21. Hardy—Littlewood maximal function , Lebesgue differentiation theorem PDF TEX

Hardy–Littlewood maximal function

Vitali’s covering lemma

Let \((X,\mathcal M)=(\mathbb{R}^d,{\rm Bor}({\mathbb{R}^d}))\), and let \(\lambda_d\) be Lebesgue measure on \(\mathbb R^d\).

Let \(\mathcal C\) be a collection of open balls in \(\mathbb{R}^d\) and let \[U=\bigcup_{B \in \mathcal C}B.\] If \(\lambda_d(U)>c\), then there exist disjoint balls \(B_1,\ldots,B_n \in \mathcal C\) such that \[c<3^d \sum_{j=1}^n \lambda_d(B_j).\]

Proof. If \(c<\lambda_d(U)\) then from the inner regularity of Lebesgue measure \(\lambda_d\), there is a compact set \(K \subseteq U\) with \(\lambda_d(K)>c\) and finitely many balls \(A_1,\ldots,A_m\in \mathcal C\) covering \(K\), i.e. \(K\subseteq\bigcup_{j=1}^mA_j.\)

-

Let \(B_1\) be the largest of the \(A_j\)’s (the one having maximal radius).

-

Let \(B_2\) be the largest of the \(A_j\)’s that is disjoint from \(B_1\).

-

Let \(B_3\) be the largest of \(A_j\)’s that is disjoint from \(B_1\) and \(B_2\) and so on until list of \(A_j\)’s is exhausted.

-

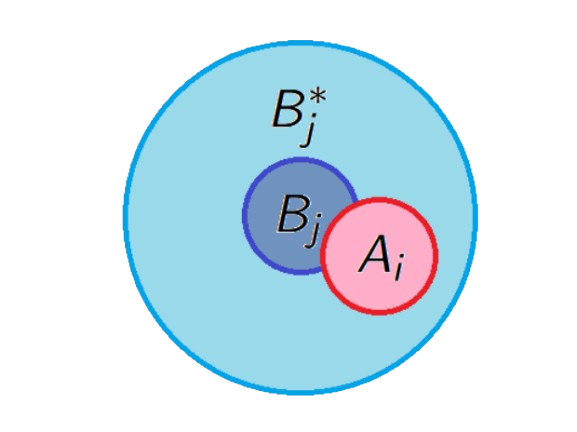

According to this construction, if \(A_i\) is not one of the \(B_j\)’s there is a \(j \in \{1,\ldots,k\}\) such that \(A_i \cap B_j \not=\varnothing\) and if \(j\) is the smallest integer with this property the radius of \(A_i\) is at most that of \(B_j\).

-

Hence \[{\color{red}A_i \subseteq B_j^{*}},\] where \(B_j^*\) is the ball concentric with \(B_j\) whose radius is three times that of \(B_j\). In other words, \({\color{red}B_j^*=3B_j}\).

-

But then \[K\subseteq\bigcup_{j=1}^mA_j \subseteq \bigcup_{j=1}^kB_j^*,\] and consequently \[c<\lambda_d(K) \leq \sum_{j=1}^k \lambda_d(B_j^*)=\sum_{j=1}^k \lambda_d(3B_j)=3^d \sum_{j=1}^k \lambda_d(B_j). \qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Locally integrable function

A measurable function \(f:\mathbb{R}^d \to \mathbb{C}\) is called locally integrable (with respect to Lebesgue measure) if \[\int_K |f(x)|\,dx<\infty\] for any bounded measurable set \(K \subseteq \mathbb{R}^d\).

Notation

-

We shall abbreviate \(d\lambda_d(x)\) to \(dx\).

-

We denote the space of locally integrable functions by \(L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb{R}^d)\).

Hardy–Littlewood averaging operator

If \(f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb{R}^d)\), \(x \in \mathbb{R}^d\) and \(r>0\) we define \(M_rf(x)\) to be the average of \(f\) over the open ball \(B(x,r)=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^d: |x-y|<r\}\), i.e. \[M_rf(x)=\frac{1}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}\int_{B(x,r)}f(y)\,dy.\]

If \(f \in L^1_{{}\rm loc}(\mathbb{R}^d)\), then \(M_rf(x)\) is jointly continuous in \((x,r) \in \mathbb{R}^d \times (0,\infty)\).

