17. Hilbert spaces PDF TEX

Inner product

Let \(H\) be a complex vector space. The inner product (or scalar product) on \(H\) is a map \[{\color{purple}H \times H\ni (x,y) \mapsto \langle x,y\rangle \in \mathbb{C}}\] such that

-

\(\langle ax+by,z\rangle=a\langle x,z \rangle+b\langle y,z\rangle\) for all \(x,y,x \in H\) and \(a,b \in \mathbb{C}\),

-

\(\overline{\langle x,y \rangle}=\langle y,x\rangle\) for all \(x,y \in H\),

-

\(\langle x,x \rangle \in (0,\infty)\) for all \(x \in H \setminus \{0\}\).

Remark. Observe that (i) and (ii) imply \[\langle x, ay+bz\rangle=\overline{a}\langle x,y\rangle +\overline{b}\langle x,z\rangle \quad \text{ for all } \quad x,y,z \in H, \quad a,b \in \mathbb{C}.\]

Pre-Hilbert space

Real inner products One can also define inner product on real vector space \(H\): \(\langle x,y\rangle\) is then real, one assumes that \(a,b \in \mathbb{R}\) in \((i)\), and (ii) becomes \(\langle x,y\rangle =\langle y,x\rangle\).

We say that a vector \(x \in H\) is orthogonal to \(y \in H\) if \[\langle x,y\rangle=0,\] and we write \(x \perp y\).

Pre-Hilbert spaces A complex vector space equipped with an inner product is called a pre-Hilbert space. If \(H\) is a pre-Hilbert space, for \(x \in H\) we define \[{\color{blue}\|x\|=\sqrt{\langle x,x \rangle}}.\]

A useful fact

Proposition (A). Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a pre-Hilbert space. For \(x, y\in H\) we have \[x\perp y \quad \iff \quad \|y\| \leq \|\lambda x+y\| \quad \text{ for all } \quad \lambda \in \mathbb{C}.\]

Proof \((\Longrightarrow)\). If \(x \perp y\) then \(\alpha=\langle x,y\rangle=0\), and \[\begin{aligned} \|\lambda x+y\|^2 &=\langle \lambda x, \lambda x\rangle+\langle \lambda x,y\rangle+\langle y,\lambda x\rangle+\langle y,y\rangle\\ &=|\lambda|^2\|x\|^2+2{\rm Re}(\alpha \lambda)+\|y\|^2. \end{aligned}\] Then we see that \(\|\lambda x+y\|^2=|\lambda|^2\|x\|^2+\|y\|^2 \geq \|y\|^2\) as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof \((\Longleftarrow)\). Let \(\alpha=\langle x,y\rangle\) as before. If \(x =0\) then the claim is obvious. If \(x \neq 0\) take \({\color{blue}\lambda=-\frac{\overline{\alpha}}{\|x\|^2}}\), and by the previous calculation, we have \[\begin{aligned} \|y\|^2\le\|\lambda x+y\|^2=|\lambda|^2\|x\|^2+2{\rm Re}(\alpha \lambda)+\|y\|^2=\|y\|^2-\frac{|\alpha|^2}{\|x\|^2}, \end{aligned}\] which implies that \(\alpha=\langle x,y\rangle=0\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Cauchy–Schwarz inequality

Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a pre-Hilbert space. For all \(x,y \in H\) we have \[|\langle x,y\rangle| \leq \|x\|\|y\|\] with equality iff \(x,y\) are linearly dependent.

