12. Product measures PDF TEX

Product measures

Measurable rectangles

Let \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) and \((Y, \mathcal N,\nu)\) be measure spaces. Our aim is to construct a measure on \(\mathcal M \otimes \mathcal N\) that will be the product of \(\mu\) and \(\nu\).

Definition. A measurable rectangle is the set of the form \[A \times B \in \mathcal M \times \mathcal N= \{A \times B : A \in \mathcal M, \; B \in \mathcal N\}.\]

Remark. The collection \(\mathcal{A}\) of finite disjoint unions of rectangles from \(\mathcal M \times \mathcal N\) is an algebra, since \(\mathcal M \times \mathcal N\) is a semi-algebra, namely \[\begin{gathered} (A \times B) \cap (E \cap F)=(A \cap E) \times (B \cap F),\\ (A \times B)^c=(X \times B^c) \cup (A^c \times B). \end{gathered}\] Of course, \(\mathcal M \otimes \mathcal N=\sigma(\mathcal{A})=\sigma(\mathcal M \times \mathcal N),\) but \(\mathcal M \otimes \mathcal N \neq \mathcal M \times \mathcal N\).

Observation 1

Suppose \(A \times B\in \mathcal M \times \mathcal N\) is a rectangle that is a (finite or countable) disjoint union of rectangles \(A_j \times B_j\in \mathcal M \times \mathcal N\). Then for \((x,y) \in X \times Y\) \[\mathbf{1}_{{A}}(x)\mathbf{1}_{{B}}(y)=\mathbf{1}_{{A \times B}}((x,y))=\sum_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\mathbf{1}_{{A_j \times B_j}}((x,y)) =\sum_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\mathbf{1}_{{A_j}}(x)\mathbf{1}_{{B_j}}(y),\] If we integrate with respect to \(x\in X\) and use the (MCT), then \[\begin{aligned} \mu(A)\mathbf{1}_{{B}}(y)=\int_X &\mathbf{1}_{{A}}(x)\mathbf{1}_{{B}}(y)d\mu(x)\\ \underbrace{=}_{\text{(MCT)}}&\sum_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\int_X \mathbf{1}_{{A_j}}(x)\mathbf{1}_{{B_j}}(y)d\mu(x) =\sum_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\mu(A_j)\mathbf{1}_{{B_j}}(y). \end{aligned}\] If we integrate with respect to \(y\in Y\) and use the (MCT) again, then \[{\color{blue}\mu(A)\nu(B)=\sum_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\mu(A_j)\nu(B_j).}\]

From countably subadditive set functions to premeasures

Theorem. (From countably subadditive set functions to premeasures) Let \(\rho:\mathcal{E} \to [0,\infty]\) be a set function on a semi-algebra \(\mathcal{E}\) of subsets of a set \(X\) and \(\rho(\varnothing)=0\). Suppose that \(\rho\) is finitely additive on \(\mathcal{E}\) and let \(\mathcal{A}\) be the algebra that consists of all finite disjoint unions of members of \(\mathcal{E}\). Define a set function \(\mu_0\) on \(\mathcal{A}\) by setting \[\mu_0(A)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\rho(E_i)\] for \(A=\bigcup_{j=1}^{n}E_j \in \mathcal{A}\), where \(E_1,\ldots,E_n \in \mathcal{E}\) and \(E_i \cap E_j = \varnothing\) if \(i \neq j\).

-

Then \(\mu_0\) is a well-defined additive set function on \(\mathcal{A}\) such that \(\mu_0(\varnothing)=0\) and \(\mu_0=\rho\) on \(\mathcal{E}\).

-

If additionally \(\rho\) is countably subadditive on \(\mathcal{E}\) then \(\mu_0\) is a premeasure on \(\mathcal{A}\).