Proof. We know \(\lambda_d(B(x,r))=cr^d\), where \(c=\lambda_d(B(0,1))\) (from polar coordinates) and \(\lambda_d(S(x,r))=0\), where \(S(x,r)=\{y \in \mathbb{R}^d: |x-y|=r\}.\) Moreover, \[\lim_{\substack{r\to r_0\\x\to x_0}}\mathbf{1}_{{B(x,r)}} =\mathbf{1}_{{B(x_0,r_0)}} \quad \text{ pointwise in } \quad \mathbb{R}^d \setminus S(x_0,r_0).\]

If \(r<r_0+\frac{1}{2}\) and \(|x-x_0|<\frac{1}{2}\), note that \[\mathbf{1}_{{B(x,r)}}(y) \leq \mathbf{1}_{{B(x_0,r+1)}}(y).\] Indeed, if \(|x-y|<r\), then \[|y-x_0| \leq |x-y|+|x-x_0| \leq r+\frac{1}{2} < r_0+1.\] By the (DCT) it follows \[\lim_{\substack{r\to r_0\\x\to x_0}}\int_{B(x,r)}f(y)\,dy=\int_{B(x_0,r_0)}f(x)\,dy.\] Hence \[\qquad\qquad \lim_{\substack{r\to r_0\\x\to x_0}}M_rf(x)=M_{r_0}f(x_0). \qquad\qquad \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Hardy–Littlewood maximal function

If \(f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb{R}^d)\) we define its Hardy–Littlewood maximal function by \[M_*f(x)=\sup_{r>0}M_r|f|(x)=\sup_{r>0}\frac{1}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}\int_{B(x,r)}|f(y)|\,dy, \quad x\in \mathbb R^d.\]

Observation. For any \(\alpha>0\) we have \[\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_*f(x)>\alpha\} =\bigcup_{r>0}\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_r|f|(x)>\alpha\}.\] Thus by Lemma (A) we have that \[\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_*f(x)>\alpha\}\] is open in \(\mathbb{R}^d\).

Hardy–Littlewood maximal theorem

Fix \(d\in \mathbb N.\) Let \[M_*f(x)=\sup_{r>0}\frac{1}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}\int_{B(x,r)}|f(y)|\,dy, \quad x\in \mathbb R^d, \quad f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb{R}^d)\] be the Hardy–Littlewood maximal function. There exists a constant \(C>0\) such that for all \(f \in L^1(\mathbb{R}^d)\) and for all \(\alpha>0\) we have \[\lambda_d(\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_*f(x)>\alpha\}) \leq \frac{C}{\alpha}\int_{\mathbb{R}^d}|f(y)|\,dy=\frac{C}{\alpha}\|f\|_{L^1(\mathbb R^d)}.\] This inequality is often called in the literature the weak type \((1,1)\) inequality for the Hardy–Littlewood maximal function.

Proof. Define \[E_\alpha=\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_*f(x)>\alpha\} \quad \text{ for } \quad \alpha>0,\] this set is open according to the previous observation.

-

For each \(x \in E_{\alpha}\) we can choose \(r_{x}>0\) such that \({\color{blue}M_{r_x}|f|(x)>\alpha}\).

-

The balls \(B(x, r_x)\subseteq E_\alpha\) and \(E_\alpha\subseteq \bigcup_{x\in E_\alpha}B(x, r_x)\).

-

By Vitali’s covering lemma if \(c<\lambda_d(E_{\alpha})\) there exist \(x_1,\ldots,x_k \in E_\alpha\) such that the balls \({\color{red}B_j=B(x_j,r_{x_j})}\) are disjoint and \[c<3^d \sum_{j=1}^k \lambda_d(B_j).\]

-

Then, since \({\color{blue}\lambda_d(B_j) \leq \frac{1}{\alpha}\int_{B_j} |f(y)|\,dy}\), we obtain \[c<3^d\sum_{j=1}^k \lambda_d(B_j) \leq \frac{3^d}{\alpha}\sum_{j=1}^k\int_{B_j}|f(y)|\,dy \leq \frac{3^d}{\alpha}\int_{\mathbb{R}^d}|f(y)|\,dy.\]

-

Letting \(c \to \lambda_d(E_{\alpha})\) we obtain the claim.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Layer-cake decomposition for \(L^p\) norms