Proof. If \(\langle x,y\rangle=0\) the result is obvious. If \(\langle x,y\rangle \neq 0\), let \(\alpha=\langle x,y\rangle\), and using calculations from the previous proposition with \({\color{blue}\lambda=-\frac{\overline{\alpha}}{\|x\|^2}}\) we obtain \[\begin{aligned} 0 \leq \|\lambda x+y\|^2 &=|\lambda|^2\|x\|^2+2{\rm Re}(\alpha \lambda)+\|y\|^2\\ &=\|y\|^2-\frac{|\alpha|^2}{\|x\|^2}. \end{aligned}\] Then \[\qquad\qquad |\langle x,y\rangle| \leq \|x\|\|y\|. \qquad\qquad\tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Continuity of scalar products

Proposition (B). Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a pre-Hilbert space. If \(x_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n\to \infty}} \ x\), \(y_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n\to \infty}} \ y\) in \(H\), then \[\langle x_n,y_n\rangle \ _{\overrightarrow{n\to \infty}} \ \langle x,y\rangle.\]

Proof. By the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality \[\begin{aligned} \qquad |\langle x,y\rangle-\langle x_n,y_n\rangle| &\leq {\color{red}|\langle x_n-x,y_n\rangle|}+{\color{blue}|\langle x,y_n-y\rangle|}\\ &\leq {\color{red}\|x-x_n\|\|y_n\|}+{\color{blue}\|x\|\|y-y_n\|} \ _{\overrightarrow{n\to \infty}} \ 0. \qquad {\blacksquare} \end{aligned}\]

Pre-Hilbert spaces and Hilbert spaces

Proposition. Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a pre-Hilbert space. The function \({\color{red} H\ni x \mapsto \|x\|\in [0, \infty)}\) is a norm on \(H\).

Proof. \(\|x\|=0\) iff \(x=0\) and \(\|\lambda x\|=|\lambda|\|x\|\). By the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality we obtain Minkowski’s inequality inequality \[\begin{aligned} \qquad \|x+y\|^2&=\langle x+y,x+y\rangle\\ &=\|x\|^2+2{\rm Re}(\langle x,y\rangle)+\|y\|^2\\ &\leq \|x\|^2+2\|x\|\|y\|+\|y\|^2=(\|x\|+\|y\|)^2.\qquad {\blacksquare} \end{aligned}\]

A pre-Hilbert space \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) that is complete with respect to the norm is called a Hilbert space. Here \(\|x\|=\sqrt{\langle x, x\rangle}\) for all \(x\in H\).

Hilbert spaces

Examples.

-

\(H=\mathbb{C}^d\) is a finite dimensional Hilbert space, with the scalar product

\[\langle x,y\rangle=\sum_{j=1}^dx_j \overline{y_j}.\]

-

Let \(A\) be a countable set. Then \(H=\ell^2(A)\) is a Hilbert space, with the scalar product

\[\langle x,y\rangle=\sum_{j \in A}x_j \overline{y_j}.\]

-

Let \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) be a measure space. Then \(H=L^2(X)\), is a Hilbert space, with the scalar product \[\langle f,g\rangle=\int_X f(x)\overline{g(x)}d\mu(x).\]

The Parallelogram Law

Proposition (The Parallelogram Law). Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a pre-Hilbert space. For all \(x,y \in H\) we have \[\|x+y\|^2+\|x-y\|^2=2(\|x\|^2+\|y\|^2).\]

Proof. Observe that \[\|x \pm y\|^2=\|x\|^2\pm 2{\rm Re}(\langle x,y\rangle)+\|y\|^2.\] Add these two formulas and we are done. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Spaces with Parallelogram Law are Hilbert spaces

If \(H\) is a normed vector space which satisfies the Parallelogram Law then there exists a unique inner product that gives rise to the norm.

Proof. If \(H\) is a real vector space the inner product is defined by \[\langle x,y\rangle=\frac{1}{4}\left(\|x+y\|^2-\|x-y\|^2\right).\] If \(H\) is a complex normed space the inner product is defined by \[\langle x,y\rangle=\frac{1}{4}\left(\|x+y\|^2-\|x-y\|^2+i\|x+iy\|^2-i\|x-iy\|^2\right).\]

The Pythagorean Theorem

Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a pre-Hilbert space. If \(E \subseteq H\) we define \[E^{\perp}=\{x \in H: \langle x,y\rangle=0 \text{ for all }y \in E\}.\] It is easy to see by Proposition (B) that \(E^{\perp}\) is a closed subspace of \(H\).

Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a pre-Hilbert space. If \(x_1,\ldots,x_n \in H\) are \(x_j \perp x_k\) for all \(j \neq k\), then \[\bigg\|\sum_{j=1}^nx_j\bigg\|^2=\sum_{j=1}^n\|x_j\|^2.\]

Proof. We have \[\begin{aligned} \qquad \qquad \bigg\|\sum_{j=1}^nx_j\bigg\|^2 &=\bigg\langle \sum_{j=1}^nx_j,\sum_{j=1}^nx_j\bigg\rangle\\ &=\sum_{j=1}^n\sum_{k=1}^n\langle x_j,x_k\rangle\\ &=\sum_{j=1}^{n}\langle x_j,x_j\rangle +\sum_{j \neq k}\underbrace{\langle x_k,x_j\rangle}_{=0}\\ &=\sum_{j=1}^n\|x_j\|^2.\qquad \qquad {\blacksquare} \end{aligned}\]

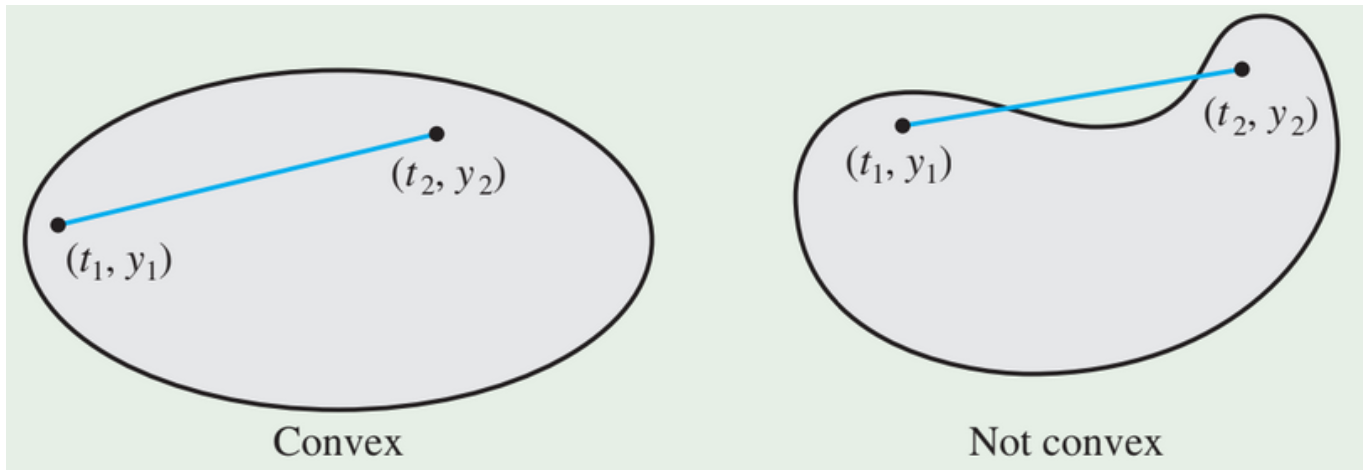

Convex sets

We say that \(E \subseteq H\) is convex if for every \(x,y \in E\) and \(\lambda \in [0,1]\) we have \[\lambda x+(1-\lambda)y \in E.\]

Best approximation result

Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a Hilbert space. Every non-empty closed convex set \(E \subseteq H\) contains a unique \(x\) of minimal norm.

