7. Cantor set and Cantor function, Nonmeasurable sets PDF TEX

Some properties of Lebesgue measure

Some properties of Lebesgue measure

Let \(\lambda\) be the Lebesgue measure on \(\mathbb{R}\). Then we have-

\(\lambda(\{x\})=0\) for any \(x \in \mathbb{R}\),

-

\(\mathbb{Q}\) has Lebesgue measure \(0\). In fact, \(\lambda(U)=0\) for any countable set \(U \subseteq \mathbb{R}\),

-

If \(U\) is open in \(\mathbb{R}\), then \(\lambda(U)>0\),

-

If \(E\) is a null set in \(\mathbb{R}\) (i.e. \(\lambda(E)=0\)) then \(E^c\) is dense in \(\mathbb{R}\).

Proof. For any open interval \(I \subseteq \mathbb{R}\) we have \(\lambda(I)>0\). Since \(\lambda(E)=0\) this means that \(E\) cannot contain any open interval. Thus \(E^c \cap I \neq \varnothing\) for any interval \(I \subseteq \mathbb{R}\) but this means that \(E^c\) is dense in \(\mathbb{R}.\)$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Nowhere dense set with positive Lebesgue measure

-

Let \(\mathbb{Q} \cap [0,1]=\{r_j: j \in \mathbb{N}\}\) and given \(\varepsilon>0\) let \(I_j\) be the open interval of length \(\varepsilon2^{-j}\), which is centered at \(r_j\). Then the set \[U=(0,1) \cap \bigcup_{j=1}^{\infty}I_j\] is open and dense in \(\mathbb{R}\), since \(U \supseteq \mathbb{Q} \cap (0,1)\). Thus \(U\) is topologically large but small in the sense of measure, since \[\lambda(U) \leq \sum_{j=1}^{\infty}\lambda(I_j) \leq \sum_{j=1}^{\infty}\frac{\varepsilon}{2^j}=\varepsilon.\]

-

If \(K=[0,1] \setminus U\) then \(K\) is closed and nowhere dense thus topologically small but large in the sense of measure since \[\lambda(K)=1-\lambda(U) \geq 1-\varepsilon.\]

Cantor set

Accumulation point, isolated point, perfect set

Definition. Let \((X,\rho)\) be a metric space, \(x \in X\) is called an accumulation point of \(E \subseteq X\) if for every open set \(U \ni x\) we have \[(E \setminus \{x\}) \cap U \neq \varnothing.\]

An accumulation point \(x\) of \(E \subseteq X\) is sometimes also called a limit point of \(E\) or a cluster point of \(E\).

Definition. A point \(x \in E\) is called an isolated point of \(E\) if it is not an accumulation point of \(E\).

Definition. We say that a subset \(E\) of a metric space \((X,\rho)\) is perfect if \(E\) is closed and every point of \(E\) is its limit point.

There exists a perfect set in \(\mathbb{R}\) which contains no segment.

-

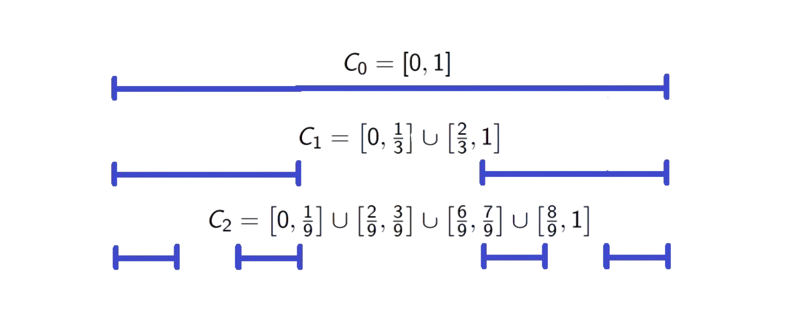

Let \(C_0=[0,1]\). Given \(C_n\) that consists of \(2^n\) disjoint closed intervals each of length \(3^{-n}\) take each of these intervals and delete the open middle third to produce two closed intervals each of length \(3^{-n-1}\).

-

Take \(C_{n+1}\) to be the union of \(2^{n+1}\) closed intervals so formed and continue.

Cantor set

Definition. The set \[\mathcal{C}=\bigcap_{n=0}^{\infty}C_n\] is called the Cantor set or ternary Cantor set.