\(L^p\) norms. Let \((X,\mathcal M, \mu)\) be measure space. Recall that for \(0< p<\infty\) we have \[\|f\|_{L^p(X)}=\left(\int_{X}|f(y)|^p\,d\mu(x)\right)^{1/p}\] and for \(p=\infty\) we have \[\|f\|_{L^\infty(X)}={\rm ess.sup}_{x\in X}|f(x)|.\]

Proposition (Layer-cake decomposition). Let \((X,\mathcal M, \mu)\) be a \(\sigma\)-finite measure space. Then, for \(f \in L^p(X)\) with \(0 < p < \infty\), we have \[\|f\|_{L^p(X)}^p = p\int_0^\infty \alpha^{p-1} \mu(\{x \in X: |f(x)| > \alpha\}) d\alpha.\]

Proof. Using the Fubini-Tonelli theorem, we have \[\begin{aligned} p \int_0^\infty \alpha^{p-1} &\mu(\{x \in X: |f(x)| > \alpha\}) d\alpha \\ &= p \int_0^\infty \alpha^{p-1} \int_X \mathbf{1}_{{\{x \in X: |f(x)| > \alpha\}}} d\mu(x) d\alpha\\ &= \int_X \int_0^{|f(x)|} p\alpha^{p-1} d\alpha d\mu(x)\\ &= \int_X |f(x)|^p d\mu(x) \\ &= \|f\|_{L^p(\mathbb R^d)}^p. \end{aligned}\] This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Hardy–Littlewood maximal theorem on \(L^p\) spaces

Fix \(d\in \mathbb N\). Let \[M_*f(x)=\sup_{r>0}\frac{1}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}\int_{B(x,r)}|f(y)|\,dy, \quad x\in \mathbb R^d, \quad f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb{R}^d)\] be the Hardy–Littlewood maximal function. For every \(1<p\le \infty\), there exists a constant \(C>0\) such that for all \(f \in L^p(\mathbb{R}^d)\) we have \[\|M_*f\|_{L^p(\mathbb R^d)} \leq C_p\|f\|_{L^p(\mathbb R^d)}.\] This inequality is often called in the literature the strong type \((p,p)\) inequality for the Hardy–Littlewood maximal function or we simply say that \(M_*f\) satisfies \(L^p\) bounds.

Remark.

-

One can check that this inequality fails, when \(p=1\). Justify this!

Proof. If \(p=\infty\) there is nothing to do. Assume that \(p<\infty\) and \(f \geq 0\).

-

Define \[f=f\mathbf{1}_{{F_{\alpha}}}+f\mathbf{1}_{{F_\alpha^c}}=f_\alpha+f^\alpha,\] where \[F_{\alpha}=\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: f(x) \leq \alpha\}.\]

-

By the triangle inequality \[M_*f \leq M_*f_\alpha+M_*f^\alpha.\]

-

Thus \[\begin{aligned} &\lambda_d(\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_* f(x) > 2\alpha\}) \\ &\qquad\leq \lambda_d(\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_* f_\alpha(x)+M_*f^\alpha(x) > 2\alpha\})\\ &\qquad \leq \lambda_d(\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_* f_\alpha(x)> \alpha\})\\ &\qquad+ \lambda_d(\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_*f^\alpha(x) > \alpha\}). \end{aligned}\]

-

Note that \(\lambda_d(\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_* f_\alpha(x)> \alpha\})=0\), since \(M_* f_\alpha(x)\le \alpha\).

-

Consequently, by the Layer-cake decomposition and change of variables we obtain \[\begin{aligned} \|M_*f\|_{L^p(\mathbb R^d)}^p &=p\int_0^{\infty}\alpha^{p-1}\lambda_d(\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_* f(x) > \alpha\}) \,d\alpha\\ &=2^pp\int_0^{\infty}\alpha^{p-1}\lambda_d(\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_* f(x) > 2\alpha\}) \,d\alpha\\ &\le 2^pp\int_0^{\infty}\alpha^{p-1}\lambda_d(\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_* f^{\alpha}(x) >\alpha\}) \,d\alpha \end{aligned}\]

-

Note also that \(f^{\alpha}\in L^1(\mathbb R^d)\). Indeed \(f^{\alpha}=f\mathbf{1}_{{F_{\alpha}^c}}\), and consequently \[\begin{aligned} \|f^{\alpha}\|_{L^1(\mathbb R^d)}=\int_{F_{\alpha}^c}|f(x)|\,dx \leq \frac{1}{\alpha^{p-1}}\int_{\mathbb{R}^d}|f(x)|^p\,dx =\frac{1}{\alpha^{p-1}}{\|f\|_{L^p(\mathbb R^d)}^p}. \end{aligned}\]