Proof. Set \(d=\inf\{\|x\|:x \in E\}\), and take a sequence \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\subseteq E\) such that \(\|x_n\| \ _{\overrightarrow{n\to \infty}} \ d\). Then by convexity \[\frac{1}{2}\left(x_n+x_m\right) \in E,\] which implies that \(\|x_n+x_m\|^2 \geq 4d^2\) and by the parallelogram law we have \[\|x_n-x_m\|^2=2\|x_n\|^2+2\|x_m\|^2-\|x_n+x_m\|^2 \leq 2\|x_n\|^2+2\|x_m\|^2-4d^2 \ _{\overrightarrow{m, n\to \infty}} \ 0.\] So \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is a Cauchy sequence in \(H\) and \(E\) is closed, so it converges to some \(x \in E\) with \(\|x\|=d.\) Moreover, \(x \in E\) is unique. Show this! $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Closed subspaces in Hilbert spaces are complemented

Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a Hilbert space. If \(M\) is a closed subspace of \(H\), then \[H=M \oplus M^{\perp} \quad \text{ and } \quad M \cap M^\perp=\{0\}.\] \(M^{\perp}\) is also closed and it is called the orthogonal complement of \(M\).

Proof. If \(x \in M\cap M^\perp\), then \(\langle x,x\rangle=0\), and \(x=0\), hence \(M \cap M^\perp=\{0\}\). If \(x \in H\) we apply (BAT) to the set \(x-M\), which is convex and closed and find \({\color{red}P_Mx \in M}\) such that \(\|x-P_Mx\|\) is minimal. Set \(z=x-P_Mx\), then \[\|z\|=\|x-P_Mx\| \leq \|x-(P_Mx+\lambda y)\|=\|z+\lambda y\|\] for all \(\lambda \in \mathbb{C}\) and \(y \in M\), thus \(z \perp y\) for any \(y \in M\) (by Proposition (A)) hence \(z \in M^\perp\). Since \(x=P_Mx+z\) we have \(H \subseteq M \oplus M^\perp\), which gives \(H=M \oplus M^\perp\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Corollary

Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a Hilbert space. If \(M\) is a closed subspace of \(H\), then \[(M^\perp)^\perp=M.\]

Proof. Take \(x \in M\), then \(\langle x,y\rangle=0\) for all \(y \in M^\perp\). But \[(M^\perp)^\perp=\{x \in H: \langle x,y\rangle=0 \ \text{ for all }\ y \in M^\perp\},\] thus \(M \subseteq (M^\perp)^\perp\). Moreover, \[M \oplus M^\perp =H=M^\perp \oplus (M^\perp)^\perp,\] so by the uniqueness of these decompositions \(M\) cannot be a proper subspace of \((M^\perp)^\perp\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Projections

Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a Hilbert space and \(M \subseteq H\) be its closed subspace. For every vector \(x \in H\) we define its projection \(P_Mx\) onto \(M\) as the unique element of \(M\) with the property that \[x-P_Mx \perp M \quad \text{ and } \quad \|x-P_Mx\|\quad \text{ is minimal.}\]

Proposition (C). Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a Hilbert space with a closed subspace \(M \subseteq H\). If a map \(P_M:H \to H\) is defined by \(P_M(x)=P_Mx\) for all \(x \in H\), then \(P_M\) defines a linear projection with \(\|P_M\|=1\).

Proof. To prove linearity, let \(x,y \in H\), \(\alpha,\beta \in \mathbb{C}\) and \(z \in M\). Then \[\begin{aligned} &\langle \alpha x+\beta y-(\alpha P_M x+\beta P_My),z\rangle\\ &=\alpha \langle x-P_Mx,z\rangle+\beta \langle y-P_My,z\rangle=0. \end{aligned}\]

Thus \(\alpha P_M x +\beta P_M y \in M\) and \(\alpha x+\beta y-(\alpha P_M x+\beta P_My) \perp M\). But \(P_M(\alpha x+\beta y)\) is the unique element with this property, so \[P_M(\alpha x+\beta y)=\alpha P_Mx+\beta P_M y.\]

For the second part, let \(x \in H\) and \(P_M x \in M\), so \(x-P_Mx \perp P_Mx\). Then by the Pythagorean theorem \[\|x\|^2=\|P_M x\|^2+\|x-P_Mx\|^2 \geq \|P_Mx\|^2,\] hence \(\|P_M x\| \leq \|x\|\), and \[\|P_M\|=\sup_{\|x\|=1}\|P_M x\|=\sup_{\|x\| \leq 1}\|P_Mx\|\le 1.\] If \(x \in M\), then \(P_Mx=x\), so \(\|P_M\|=1\). This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Riesz representation theorem

Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a Hilbert space. If \(\Lambda \in H^*\) then there is \(y \in H\) such that \({\color{red}\Lambda x=\langle x,y\rangle}\) for all \(x \in H\). Moreover, we have \(\|\Lambda\|_{H^{*}}=\|y\|.\)

Remark.