-

Each \(C_0 \supseteq C_1 \supseteq C_2 \supseteq \ldots\) is closed and bounded thus compact, and the family \((C_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) has finite intersection property thus the Cantor set is compact and \(\mathcal{C} \neq \varnothing\) .

Property (*) By the construction for each \(k,m \in \mathbb{N}\) we see that \[\left(\frac{3k+1}{3^m},\frac{3k+2}{3^m}\right)\cap \mathcal{C}=\varnothing.\]

Properties of the Cantor set

-

Every segment \((\alpha,\beta)\) contains a segment of the form (*) if \(m\) is sufficiently large, since the set \[\left\{\frac{\ell}{3^m}: m \in \mathbb{N} \text{ and }0 \leq \ell \leq 3^{m}-1\right\}\] is dense in \([0,1]\). Thus \(\mathcal{C}\) contains no segment \((\alpha,\beta)\). This also shows that \({\rm int\;}\mathcal C=\varnothing\).

-

To prove that \(\mathcal{C}\) is perfect it is enough to show that \(\mathcal{C}\) contains no isolated points. Let \(x \in \mathcal{C}\) and let \(I_n\) be the unique interval from \(C_n\) which contains \(x \in I_n\). Let \(x_n\) be the endpoint of \(I_n\) such that \(x \neq x_n\). It follows from the construction of \(\mathcal{C}\) that \(x_n \in \mathcal{C}\). Hence \(x\) is a limit point of \(\mathcal{C}\) thus \(\mathcal{C}\) is perfect.

More about Cantor set

Cantor set has Lebesgue measure zero

-

We have \[\lambda(\mathcal C)=0.\]

Indeed, by the construction note that \[\mathcal{C}=\bigcap_{n=0}^{\infty}C_n\] and \[\lambda(C_n)=\bigg(\frac{2}{3}\bigg)^n \quad \text{ for any } \quad n\in\mathbb N.\] By the continuity of \(\lambda\), since \(C_0 \supseteq C_1 \supseteq C_2 \supseteq \ldots\) and \(\lambda(C_0)=1\), we have \[\lambda(\mathcal C)=\lim_{n\to \infty}\lambda(C_n)=\lim_{n\to \infty}\bigg(\frac{2}{3}\bigg)^n=0.\]

More about Cantor set

-

Each component of \(C_n\) can be described as the set

\[C_n=\left\{\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}\;:\; \varepsilon_j \in \{0,1,2\} \text{ and }\varepsilon_j \neq 1 \text{ for }1 \leq j \leq n\right\}.\]

-

Consequently,

\[{\color{teal}\mathcal{C}=\left\{\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}\;:\; \varepsilon_j \in \{0,2\} \right\}.}\]

Fact

Fact Any number \(\sum_{j=1}^\infty \frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}\) is uniquely determined by its sequence \(\varepsilon=(\varepsilon_j)_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\) with \(\varepsilon_j \in \{0,2\}\).

Proof. Take \(\varepsilon=(\varepsilon_j)_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\), \(\delta=(\delta_j)_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\) with \(\varepsilon_j,\delta_j \in \{0,2\}\) such that \(\varepsilon \neq \delta\). Let \(N=\min\{j \in \mathbb{N}\;:\; \varepsilon_j \neq \delta_j\}\) and assume \(0=\varepsilon_N<\delta_N=2\). Then \[\begin{aligned} \sum_{j=1}^{\infty}\frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}&= \sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}+\sum_{j=N+1}^{\infty}\frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j} \leq \sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\frac{\delta_j}{3^j}+\frac{2}{3^{N+1}}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty}\frac{1}{3^j} \\&\leq \sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\frac{\delta_j}{3^j}+\frac{2}{3^{N+1}}\underbrace{\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{3}}}_{{\color{red}\frac{3}{2}}} =\sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\frac{\delta_j}{3^j}+\frac{1}{3^N}<\sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\frac{\delta_j}{3^j}+\frac{2}{3^N}\le \sum_{j=1}^{\infty}\frac{\delta_j}{3^j}. \end{aligned}\] This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remarks.