-

We apply the weak type \((1,1)\) inequality for the Hardy–Littlewood maximal function to conclude that \[\begin{aligned} 2^pp\int_0^{\infty}\alpha^{p-1}&\lambda_d(\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d:M_* f^{\alpha}(x) \geq 2\alpha\}) \,d\alpha\\ &\leq C_p2^pp\int_0^{\infty}\alpha^{p-2}\int_{\mathbb R^d} |f^\alpha(x)|\,dx \,d\alpha\\ &= C_p2^pp\int_0^{\infty}\alpha^{p-2}\int_{F_{\alpha}^c} |f(x)|\,dx \,d\alpha\\ &\le C_p2^pp \int_{\mathbb{R}^d}|f(x)|\int_0^{|f(x)|}\alpha^{p-2}\,d\alpha\,dx \quad \text{ (by Fubini) }\\ &=\frac{C_p 2^pp}{p-1}\int_{\mathbb{R}^d}|f(x)|^{p-1}|f(x)|\,dx\\ &=\frac{C_p 2^pp}{p-1}\|f\|_{L^p}^p. \end{aligned}\]

-

This completes the proof. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

A first glimpse at the Lebesgue differentiation theorem

For \(d\in \mathbb N\), let \[ M_rf(x)=\frac{1}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}\int_{B(x,r)}f(y)\,dy, \quad x\in \mathbb R^d, \quad f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb{R}^d)\] be the Hardy–Littlewood averaging operator. If \(f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb R^d)\), then \[\lim_{r \to 0}M_rf(x)=f(x)\quad \text{ for a.e. } \quad x \in \mathbb{R}^d.\]

Notation

-

In the proof we will use the following notion of the superior limit: \[ \limsup_{r \to R}\phi(r)=\lim_{\varepsilon \to 0}\sup_{0<|R-r|<\varepsilon}\phi(r)=\inf_{\varepsilon>0}\sup_{0<|r-R|<\varepsilon}\phi(r).\]

-

One can easily verify that \[\limsup_{r \to R}|\phi(r)-c|=0 \quad \iff \quad \lim_{r \to R}\phi(r)=c.\]

Proof. The proof illustrates a very important technique in establishing pointwise convergence.

-

Since \(f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}\) it suffices to show that for \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) we have \[\lim_{r \to 0}M_r f(x)= f(x)\quad \text{ a.e. on } \quad B(0,N).\]

-

But for \(|x| \leq N\) and \(r \leq 1\), the averaging operator \(M_rf(x)\) depends only on the values \(f(y)\) for \(|y| \leq N+1\) so by replacing \(f\) with \(f \mathbf{1}_{{B(0,N+1)}}\) we may assume that \(f \in L^1(\mathbb{R}^d)\).

-

Given \(\varepsilon>0\) we can find a continuous integrable function \(g\) such that \[\int_{\mathbb R^d} |g(y)-f(y)|\,dy<\varepsilon.\]

-

Continuity of \(g\) implies that for every \(x \in \mathbb{R}^d\) and \(\delta>0\) there exists \(r>0\) such that \(|g(y)-g(x)|<\delta\) whenever \(|x-y|<r\) and \[|M_rg(x)-g(x)|=\frac{1}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}\bigg|\int_{B(x,r)}(g(x)-g(y))\,dy\bigg|<\infty.\]

-

Thus \[\lim_{r\to 0}M_rg(x) =g(x)\quad \text{ for every } \quad x \in \mathbb{R}^d.\]

-

This immediately implies that \[\begin{aligned} \limsup_{r \to 0}&|M_rf(x)-f(x)|\\ &=\limsup_{r \to 0}|M_r(f-g)(x)+(M_rg(x)-g(x))+(g(x)-f(x))|\\ &\qquad\qquad \leq M_{*}(f-g)(x)+|f(x)-g(x)|. \end{aligned}\]

-

Hence if \(E_\alpha=\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: \limsup_{r \to 0}|M_rf(x)-f(x)|>\alpha\}\), and \[F_\alpha=\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: |f(x)-g(x)|>\alpha\}\] we have \[E_\alpha \subseteq F_{\alpha/2} \cup \{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: M_*(f-g)(x)>\alpha/2\}.\]