-

The significance of this theorem is the identification of \(H^{*}\) with \(H\). If \(H\) is a real Hilbert space, then \(H^{*}\) and \(H\) are isometrically isomorphic.

-

If \(H\) is complex, it remains an isometry, but the correspondence is given by what is sometimes called a conjugate isomorphism. Specifically, if \(\varphi, \psi\in H^*\) correspond to \(u, v\in H\) (respectively), then \(\alpha\varphi+ \beta\psi\) corresponds to \(\alpha u + \beta v\). Sometimes this is called conjugate linearity or anti-isomorphism.

-

Regardless of the underlying scalar field (real or complex), a consequence of the identification of \(H\) with \(H^*\) is that any Hilbert space is reflexive.

Proof of uniqueness. Suppose that there are two \(y, y'\in H\) such that \(\Lambda(x)=\langle x,y\rangle =\langle x,y' \rangle\), then \[\langle x,y-y'\rangle=0 \quad \text{ for all } \quad x \in H.\] Thus \[\|y-y'\|^2 =0, \quad \text{ so } \quad y=y'.\]

Proof of the existence. We first show that \(\|\Lambda\|_{H^{*}}=\|y\|\). If \(y \in H\) and \(\Lambda x=\langle x,y\rangle\) for all \(x \in H\), then \[\|y\|^2=\langle y,y\rangle=\Lambda y \leq \|\Lambda\|_{H^{*}}\|y\|,\] so \(\|y\| \leq \|\Lambda\|_{H^{*}}\). By the Cauchy–Schwarz we always have \(|\Lambda x| \leq \|x\|\|y\|\) hence \(\|\Lambda\|_{H^{*}} \leq \|y\|\) and consequently \(\|\Lambda\|_{H^{*}}=\|y\|\).

Finally, we find \(y\in H\) such that \(\Lambda x=\langle x,y\rangle\) for all \(x \in H\). If \(\Lambda=0\) take \(y=0\). If \(\Lambda \neq 0\) let \[{\rm ker}\Lambda=\{h \in H: \Lambda h=0\}.\]

Since \({\rm ker}\Lambda\) is closed, we may write \[H=({\rm ker}\Lambda) \oplus ({\rm ker}\Lambda)^{\perp}\]

and \(\Lambda \neq 0\) so there is \(z \neq 0\) and \(z \in ({\rm ker}\Lambda)^\perp\). We have \[(\Lambda x)z-(\Lambda z)x \in {\rm ker}\Lambda \quad \text{ for any } \quad x \in H,\] hence \((\Lambda x)z-(\Lambda z)x \perp z\), and \[\Lambda x\langle z,z\rangle=\Lambda z \langle x,z\rangle \quad \text{ for any }\quad x \in H.\] Then we see \[\Lambda x=\bigg\langle x,\frac{(\overline{\Lambda z})z}{\langle z,z\rangle}\bigg\rangle.\]

It suffices to take \[{\color{blue}y=\frac{(\overline{\Lambda z})z}{\|z\|^2}}\] and we are done.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Orthonormal set and the Gram–Schmidt process

A subset \(\{u_{\alpha}:{\alpha \in A}\}\) of \(H\) is called orthonormal iff \(\|u_{\alpha}\|=1\) for all \(\alpha \in A\) and \(u_\alpha \perp u_\beta\) whenever \(\alpha \neq \beta\).