Remark. We have two different representations \[\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{3}&=\sum_{j=1}^\infty \frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}=A, \quad \varepsilon_1=1, \quad \varepsilon_j=0 \quad\text{ for } \quad j \geq 2.\\ \frac{1}{3}&=\sum_{j=1}^\infty \frac{\varepsilon_j}{3^j}=B, \quad \varepsilon_1=0, \quad \varepsilon_j=2 \quad \text{ for } \quad j \geq 2. \end{aligned}\]

There is a bijection \(\phi:\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}} \to \mathcal{C}\) defined by \[\phi(z)=\frac{2}{3}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty}\frac{z_j}{3^j} \quad \text{ for } \quad z=(z_j)_{j \in \mathbb{N}}, \quad z_j \in \{0,1\},\] and consequently \({\rm card\;}(\mathcal{C})={\rm card\;}(\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}})={\rm card\;}(\mathbb{R})=\mathfrak{c}.\)

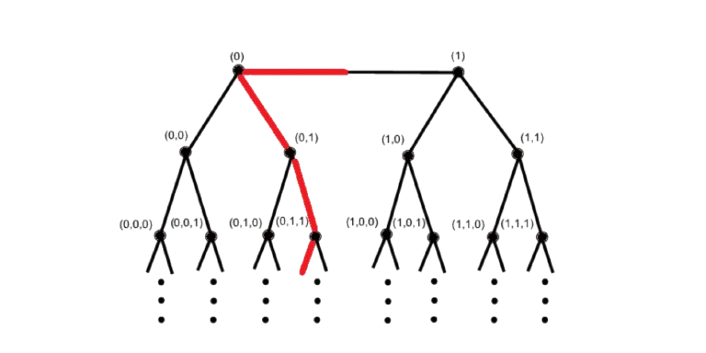

Cantor tree

\({\color{red}\varepsilon=(0,1,1,0,\varepsilon_4,\varepsilon_5,\ldots)}\)

Cantor–Lebesgue function

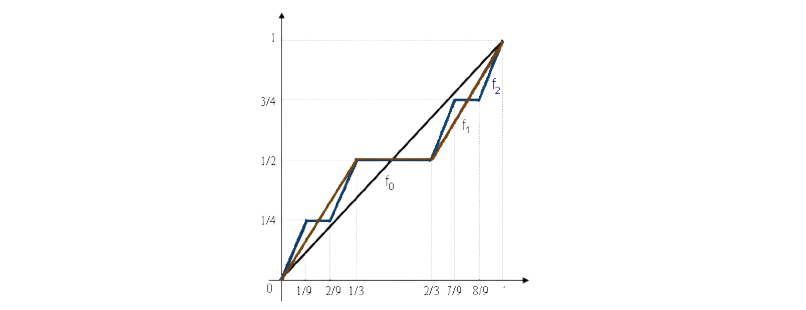

Cantor–Lebesgue approximating function For each \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) and \(x\in[0, 1]\) we define \[f_n(x)=\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^n\lambda(C_n\cap[0, x]).\]

Cantor–Lebesgue function

-

Because \(C_n\) is a finite union of intervals, \[f_n(x)=\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^n\lambda(C_n\cap[0, x]).\] is a polygonal function with \(f_n(0)=0\), \(f_n(1)=1\), and \(f_n\) is constant on each of \(2^{n}-1\) open intervals composing \([0,1] \setminus C_n\) and rises with slope \(\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^n\) on each on the \(2^n\) closed intervals composing \(C_n\).

-

If the \(j\)-th interval of \(C_n\) counting from the left is \([a_{n,j},b_{n,j}]\), then \[f_n(a_{n,j})=\frac{j-1}{2^n} \quad \text{ and } \quad f_n(b_{n,j})=\frac{j}{2^n}.\] Also \(a_{n,j}=a_{n+1, 2j-1}\) and \(b_{n, j}=b_{n+1, 2j}\) and \[f_{n+1}(a_{n, j})=f_{n}(a_{n, j}) \quad \text{ and } \quad f_{n+1}(b_{n, j})=f_{n}(b_{n, j})\] and \(f_{n+1}\) agrees with \(f_n\) at all of the endpoints of the intervals of \(C_n\) and therefore on \([0,1] \setminus C_n\).

