least one other interval, say \(\gamma_{k+1}\), whose initial point is \(a_{k}\).

Since \(\Phi\) is finite, we must return to \(a_{0}\) eventually, say at the \(n\)th step.

Then join the intervals \(\gamma_{1}, \ldots, \gamma_{n}\) (in this order) to form a closed path.

The remaining members of \(\Phi\) still form a balanced collection to which the above construction can be applied.

It follows that the members of \(\Phi\) can be so numbered that they form finitely many closed paths. The sum of these paths is a cycle.

Hence, we conclude, if \(\Phi=\left\{\gamma_{1}, \ldots, \gamma_{N}\right\}\) is a balanced collection of oriented intervals, and if \(\Gamma=\gamma_{1} \dot{+} \cdots \dot{+} \gamma_{N}\), then \(\Gamma\) is a cycle.

If \(K\subset\mathbb C\) is a compact subset of an open set \(\Omega\neq \varnothing\), then there is a cycle \(\Gamma\) in \(\Omega\setminus K\) such that the Cauchy formula \[f(z)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} \frac{f(\zeta)}{\zeta-z} d \zeta \tag{**}\] holds for every \(f \in H(\Omega)\) and for every \(z \in K\).

Cauchy theorem for compact sets

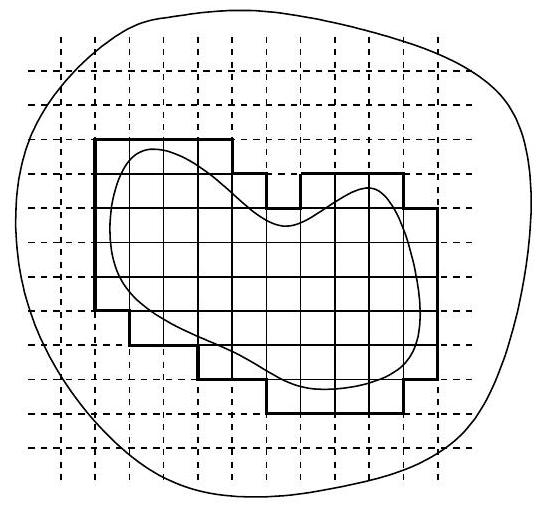

Proof: Since \(K\) is compact and \(\Omega\) is open, there exists an \(\eta>0\) such that the distance from any point of \(K\) to any point outside \(\Omega\) is at least \(2 \eta\).

Construct a grid of horizontal and vertical lines in the plane, such that the distance between any two adjacent horizontal lines is \(\eta\), and likewise for the vertical lines.

Let \(Q_{1}, \ldots, Q_{m}\) be those squares (closed 2-cells) of edge \(\eta\) which are formed by this grid and which intersect \(K\).

Then \(Q_{r} \subset \Omega\) for \(r=1, \ldots, m\).

If \(a_{r}\) is the center of \(Q_{r}\) and \(a_{r}+b\) is one of its vertices, let \(\gamma_{r k}\) be the oriented interval \[\gamma_{r k}=\left[a_{r}+i^{k} b, a_{r}+i^{k+1} b\right],\] and define \[\partial Q_{r}=\gamma_{r 1} \dot{+} \gamma_{r 2} \dot{+} \gamma_{r 3} \dot{+} \gamma_{r 4} \quad\text{ for} \quad r=1, \ldots, m.\]

It is then easy to check that \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\partial Q_{r}}(\alpha)= \begin{cases}1 & \text { if } \alpha \text { is in the interior of } Q_{r}, \\ 0 & \text { if } \alpha \text { is not in } Q_{r}.\end{cases}\]

Let \(\Sigma\) be the collection of all \(\gamma_{r k}\) with \(1 \leq r \leq m\), and \(1 \leq k \leq 4\). It is clear that \(\Sigma\) is balanced.

Remove those members of \(\Sigma\) whose opposites also belong to \(\Sigma\).

Let \(\Phi\) be the collection of the remaining members of \(\Sigma\). Then \(\Phi\) is balanced. Let \(\Gamma\) be the cycle constructed from \(\Phi\).

If an edge \(E\) of some \(Q_{r}\) intersects \(K\), then the two squares in whose boundaries \(E\) lies intersect \(K\). Hence \(\Sigma\) contains two oriented intervals which are each other’s opposites and whose range is \(E\). These intervals do not occur in \(\Phi\).