Remark. If \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is a linearly independent sequence in \(H\) there is a standard inductive procedure, called the Gram–Schmidt process for converging \((x_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) into an orthonormal sequence \((u_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) such that \[{\color{red}{\rm span} \{x_1,\ldots,x_n\}={\rm span} \{u_1,\ldots,u_n\} \quad \text{ for each } \quad n\in\mathbb N,}\] and \[{\color{blue}u_i \perp u_j \quad \text{ for } \quad i \neq j \quad \text{ and }\quad 1\leq i,j \leq n}.\]

Gram–Schmidt algorithm

Step 1. Take \(u_1=\frac{x_1}{\|x_1\|}\).

Step 2. Having defined \(u_1,u_2,\ldots,u_{N-1}\) we set \[{\color{blue}v_N=x_N-\sum_{j=1}^{N-1} \langle x_N,u_j\rangle u_j}.\] Then \(v_N \neq 0\) since \(x_N \not\in {\rm span}\{x_1,\ldots,x_{N-1}\}={\rm span} \{u_1,\ldots,u_{N-1}\}\) and for every \(1\le m\le N-1\) we have \[\begin{aligned} \langle v_N,u_m\rangle&=\langle x_N,u_m \rangle-\sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\langle x_N,u_j\rangle \langle u_j,u_m\rangle\\&=\langle x_N,u_m\rangle-\langle x_N,u_m\rangle \langle u_m,u_m\rangle=0 \end{aligned}\] since \(\langle u_m,u_m\rangle=1\). We can thus take \[{\color{blue}u_N=\frac{v_N}{\|v_N\|}}.\]

Bessel’s inequality

Let \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) be a pre-Hilbert space. If \(\{u_\alpha:{\alpha \in A}\}\) is an orthonormal system in \(H\), then for any \(x \in H\) we have \[\sum_{\alpha \in A}|\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle|^2 \leq \|x\|^2.\]

In particular, the set \[\{\alpha \in A: \langle x,u_\alpha\rangle \neq 0\}\] is countable.

Convention \[\sum_{x \in X}f(x)=\sup\Big\{\sum_{x \in F}f(x): F \subseteq X, \ \ \#F<\infty\Big\}.\]

Proof. It suffices to show \[\sum_{\alpha \in F}|\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle|^2 \leq \|x\|^2\] for any finite \(F \subseteq X\). We have \[\begin{aligned} \sum_{\alpha \in F}|\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle|^2&= \sum_{\alpha \in F}\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle \overline{\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle}\\ &=\sum_{\alpha \in F}\langle x,\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle u_\alpha \rangle\\ &=\Big\langle x,\sum_{\alpha \in F}\langle x, u_\alpha\rangle u_\alpha \Big\rangle\\ &\le \|x\|\Big\|\sum_{\alpha \in F}\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle u_\alpha\Big\|, \end{aligned}\] where in the last line we have used the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.

Moreover, since \(u_{\alpha}\perp u_{\beta}\) we obtain \[\begin{aligned} \Big\|\sum_{\alpha \in F}\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle u_\alpha\Big\| &=\bigg(\sum_{\alpha,\beta \in F}\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle\langle u_\alpha,u_\beta\rangle \overline{\langle x,u_\beta\rangle}\bigg)^{1/2}\\ &=\Big(\sum_{\alpha \in F}|\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle|^2\Big)^{1/2}. \end{aligned}\] Hence \[\sum_{\alpha \in F}|\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle|^2 \leq \|x\|\Big(\sum_{\alpha \in F}|\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle|^2\Big)^{1/2}\] and we are done since \[\qquad \Big(\sum_{\alpha \in F}|\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle|^2\Big)^{1/2} \leq \|x\|.\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Orthonormal bases in Hilbert spaces

If \(\{u_\alpha:{\alpha \in A}\}\) is an orthonormal set in a Hilbert space \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) the following are equivalent:

-

Completeness: If \(\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle=0\) for all \(\alpha \in A\), then \(x=0\).