Cantor–Lebesgue function

-

Within any particular interval \([a_{n,j},b_{n,j}]\) of \(C_n\) the greatest difference between \(f_n(x)\) and \(f_{n+1}(x)\) is at the new endpoints within that interval and the magnitude of the difference is at most \(\frac{1}{6 \cdot 2^n}\). Thus we have \[|f_{n+1}(x)-f_n(x)| \leq \frac{1}{6 \cdot 2^n} \quad \text{ for any } \quad n \in \mathbb{N}.\]

-

Since \[\frac{1}{6}\sum_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\frac{1}{2^n}<\infty.\] thus \((f_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is uniformly convergent to a continuous function \(f:[0,1] \to [0,1].\)

-

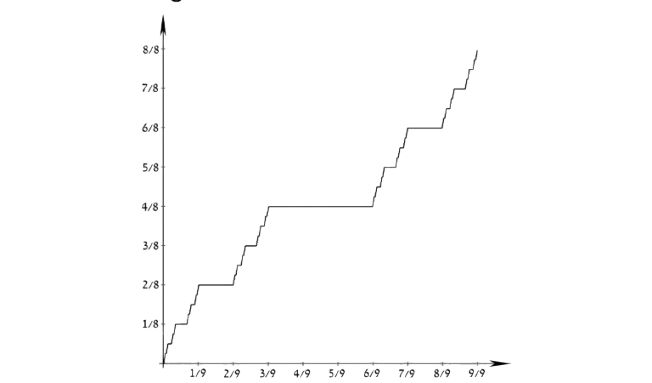

This function is called the Cantor–Lebesgue function or Devil’s staircase function.

Cantor–Lebesgue function

The Cantor–Lebesgue function or Devil’s staircase function:

Properties of the Cantor–Lebesgue function

-

Every \(f_n\) is non-decreasing so is \(f\).

-

Let \(\phi:\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}} \to \mathcal{C}\), be given by \[\phi(z)=\frac{2}{3}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty}\frac{z_j}{3^j}\] for every \(z=(z_j)_{j \in \mathbb{N}} \in \{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}}\). Then \[f(\phi(z))=\frac{1}{2}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty}\frac{z_j}{2^j}.\]

-

Indeed, fix \(\eta=\{\eta_0,\eta_1,\ldots\} \in \{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}}\) and for each \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) take \(I_n\) to be the component of \(C_n\) containing \(\phi(\eta)\). Then \(I_{n+1}\) will be the left-hand third of \(I_{n+1}\) if \(\eta_n=0\) and the right-hand third if \(\eta_n=1\).

Properties of the Cantor–Lebesgue function

-

Taking \(a_n\) to be the left-hand endpoint of \(I_n\) we see that \[a_{n+1}=a_{n}+\frac{2}{3}\cdot\frac{\eta_n}{3^{n}} \quad\text{ and }\quad f_{n+1}(a_{n+1})=f_n(a_n)+\frac{1}{2}\cdot \frac{\eta_n}{2^{n}}\] for each \(n\in\mathbb N\). Thus \[\phi(\eta)=\lim_{n \to \infty}a_n\] and \[f(\phi(z))=\lim_{n \to \infty}f_n(a_n)=\frac{1}{2}\sum_{j=0}^{\infty}\frac{\eta_j}{2^j}.\]

-

In particular, \(f[\mathcal{C}]=[0,1]\) since any \(x\in[0, 1]\) is expressible as \[x=\sum_{j=0}^{\infty}\frac{\eta_j}{2^{j+1}}=f(\phi(\eta))\] for some \(z =(z_j)_{j \in \mathbb{N}} \in \{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}}\).

The axiom of choice

The axiom of choice If \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is a nonempty collection of nonempty sets, then \[\prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha} \neq \varnothing.\]

Corollary If \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\) is a disjoint collection of nonempty sets, then there is a set \(Y \subseteq \bigcup_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha}\) (called the selector of \((X_{\alpha})_{\alpha \in A}\)) such that \(Y \cap X_{\alpha}\) contains precisely one element for each \(\alpha \in A\).

Proof.

Take \(f \in \prod_{\alpha \in A}X_{\alpha} \neq \varnothing\). Define \[Y=f[A],\] then \[Y \cap X_{\alpha}=\{f(\alpha)\}\] since \(f(\alpha) \in X_{\alpha}\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Nonmeasurable sets

Some equivalence relation

Equivalence relation. We write \(x \sim y\) iff \(x-y \in \mathbb{Q}\). This is an equivalence relation:

-

\(x \sim x\), since \(x-x=0 \in \mathbb{Q}\) for any \(x \in [0,1]\),

-

if \(x \sim y\), then \(y \sim x\),

-

if \(x \sim y\) and \(y \sim z\), then \(x \sim z\).