Thus \(\Gamma\) is a cycle in \(\Omega\setminus K\).

The construction of \(\Phi\) from \(\Sigma\) shows also that

\[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=\sum_{r=1}^{m} \operatorname{Ind}_{\partial Q_{r}}(\alpha),\] if \(\alpha\) is not in the boundary of any \(Q_{r}\). Hence, we obtain \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)= \begin{cases}1 & \text { if } \alpha \text { is in the interior of some } Q_{r}, \\ 0 & \text { if } \alpha \text { lies in no } Q_{r}. \end{cases}\]

If \(z \in K\), then \(z \notin \Gamma^{*}\), and \(z\) is a limit point of the interior of some \(Q_{r}\). Since the left side of \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)\) is constant in each component of the complement of \(\Gamma^{*}\), we obtain

\[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(z)= \begin{cases}1 & \text { if } z \in K,\\ 0 & \text { if } z \notin \Omega. \end{cases}\]

Now (**) follows from the global Cauchy theorem.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Runge’s theorem

Suppose \(K\subset \mathbb C\) is a compact set and \((\alpha_{j})_{j\in\mathbb N}\) is a set which contains one point in each component of \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K\). If \(\Omega\) is open, and \(\Omega \supset K\), and \(f \in H(\Omega)\), and \(\varepsilon>0\), there exists a rational function \(R\), all of whose poles lie in the prescribed set \((\alpha_{j})_{j\in\mathbb N}\), such that \[|f(z)-R(z)|<\varepsilon\] for every \(z \in K\).

Remark.

Note that \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K\) has at most countably many components.

Note also that the preassigned point in the unbounded component of \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K\) may very well be \(\infty\); in fact, this happens to be the most interesting choice.

Proof: We consider the Banach space \(C(K)\) whose members are the continuous complex functions on \(K\), with the supremum norm. Let \(M\) be the linear subspace of \(C(K)\) which consists of the restrictions to \(K\) of those rational functions which have all their poles in \((\alpha_{j})_{j\in\mathbb N}\).

The theorem asserts that \(f\) is in the closure of \(M\).

As a consequence of the Hahn–Banach theorem, this is equivalent to saying that every bounded linear functional \(\Lambda\) on \(C(K)\) which vanishes on \(M\) also vanishes at \(f\), i.e. \[\Lambda(f)=0.\]

By the the Riesz representation theorem (it is covered in 502) there exists a complex Borel measure \(\mu\) on \(K\) such \[\Lambda(f)=\int_K f(x)d\mu(x) \quad \text{ for every } \quad f\in C(K).\]

Therefore we have to prove the following assertion:

If \(\mu\) is a complex Borel measure on \(K\) such that \[\int_{K} R d \mu=0 \quad \text{ for every }\quad R\in M,\] and if \(f \in H(\Omega)\), then we also have \[\int_{K} f d \mu=0.\]

So let us assume that \(\mu\) is a complex Borel measure on \(K\) as above, and define \[h(z)=\int_{K} \frac{d \mu(\zeta)}{\zeta-z} \quad \text{ for } \quad z\in \mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K.\]

Then \(h \in H(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K)\). (Why?)

Let \(V_{j}\) be the component of \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K\) which contains \(\alpha_{j}\), and suppose \(D\left(\alpha_{j} ; r\right) \subset V_{j}\). If \(\alpha_{j} \neq \infty\) and if \(z\) is fixed in \(D\left(\alpha_{j} ; r\right)\), then \[\frac{1}{\zeta-z}=\frac{1}{\zeta-\alpha_j}\frac{1}{1-\frac{z-\alpha_j}{\zeta-\alpha_j}}=\lim _{N \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{n=0}^{N} \frac{\left(z-\alpha_{j}\right)^{n}}{\left(\zeta-\alpha_{j}\right)^{n+1}}\] uniformly for \(\zeta \in K\).

Now observe that \[h(z)=\int_{K} \frac{d \mu(\zeta)}{\zeta-z}=\lim_{N\to \infty}\sum_{n=0}^{N}\int_{K} \frac{\left(z-\alpha_{j}\right)^{n}}{\left(\zeta-\alpha_{j}\right)^{n+1}}d \mu(\zeta)=0,\] since \(\left(z-\alpha_{j}\right)^{n}\left(\zeta-\alpha_{j}\right)^{-n-1}\in M\), and \(\int_{K} R d \mu=0\) for every \(R\in M\).