-

By Chebyshev’s inequality \[\lambda_d(F_{\alpha}) \leq \frac{2}{\alpha}\int_{F_{\alpha/2}}|f(x)-g(x)|\,dx < \frac{2\varepsilon}{\alpha}.\]

-

By the weak type \((1,1)\) inequality for the Hardy–Littlewood maximal function we obtain \[\lambda_d(E_\alpha) \leq \frac{2\varepsilon}{\alpha}+\frac{2C\varepsilon}{\alpha}.\]

-

Since \(\varepsilon>0\) is arbitrary \(\lambda_d(E_\alpha)=0\) for all \(\alpha>0\). Then \[\quad \lim_{r \to 0}M_rf(x)=f(x) \quad \text{ for all } \quad x \not\in \bigcup_{n \in \mathbb{N}}E_{1/n}, \quad \text{ so we are done}. \ \tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

Corollary

For \(d\in \mathbb N\), let \[ M_rf(x)=\frac{1}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}\int_{B(x,r)}f(y)\,dy, \quad x\in \mathbb R^d, \quad f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb{R}^d)\] be the Hardy–Littlewood averaging operator. If \(f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb R^d)\), then \[\lim_{r \to 0}\frac{1}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}\int_{B(x,r)}(f(y)-f(x))\,dy=0 \quad \text{ a.e. on } \quad \mathbb{R}^d.\]

Let us define the Lebesgue set \(L_f\) of \(f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb R^d)\) by \[L_f=\Big\{x \in \mathbb{R}^d: \lim_{r \to 0}\frac{1}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}\int_{B(x,r)}|f(y)-f(x)|\,dy=0\Big\}.\]

Lebesgue sets are measure zero sets

If \(f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb{R}^d)\), then \(\lambda_d(L_f^c)=0\).

Proof. For each \(c \in \mathbb{C}\) we apply Theorem (A) to \(g_c(x)=|f(x)-c|\) to conclude that except on a Lebesgue null set \(E_c\) we have \[\lim_{r \to 0}\frac{1}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}\int_{B(x,r)}|f(y)-c|\,dy=|f(x)-c|.\]

Let \(D\) be a countable and dense set in \(\mathbb{C}\) and let \(E=\bigcup_{c \in D}E_c\). Then \(\lambda_d(E)=0\). If \(x \not\in E\), for any \(\varepsilon>0\) we can find \(c \in D\) with \(|f(x)-c|<\varepsilon\) so that \(|f(x)-f(y)| \leq |f(y)-c|+\varepsilon.\) Hence \[\limsup_{r \to 0}\frac{1}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}\int_{B(x,r)}|f(y)-f(x)|\,dy \leq |f(x)-c|+\varepsilon<2\varepsilon,\] thus \(x \in L_f\). Hence \(L_f^c \subseteq E\) and \(\lambda_d(L_f^c)\le \lambda_d(E)=0\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Lebesgue differentiation theorem

A family of Borel sets \((E_r)_{r >0} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^d\) is said to shrink nicely to \(x \in \mathbb{R}^d\) if

-

\(E_r \subseteq B(x,r)\) for each \(r>0\),

-

there is \(\alpha>0\) independent of \(r>0\) such that \(\lambda_d(E_r) \geq \alpha \lambda_d(B(x,r))\).

Suppose \(f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb R^d)\). For every \(x\in L_f\), (\(L_f\) is the Lebesgue set of \(f\)), we have \[\lim_{r \to 0}\frac{1}{\lambda_d(E_r)}\int_{E_r}|f(y)-f(x)|=0,\] \[\lim_{r \to 0}\frac{1}{\lambda_d(E_r)}\int_{E_r}f(y)\,dy=f(x)\] for every \((E_r)_{r>0}\) that shrinks nicely to \(x \in \mathbb{R}^d\).

Regular measure

Proof. Since \(\lambda_d(L_f^c)=0\) we obtain \[\begin{gathered} \frac{1}{\lambda_d(E_r)}\int_{E_r}|f(y)-f(x)|\,dy \leq \frac{1}{\lambda_d(E_r)}\int_{B(x,r)}|f(y)-f(x)|\,dy\\ \qquad\qquad \qquad\leq \frac{1}{\alpha \lambda_d(B(x,r))}\int_{B(x,r)}|f(y)-f(x)|\,dy \ _{\overrightarrow{r\to 0}} \ 0 \qquad \qquad{\blacksquare} \end{gathered}\]

A Borel measure \(\nu\) on \(\mathbb{R}^d\) is called regular if

-

\(\nu(K)<\infty\) for every compact \(K \subseteq \mathbb{R}^d\),

-

\(\nu(E)=\inf\{\nu(U): E \subseteq U, \text{ and } U \text{ is open}\}\) for every \(E \in {\rm Bor}(\mathbb{R}^d)\).