Observation 2

-

If \[E =\bigcup_{j=1}^nA_j \times B_j\in \mathcal{A}\] is the disjoint union of rectangles \(A_1 \times B_1, \ldots,A_n \times B_n\in \mathcal M \times \mathcal N\) and we set \[{\color{blue}\pi(E)=\sum_{j=1}^n\mu(A_j)\nu(B_j)}\] with the usual convention that \(0 \cdot \infty=0\), then \(\pi\) is well defined on \(\mathcal{A}\).

-

Moreover, \(\pi\) is a premeasure on \(\mathcal A\), since by Observation 1, it is countably additive on \(\mathcal M \times \mathcal N\).

Product of two measures

Since \(\pi\) is the premeasure on \(\mathcal{A}\), by the Caratheodory extension theorem, \(\pi\) generates an outer measure on \(X \times Y\) whose extension to \(\mathcal M \times \mathcal N\) is a measure that extends \(\pi\).

We call this measure the product of \(\mu\) and \(\nu\) and denote it by \(\mu \times \nu\).

Remark.

-

If \(\mu\) and \(\nu\) are \(\sigma\)-finite, then also \(\mu \times \nu\) is \(\sigma\)-finite.

-

In this case, \(\mu \times \nu\) is the unique measure on \(\mathcal M \otimes \mathcal N\) such that \[\mu \times \nu(A \times B)=\mu(A)\nu(B)\] for all rectangles \(A \times B \in \mathcal M \times \mathcal N\).

Product of finitely many measures

-

Suppose that \((X_j,\mathcal M_j,\mu_j)\) are measurable spaces \(1\le j\le n\). If we define a rectangle to be a set of the form \[A_1 \times \ldots \times A_n \in \prod_{j=1}^n\mathcal M_j=\{A_1 \times \ldots \times A_n: A_1\in \mathcal M_1,\ldots, A_n\in \mathcal M_n\},\quad\] then the collection \(\mathcal{A}\) of finite disjoint unions of rectangles from \(\prod_{j=1}^n\mathcal M_j\) is an algebra.

-

This algebra gives rise to the canonical premeasure as in the case of two factors, which produces a product measure \[\mu_1 \times \ldots \times \mu_n \quad \text{ on }\quad \mathcal M_1 \otimes \ldots \otimes \mathcal M_n\] such that \[\mu_1 \times \ldots \times \mu_n (A_1 \times \ldots \times A_n)=\prod_{j=1}^n\mu_j(A_j),\] for any \(A_1 \times \ldots \times A_n \in \prod_{j=1}^n\mathcal M_j\).

Remarks

-

If the \(\mu_j\)’s are \(\sigma\)-finite so that the extension from \(\mathcal{A}\) to \(\bigotimes_{j=1}^n\mathcal M_j\) is uniquely determined by the Caratheodory extension theorem.

-

Moreover, the obvious associativity holds. For example, if we identify \[X_1 \times X_2 \times X_3 \quad \text{ with } \quad (X_1 \times X_2) \times X_3\] we have \(\mathcal M_1 \otimes \mathcal M_2 \otimes \mathcal M_3=(\mathcal M_1 \otimes \mathcal M_2) \otimes \mathcal M_3,\) where

-

\(\mathcal M_1 \otimes \mathcal M_2 \otimes \mathcal M_3=\sigma(\mathcal M_1 \times \mathcal M_2 \times \mathcal M_3)\) and

-

\((\mathcal M_1 \otimes \mathcal M_2) \otimes \mathcal M_3=\sigma (\mathcal N\times \mathcal M_3)\), with \(\mathcal N=\mathcal M_1 \otimes \mathcal M_2\),

and we also have \[\mu_1 \times \mu_2 \times \mu_3=(\mu_1 \times \mu_2) \times \mu_3,\] since they agree on the sets of the form \(A_1 \times A_2 \times A_3\) and hence in general by the uniqueness.