Hence \(h(z)=0\) for all \(z \in D\left(\alpha_{j} ; r\right)\). This implies that \(h(z)=0\) for all \(z \in V_{j}\), by the uniqueness theorem.

If \(\alpha_{j}=\infty\), and if \(z\) is fixed in \(D\left(\infty; r\right)\), i.e. \(|z|>r\), then \[\frac{1}{\zeta-z}=-\frac{1}{z}\frac{1}{1-\frac{\zeta}{z}} =-\lim _{N \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{n=0}^{N} z^{-n-1} \zeta^{n}\] uniformly for \(\zeta \in K\).

Hence, as before, we deduce that \(h(z)=0\) in \(D(\infty ; r)\), hence in \(V_{j}\).

We have thus proved that

\[h(z)=0 \quad\text{ for } \quad z \in \mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K.\]

Now choose a cycle \(\Gamma\) in \(\Omega\setminus K\), as in the previous theorem, then \[f(z)=\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} \frac{f(\zeta)}{\zeta-z} d \zeta\] holds for every \(z \in K\).

An application of Fubini’s theorem (legitimate, since we are dealing with Borel measures and continuous functions on compact spaces), combined with \(h(z)=0\) for \(z \in \mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K\), gives \[\begin{aligned} \int_{K} f(\zeta) d \mu(\zeta) & =\int_{K} \left[\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} \frac{f(w)}{w-\zeta} d w\right]d\mu(\zeta). \\ & =\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} f(w) d w \int_{K} \frac{d \mu(\zeta)}{w-\zeta} \\ & =-\frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int_{\Gamma} f(w) h(w) d w=0, \end{aligned}\] since \(h(w)=0\) on \(\Gamma^{*} \subset \Omega\setminus K\subseteq \mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K\).

Thus \[\int_{K} f(\zeta) d \mu(\zeta)\] holds for any \(f\in H(\Omega)\), and the proof is complete.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Runge’s theorem (approximation by polynomials)

The following special case is of particular interest.

Suppose \(K\subset\mathbb C\) is a compact set, \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K\) is connected, and \(f \in H(\Omega)\), where \(\Omega\) is some open set containing \(K\). Then there is a sequence \((P_{n})_{n\in\mathbb N}\) of polynomials such that \(\lim_{n\to\infty}P_{n}(z) = f(z)\) uniformly on \(K\).

Proof: Since \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K\) has now only one component, we need only one point \(\alpha_{j}\) to apply the previous theorem, and we may take \(\alpha_{j}=\infty\).

Runge’s theorem

Remark.

The preceding result is false for every compact \(K\) in the plane such that \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K\) is not connected.

Namely, in that case \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K\) has a bounded component \(V\). Choose \(\alpha \in V\), set \(f(z)=(z-\alpha)^{-1}\), and let \(m=\max \{|z-\alpha|: z \in K\}\).

Suppose that \(P\) is a polynomial, such that \(|P(z)-f(z)|<1 / m\) for all \(z \in K\). Then \[|(z-\alpha) P(z)-1|<1 \quad \text{ for } \quad z \in K \tag{A}\]

In particular, (A) holds if \(z\) is in the boundary of \(V\); since the closure of \(V\) is compact, the maximum modulus theorem shows that (A) holds for every \(z \in V\); taking \(z=\alpha\), we obtain \(1<1\).

Hence the uniform approximation is not possible.

Recall the following lemma from the previous lecture:

Let \(\Omega\) be an open subset of \(\mathbb C\). Then there exists a sequence \((K_{n})_{n \in\mathbb N}\subseteq \Omega\) of compact sets such that \[\Omega=\bigcup_{n=1}^{\infty} K_{n}\quad \text{ and } \quad K_{n} \subseteq \operatorname{int} K_{n+1} \quad \text{ for } \quad n\in\mathbb N,\] where \(\operatorname{int}K_{n+1}\) denotes the interior of \(K_{n+1}\). Further for a compact set \(K\subseteq \Omega\), we have \(K \subseteq K_{n}\) for some \(n \in\mathbb N\).

Remark. From this lemma we can also deduce that every component of \(\mathbb{C}_{\infty}\setminus K_n\) contains a component of \(\mathbb{C}_{\infty}\setminus \Omega\) for \(n\in\mathbb N\).