-

Parseval’s identity: \[\|x\|^2=\sum_{\alpha \in A}|\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle|^2 \quad \text{ for all } \quad x\in H.\]

-

For each \(x \in H\) we have \[x=\sum_{\alpha \in A}\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle u_\alpha,\] where the sum has only countably non-zero terms and converges in the norm topology no matters how these terms are ordered.

Proof (a)\(\implies\)(c). If \(x \in H\) let \(\alpha_1,\alpha_2,\ldots,\alpha_n\) be enumeration of the \(\alpha\)’s for which \(\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle \neq 0\). By Bessel’s inequality, we have \[\sum_{j \in \mathbb{N}}|\langle x,u_{\alpha_j}\rangle|^2 \leq \|x\|^2,\] thus the series converges. By the Pythagorean theorem \[\begin{aligned} \Big\|\sum_{j=m}^n \langle x,u_{\alpha_j}\rangle u_{\alpha_j}\Big\|^2 =\sum_{j=m}^n |\langle x,u_{\alpha_j}\rangle|^2 \ _{\overrightarrow{m, n\to \infty}} \ 0 \end{aligned}\] so the sum \(\sum_{j=1}^n \langle x,u_{\alpha_j}\rangle u_{\alpha_j}\) converges, since \(H\) is complete.

Now if \[y=x-\sum_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\langle x,u_{\alpha_j}\rangle u_{\alpha_j}\] clearly \(\langle y,u_{\alpha_j}\rangle=0\) for all \(\alpha \in A\) so by (a) we have \(y=0\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Proof (c)\(\implies\)(b). Take \(F \subseteq A\) countable such that \[x=\sum_{\alpha \in F}\langle x,u_{\alpha}\rangle u_\alpha,\] then \[\qquad\qquad\sum_{\alpha \in F}|\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle|^2 =\Big\langle x,\sum_{\alpha \in F}\langle x,u_{\alpha}\rangle u_\alpha\Big\rangle=\|x\|^2.\qquad\qquad\tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Proof (b)\(\implies\)(a). If \(\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle=0\) for all \(\alpha \in A\) then \(\|x\|=0\), since \[\qquad\qquad \|x\|^2=\sum_{\alpha \in A}|\langle x,u_\alpha\rangle|^2=0. \qquad\qquad\tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

An orthonormal set having the properties (a)-(c) is the previous theorem is called an orthonormal basis for \(H\).

Orthonormal bases always exist for Hilbert spaces

Example. Let \(H=\ell^2(A)\). For each \(\alpha \in A\) define \[e_\alpha(\beta)= \begin{cases} 1 &\text{ if }\alpha=\beta,\\ 0 & \text{ otherwise.} \end{cases}\] The set \(\{e_\alpha:{\alpha \in A}\}\) is an orthonormal basis for \(\ell^2(A)\) and \(\langle f,e_\alpha \rangle=f(\alpha)\) for any \(f \in \ell^2(A)\).

Every Hilbert space \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) has an orthonormal basis.

Proof. By Kuratowski–Zorn’s lemma the collection of all orthonormal sets ordered by inclusion has a maximal element and maximality is equivalent to the completeness property from item (a) of the previous teorem.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Orthogonal projections

Proposition (Orthogonal projections). Let \(M\) be a closed subset of a Hilbert space \((H, \|\cdot\|)\). Suppose that a set \(\{u_1,\ldots,u_N\}\) is an orthonormal basis for \(M\), where \(N \in \mathbb{N} \cup\{\infty\}\). For any \(x \in H\) its orthogonal projection can be written by \[P_Mx=\sum_{n=1}^N \langle x,u_n\rangle u_n.\]

Proof. \(P_M x \in M\) and \(x-P_M x \perp M\). Thus \[\begin{aligned} P_Mx=\sum_{n=1}^N \langle P_Mx,u_n\rangle u_n=\sum_{n=1}^N \langle P_Mx-x,u_n\rangle u_n+\sum_{n=1}^N \langle x,u_n\rangle u_n. \quad {\blacksquare} \end{aligned}\]

Separable Hilbert spaces

A Hilbert space \((H, \|\cdot\|)\) is separable iff it has a countable orthogonal basis, in which case every orthonormal basis for \(H\) is countable.