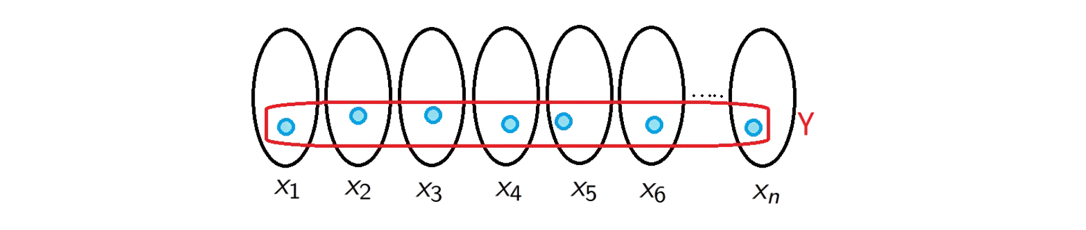

Let \(\{\epsilon_{\alpha}: \alpha\in A\}\) be the set of all equivalence classes. The equivalence classes \(\epsilon_{\alpha}\) are either disjoint or coincide, and \([0,1]\) is the disjoint union of all equivalence classes, we write \[[0,1]=\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}\epsilon_\alpha,\] and \[\epsilon_\alpha \cap \epsilon_\beta=\varnothing \quad \text{ if } \quad \alpha \neq \beta.\]

Nonmeasurable subset of \(\mathbb R\)

Vitali’s Theorem. There exists a nonmeasurable subset of \(\mathbb{R}\).

Proof. Since \([0,1]=\bigcup_{\alpha \in A}\epsilon_\alpha\), by the axiom of choice there is a selector \[\mathcal{N}=\{x_{\alpha}: \alpha \in A\}\] for the family \((\epsilon_\alpha)_{\alpha \in A}\) such that \[{\rm card\;}(\mathcal{N} \cap \epsilon_{\alpha})=1 \quad \text{ for any }\quad \alpha \in A\] We claim that the set \(\mathcal{N}\) is non-measurable.

-

Let \(\{r_k: k \in \mathbb{N}\}=\mathbb{Q} \cap [0,1]\). For each \(k \in \mathbb{N}\) consider \[\mathcal{N}_k=r_k+\mathcal{N}.\]

-

We show that

-

\(\mathcal{N}_k \cap \mathcal{N}_l = \varnothing\) if \(k \neq l\),

-

\([0,1] \subseteq \bigcup_{k=1}^{\infty}\mathcal{N}_k \subseteq [-1,2]\).

-

-

Proof of (i). If \(\mathcal{N}_k \cap \mathcal{N}_l \neq \varnothing\) for some \(l \neq k\), then there are \(\alpha,\beta\in A\) and \(r_k \neq r_l\) such that \[x_{\alpha}+r_k=x_{\beta}+r_l \iff x_{\alpha}-x_{\beta}=r_l-r_k.\] Consequently, \(\alpha \neq \beta\) and \(x_{\alpha} - x_{\beta}\in \mathbb{Q}\). Hence, \(x_{\alpha} \sim x_{\beta}\). But this contradicts the fact that \(\mathcal{N}\) contains only representative of each equivalence class.

-

Proof of (ii). Of course \(\bigcup_{k=1}^{\infty}\mathcal{N}_k \subseteq [-1,2]\). If \(x \in [0,1]\) then \(x \sim x_{\alpha}\) for some \(\alpha \in A\) and \(x-x_{\alpha}=r_k\) for some \(k \in \mathbb{N}\) thus \[x=x_\alpha+r_k \in r_k+\mathcal{N}=\mathcal{N}_k.\]

-

If we assume that \(\mathcal{N}\) is measurable then \[\begin{aligned} \lambda(\mathcal{N})=\lambda(r_k+\mathcal{N})=\lambda(\mathcal{N}_k) \quad \text{ for all } \quad k \in \mathbb{N}, \end{aligned}\] by the translation invariance of Lebesgue measure. Now note that \[\begin{aligned} 1=\lambda([0,1]) &\leq \lambda\bigg(\bigcup_{k=1}^{\infty}\mathcal{N}_k\bigg)\\ &=\sum_{k=1}^{\infty}\lambda(\mathcal{N}_k) \\ &\leq \lambda([-1,2])=3. \end{aligned}\]

-

This is a contradiction since neither \(\lambda(\mathcal{N})=0\) nor \(\lambda(\mathcal{N})=1\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$