This can be seen by recalling that for every \(n \in\mathbb N\), we defined \[K_n=\overline{D}(0, n)\cap\{z \in\Omega: d(z, \mathbb{C}\setminus\Omega) \geq 1/n\}.\]

Setting \(D(\infty, n)=\{z\in\mathbb C: |z|>n\}\), we see \[V_n=K_n^c=D(\infty, n)\cup\bigcup_{a\not\in\Omega}D(a, 1/n).\]

Therefore, each disc from \(V_n\) intersects \(\mathbb{C}_{\infty}\setminus \Omega\).

Each disc from \(V_n\) is connected, hence each component of \(V_n\) intersects \(\mathbb{C}_{\infty}\setminus \Omega\).

Since \(V_n\supseteq \mathbb{C}_{\infty}\setminus \Omega\), no component of \(\mathbb{C}_{\infty}\setminus \Omega\) can intersect two components of \(V_n\).

Hence, every component of \(\mathbb{C}_{\infty}\setminus K_n\) contains a component of \(\mathbb{C}_{\infty}\setminus \Omega\) for \(n\in\mathbb N\).

Let \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\) be an open set, let \(A\) be a set which has one point in each component of \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus\Omega\), and assume that \(f \in H(\Omega)\). Then:

There is a sequence \((R_{n})_{n\in\mathbb N}\) of rational functions, with poles only in \(A\), such that \(\lim_{n\to\infty}R_{n}= f\) uniformly on compact subsets of \(\Omega\).

In the special case in which \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus\Omega\) is connected, we may take \(A=\{\infty\}\) and thus obtain polynomials \(P_{n}\) such that \(\lim_{n\to\infty}P_{n}= f\) uniformly on compact subsets of \(\Omega\).

Remark.

Observe that \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus\Omega\) may have uncountably many components; for instance, we may have \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus\Omega=\{\infty\} \cup C\), where \(C\) is a Cantor set.

Proof: Choose a sequence of compact sets \((K_{n})_{n\in\mathbb N}\) in \(\Omega\), as in the previous lemma. Fix \(n\in\mathbb N\), for the moment.

Since each component of \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K_{n}\) contains a component of \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus\Omega\), each component of \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K_{n}\) contains a point of \(A\), so the previous theorem gives us a rational function \(R_{n}\) with poles in \(A\) such that \[\left|R_{n}(z)-f(z)\right|<\frac{1}{n} \quad\text{ for all } \quad z \in K_{n}.\]

If now \(K\subset \Omega\) is compact, there exists an \(N\in \mathbb N\) such that \(K \subset K_{n}\) for all \(n \geq N\). It follows from the previous inequality that

\[\left|R_{n}(z)-f(z)\right|<\frac{1}{n} \quad \text{ for all } \quad z \in K,\text{ and } n \geq N,\] which completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Mittag–Leffler theorem

Runge’s theorem will now be used to prove that meromorphic functions can be constructed with arbitrarily preassigned poles.

Suppose \(\Omega\subseteq\mathbb C\) is an open set, \(A \subset \Omega\), and \(A\) has no limit point in \(\Omega\), and to each \(\alpha \in A\) there are associated a positive integer \(m(\alpha)\) and a rational function \[P_{\alpha}(z)=\sum_{j=1}^{m(\alpha)} c_{j, \alpha}(z-\alpha)^{-j}.\] Then there exists a meromorphic function \(f\) in \(\Omega\), whose principal part at each \(\alpha \in A\) is \(P_{\alpha}\) and which has no other poles in \(\Omega\).

Proof: We choose a sequence \((K_{n})_{n\in \mathbb N}\) of compact sets in \(\Omega\), as in the previous lemma. Then \(K_{n}\subseteq \operatorname{int} K_{n+1}\) for all \(n\in\mathbb N\), and every compact subset of \(\Omega\) lies in some \(K_{n}\), for some \(n\in\mathbb N\). Moreover, every component of \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus K_{n}\) contains a component of \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus\Omega\).

Set \(A_{1}=A \cap K_{1}\), and \(A_{n}=A \cap\left(K_{n}\setminus K_{n-1}\right)\) for \(n\ge 2\).

Since \(A_{n} \subset K_{n}\) and \(A\) has no limit point in \(\Omega\) (hence none in \(K_{n}\)), each \(A_{n}\) is a finite set.