Proof (\(\Longrightarrow\)). If \(\{x_n: n \in \mathbb{N}\}\) is a dense set in \(H\), then by discarding inductively any \(x_n\) that is in a linear span of \(x_1,\ldots,x_{n-1}\) we obtain a linearly independent sequence \(\{y_n: n \in \mathbb{N}\}\) whose linear span is dense in \(H\). Application of the Gram–Schmidt process to \(\{y_n:n \in \mathbb{N}\}\) yields an orthonormal sequence \(\{u_n: n \in \mathbb{N}\}\) whose linear span is dense in \(H\) and which is therefore a basis.

Proof (\(\Longleftarrow\)). If \(\{u_n: n \in \mathbb{N}\}\) is a countable orthonormal basis in \(H\) the finite linear combinations of the \(u_n\)’s with coefficients in a countable dense subset of \(\mathbb{C}\) form a countable dense set in \(H\). If \(\{v_\alpha: \alpha \in A\}\) is another orthonormal basis, for each \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) the set \(A_n=\{\alpha \in A: \langle u_{n},v_\alpha\rangle \neq 0\}\) is countable. By completeness of \(\{u_n:{n \in \mathbb{N}}\}\), the set \(A=\bigcup_{n \in \mathbb{N}}A_n\) is also countable.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Fourier basis

The set \({\color{purple}\{e^{2\pi i n x}: n \in \mathbb{Z}\}}\), which is called the standard Fourier basis, is an orthonormal basis in \(L^2([0,1])\). We have \[\langle e^{2\pi i nx},e^{2\pi i m x}\rangle =\int_0^1 e^{2\pi i (n-m) x}dx=\begin{cases} 1 &\text{ if }n=m,\\ 0 &\text{ otherwise.} \end{cases}\] By the Weierstrass theorem every continuous function on \([0,1]\) can be uniformly approximated by trigonometric polynomials. In other words, \(\overline{\mathcal{P}}^{\|\cdot\|_{\infty}}=C([0,1])\), where \[\mathcal{P}=\Big\{P(x)=\sum_{n=-N}^N a_n e^{2\pi i n x}: N \in \mathbb{N} \text{ and }a_{-N},\ldots,a_{N} \in \mathbb{C}\Big\}.\] Thus \(\overline{\mathcal{P}}^{\|\cdot\|_{L^2}}=L^2([0,1]),\) which proves, by the previous theorem, that \({\color{purple}\{e^{2\pi i n x}: n \in \mathbb{Z}\}}\) is an orthonormal basis in \(L^2([0,1])\).

Applications

Consider \(f(x)=x\) on \([0,1]\), then \[\langle f,1\rangle=\int_0^1 xdx=\frac{1}{2},\] and \[\begin{aligned} \langle f,e^{2\pi i n x}\rangle&=\int_0^1 xe^{-2\pi i n x}dx \\ &=\int_0^1 x \left(\frac{e^{-2 \pi i n x}}{-2\pi i n}\right)'dx\\ &=-\frac{1}{2\pi i n}+\frac{1}{2 \pi i n}\int_0^{1}e^{-2\pi i n x}dx\\ &=-\frac{1}{2 \pi i n}+\frac{1}{2 \pi i n} \cdot 0=\frac{i}{2 \pi n}. \end{aligned}\]

Example - application

By Parseval’s identity we have \[\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{3}=\|f\|_{L^2}^2&=\sum_{n \in \mathbb{N}}|\langle f,e^{2\pi i n x}\rangle|^2\\ &=\frac{1}{4}+\sum_{n \in \mathbb{Z} \setminus \{0\}}\frac{1}{4\pi^2 n^2}. \end{aligned}\] Hence \[\frac{1}{3}=\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{2\pi^2}\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n^2},\] and finally we conclude \[{\color{blue}\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n^2}=\frac{\pi^2}{6}}.\]