Remark.

-

In fact, (ii) is implied by (i), and this definition of regular measures coincides with the regularity discussed at the beginning of the course.

-

A signed or complex Borel measure \(\nu\) is called regular if \(|\nu|\) is regular.

Theorem

Example. If \(f \in L_+^0(\mathbb{R}^d)\) then the measure \(f \,d\lambda_d\) is regular iff \(f \in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb{R}^d)\). Why?

Let \(\nu\) be a regular signed or complex Borel measure on \(\mathbb{R}^d\) and let \(d\nu=d\mu+f\,d\lambda_d\) be the Lebesgue–Radon–Nikodym decomposition. Then for \(\lambda_d\)-a.e. \(x \in \mathbb{R}^d\) we have \[\lim_{r \to 0}\frac{\nu(E_r)}{\lambda_d(E_r)}=f(x), \quad \text{ and } \quad \lim_{r \to 0}\frac{\mu(E_r)}{\lambda_d(E_r)}=0,\] for every family \((E_r)_{r >0} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^d\) that shrinks nicely to \(x\in \mathbb R^d\).

Proof. It is not difficult to see that \(d|\nu|=d|\mu|+|f|\,d\lambda_d\) so the regularity of \(\nu\) implies the regularity of both \(\mu\) and \(f\,d\lambda_d\).

-

Since \(f\in L^1_{{\rm loc}}(\mathbb R^d)\) so in view of the previous theorem it suffices to prove that if \(\mu\) is regular and \(\mu \perp \lambda_d\), then for a.e. \(x \in \mathbb{R}^d\) we have \[\lim_{r \to 0}\frac{\mu(E_r)}{\lambda_d(E_r)}=0.\]

-

It also suffices to take \(B_r=B(x,r)\) and assume \(\mu\) is positive since for some \(\alpha>0\) we have \[\left|\frac{\mu(E_r)}{\lambda_d(E_r)}\right| \leq \frac{|\mu|(E_r)}{\lambda_d(E_r)} \leq \frac{|\mu|(B(x,r))}{\alpha \lambda_d(B(r,r))}.\]

-

Assuming that \(\mu \geq 0\) let \(A \in {\rm Bor}({\mathbb{R}^d})\) such that \(\mu(A)=\lambda_d(A^c)=0\) and let \[F_k=\left\{x \in A: \limsup_{r \to 0}\frac{\mu(B(x,r))}{\lambda_d(B(x,r))}>\frac{1}{k}\right\}.\]

-

We shall show that \(\lambda_d(F_k)=0\) for all \(k \in \mathbb{N}\) and we will be done.

-

By regularity of \(\mu\) given \(\varepsilon>0\) there is an open \(U_\varepsilon \supseteq A\) such that \(\mu(U_\varepsilon)<\varepsilon\).

-

Each \(x \in F_k\) is the center of a ball \(B_{x} \subseteq U_\varepsilon\) and \(\mu(B_x)>\lambda_d(B_x)k^{-1}\).

-

By Vitali’s covering argument if \(V_\varepsilon=\bigcup_{x \in F_k}B_x\) and \(c<\lambda_d(V_\varepsilon)\) there are \(x_1,\ldots,x_J\) such that \(B_1,\ldots,B_J\) are disjoint and

\[\begin{gathered} c<3^d\sum_{j=1}^{J}\lambda_d(B_{x_j}) \leq 3^{d}k\sum_{j=1}^J \mu(B_{x_j}) \leq 3^dk\mu(V_\varepsilon)\\ \leq 3^d k \mu(U_\varepsilon) \leq 3^d k \varepsilon. \end{gathered}\]

-

We conclude that \(\lambda_d(V_\varepsilon) \leq 3^d k \varepsilon\) and since \(F_k \subseteq V_\varepsilon\) and \(\varepsilon>0\) is arbitrary then \(\lambda_d(F_k)=0\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$