Set \[Q_{n}(z)=\sum_{\alpha \in A_{n}} P_{\alpha}(z) \quad\text{ for } \quad n\in\mathbb N.\]

Since each \(A_{n}\) is finite, each \(Q_{n}\) is a rational function. The poles of \(Q_{n}\) lie in \(K_{n}\setminus K_{n-1}\), for \(n \geq 2\). In particular, \(Q_{n}\) is holomorphic in an open set containing \(K_{n-1}\).

It now follows from Runge’s theorem that there exist rational functions \(R_{n}\), all of whose poles are in \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus\Omega\), such that \[\left|R_{n}(z)-Q_{n}(z)\right|<2^{-n} \quad\text{ for all } \quad z \in K_{n-1}.\]

We claim that \[f(z)=Q_{1}(z)+\sum_{n=2}^{\infty}\left(Q_{n}(z)-R_{n}(z)\right) \quad\text{ for all }\quad z \in \Omega\] has the desired properties.

Fix \(N\in \mathbb N\). On \(K_{N}\), we have \[f=Q_{1}+\sum_{n=2}^{N}\left(Q_{n}-R_{n}\right)+\sum_{N+1}^{\infty}\left(Q_{n}-R_{n}\right).\]

Since \(\left|R_{n}(z)-Q_{n}(z)\right|<2^{-n}\) on \(K_{n-1}\), then each term in the last sum is less than \(2^{-n}\) on \(K_{N}\); hence this last series converges uniformly on \(K_{N}\), to a function which is holomorphic in the interior of \(K_{N}\).

The function \(f-\left(Q_{1}+\cdots+Q_{N}\right)\) is holomorphic in the interior of \(K_{N}\), since the poles of each \(R_{n}\) are outside \(\Omega\).

Thus \(f\) has precisely the prescribed principal parts in the interior of \(K_{N}\), and hence in \(\Omega\), since \(N\) was arbitrary. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Characterization of simply connectedness

For a region \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\), each of the following conditions implies all the others.

\(\Omega\) is homeomorphic to the open unit disc \(D\).

\(\Omega\) is simply connected.

\(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(\alpha)=0\) for every closed path \(\gamma\) in \(\Omega\) and for every \(\alpha \in \mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus\Omega\).

\(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus\Omega\) is connected.

Every \(f \in H(\Omega)\) can be approximated by polynomials, uniformly on compact subsets of \(\Omega\).

For every \(f\in H(\Omega)\) and every closed path \(\gamma\) in \(\Omega\) we have \(\int_{\gamma} f(z) d z=0\).

To every \(f \in H(\Omega)\) corresponds an \(F \in H(\Omega)\) such that \(F^{\prime}=f\).

If \(f \in H(\Omega)\) and \(1 / f \in H(\Omega)\), there exists a \(g \in H(\Omega)\) such that \(f=\exp (g)\).

If \(f \in H(\Omega)\) and \(1 / f \in H(\Omega)\), there exists a \(\varphi \in H(\Omega)\) such that \(f=\varphi^{2}\).

Proof (a) \(\implies\) (b). To say that \(\Omega\) is homeomorphic to \(D\) means that there is a continuous one-to-one mapping \(\psi: \Omega\to D\) whose inverse \(\psi^{-1}\) is also continuous.

If \(\gamma\) is a closed curve in \(\Omega\), with parameter interval \([0,1]\), define \[H(s, t)=\psi^{-1}(t \psi(\gamma(s)))\]

Then \(H: I^{2} \rightarrow \Omega\) is continuous; \(H(s, 0)=\psi^{-1}(0)\) is constant; and \(H(s, 1)=\gamma(s)\); and \(H(0, t)=H(1, t)\) because \(\gamma(0)=\gamma(1)\).

Thus \(\gamma\) is null-homotopic in \(\Omega\), hence \(\Omega\) is simply connected.

Proof (b) \(\implies\) (c). If (b) holds then every closed curve \(\Gamma\) in \(\Omega\) is null-homotopic, that is, there exists a continuous \(H: I^{2} \rightarrow \Omega\) such that \[\begin{gathered} H(s, 0)=\Gamma(s), \quad H(s, 1)=\gamma(s),\quad \text{ for all }\quad s\in I,\\ \quad H(0, t)=H(1, t) \quad \text{ for all }\quad t\in I, \end{gathered}\] where \(\gamma\) is a constant curve. Hence \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(\alpha)=0\) whenever \(\alpha\not\in \Omega\).

Recall the following result:

Theorem.If \(\Gamma_{0}\) and \(\Gamma_{1}\) are \(\Omega\)-homotopic closed paths in a region \(\Omega\subseteq \mathbb C\), and if \(\alpha \notin \Omega\), then \[\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{1}}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma_{0}}(\alpha).\]

Invoking this result, we obtain that \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(\alpha)=\operatorname{Ind}_{\gamma}(\alpha)=0\) for \(\alpha\not\in \Omega\) as desired completing the proof of implication from (b) to (c). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (c) \(\implies\) (d). Assume (d) is false. Then \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus\Omega\) is a closed subset of \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\) which is not connected. It follows that \(\mathbb C_{\infty}\setminus\Omega\) is the union of two nonempty disjoint closed sets \(H\) and \(K\).

Let \(H\) be the one that contains \(\infty\). Let \(W\) be the complement of \(H\), relative to the plane. Then \(W=\Omega \cup K\). Since \(K\) is compact, Cauchy theorem for compact sets (with \(f=1\)) shows that there is a cycle \(\Gamma\) in \(W\setminus K=\Omega\) such that \(\operatorname{Ind}_{\Gamma}(z)=1\) for \(z \in K\).

Since \(K \neq \varnothing\), (c) fails, and we are done. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (d) \(\implies\) (e). This is part follows from Runge’s theorem. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (e) \(\implies\) (f). Choose \(f \in H(\Omega)\), let \(\gamma\) be a closed path in \(\Omega\), and choose polynomials \(P_{n}\) which converge to \(f\), uniformly on \(\gamma^{*}\). Since \(\int_{\gamma} P_{n}(z) d z=0\) for all \(n\in\mathbb N\), we conclude that \((f)\) holds.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (f) \(\implies\) (g). Assume \((f)\) holds, fix \(z_{0} \in \Omega\), and put \[F(z)=\int_{\Gamma(z)} f(\zeta) d \zeta \quad\text{ for all }\quad z \in \Omega,\] where \(\Gamma(z)\) is any path in \(\Omega\) from \(z_{0}\) to \(z\).

This defines a function \(F\) in \(\Omega\). For if \(\Gamma_{1}(z)\) is another path from \(z_{0}\) to \(z\) in \(\Omega\), then \(\Gamma\) followed by the opposite of \(\Gamma_{1}\) is a closed path in \(\Omega\), the integral of \(f\) over this closed path is \(0\), so \(F\) is well-defined, i.e. \(F\) is not affected if \(\Gamma(z)\) is replaced by \(\Gamma_{1}(z)\).

We now verify that \(F^{\prime}=f\). Fix \(a \in \Omega\), then there exists an \(r>0\) such that \(D(a ; r) \subseteq \Omega\). For \(z \in D(a ; r)\) we can compute \(F(z)\) by integrating \(f\) over a path \(\Gamma(a)\), followed by the interval \([a, z]\).

Hence, for \(z \in D^{\prime}(a ; r)\), we have \[\frac{F(z)-F(a)}{z-a}=\frac{1}{z-a} \int_{[a, z]} f(\zeta) d \zeta,\] and the continuity of \(f\) at \(a\) implies now that \(F^{\prime}(a)=f(a)\).

Proof (g) \(\implies\) (h). If \(f \in H(\Omega)\) and \(f\) has no zero in \(\Omega\), then \(f^{\prime} / f \in H(\Omega)\), and (g) implies that there exists a \(g \in H(\Omega)\) so that \(g^{\prime}=f^{\prime} / f\). We can add a constant to \(g\), so that \(\exp(g\left(z_{0}\right))=f\left(z_{0}\right)\) for some \(z_{0} \in \Omega\). Our choice of \(g\) shows that \((f e^{-g})'=0\) in \(\Omega\), hence \(f e^{-g}\) is constant (since \(\Omega\) is connected), and \(f=e^{g}\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (h) \(\implies\) (i). By (h) we have \(f=e^{g}\). Set \(\varphi=\exp \left(\frac{1}{2} g\right)\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (i) \(\implies\) (a). If \(\Omega\) is the whole plane, then \(\Omega\) is homeomorphic to \(D\), take \(z\mapsto z /(1+|z|)\). If \(\Omega\) is a proper subregion of the plane which satisfies \((i)\), then there actually exists a holomorphic homeomorphism of \(\Omega\) onto \(D\) by the Riemann mapping theorem. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$