-

Sections

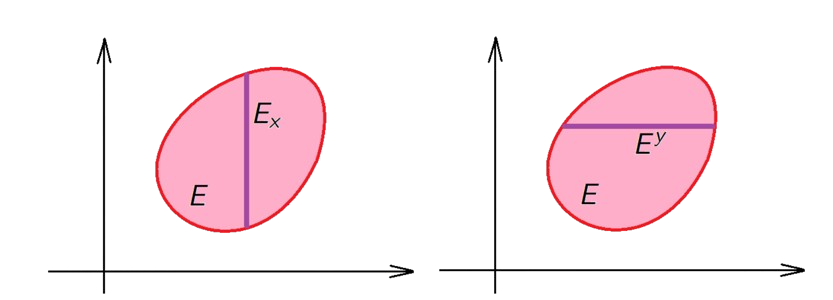

Let \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) and \((Y,\mathcal N,\nu)\) be measure spaces. If \(E \in X \times Y\), for \(x \in X\) and \(y \in Y\) we define the \(x\)-section of \(E\) and \(y\)-section of \(E\) by \[E_x=\{y \in Y: (x,y) \in E\}, \qquad \text{ and } \qquad E^y=\{x \in X: (x,y) \in E\}.\]

Sections of functions

If \(f\) is a function on \(X \times Y\) we define the \(x\)-section \(f_x\) and the \(y\)-section of \(f\) by \[f_x(y)=f^y(x)=f(x,y).\]

Example. \[(\mathbf{1}_{{E}})_x=\mathbf{1}_{{E_x}}, \qquad \text{ and } \qquad (\mathbf{1}_{{E}})^y=\mathbf{1}_{{E^y}}.\]

Proposition. Let \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) and \((Y,\mathcal N,\nu)\) be measure spaces.

-

If \(E \in \mathcal M \otimes \mathcal N\), then \(E_x \in \mathcal N\) for all \(x \in X\) and \(E^y \in \mathcal M\) for all \(y \in Y\).

-

If \(f\) is \(\mathcal M \otimes \mathcal N\)-measurable then \(f_x\) is \(\mathcal N\)-measurable for all \(x \in X\) and \(f^y\) is \(\mathcal M\)-measurable for all \(y \in Y\).

To prove the conclusion from the first item let \[\mathcal R=\{E \subseteq X \times Y: E_x \in \mathcal N \text{ for all } x \in X, \quad E^y \in \mathcal M \text{ for all } y \in Y\}.\] Then \(\mathcal M \times \mathcal N \subseteq R\), since \[(A \times B)_x=\begin{cases} B &\text{ if }x \in A,\\ \varnothing &\text{ if }x \not\in A, \end{cases} \quad \text{ and } \quad (A \times B)^y=\begin{cases} A &\text{ if } y \in B,\\ \varnothing &\text{ if }y \not\in B. \end{cases}\] Since \[\Big(\bigcup_{j=1}^\infty E_j\Big)_x=\bigcup_{j=1}^\infty (E_j)_x, \quad \text{ and } \quad (E^c)_x=E_x^c,\] and likewise for \(y\)-sections, thus \(\mathcal R\) is a \(\sigma\)-algebra and consequently \(\mathcal R \supseteq \mathcal M \otimes \mathcal N\). For the second item we use the first one and note that \[(f_x)^{-1}[B]=\{y \in Y : f_x(y) \in B\}=\{y \in Y : f(x,y) \in B\}=(f^{-1}[B])_x\] and similarly \((f^{y})^{-1}[B]=(f^{-1}[B])^y\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Monotone classes

A monotone class \(\mathcal{C}\) on a space \(X\) is a subset of \(\mathcal{P}(X)\) that is closed under countable increasing unions, that is

-

if \((C_n)_{n\in\mathbb N}\subseteq \mathcal C\) and \(C_1\subseteq C_2 \subseteq \ldots\), then \(\bigcup_{n\in\mathbb N}C_n\in\mathcal C\),

and countable decreasing intersections, that is

-

if \((C_n)_{n\in\mathbb N}\subseteq \mathcal C\) and \(C_1\supseteq C_2 \supseteq \ldots\), then \(\bigcap_{n\in\mathbb N}C_n\in\mathcal C\).

Remark.

-

Clearly, every \(\sigma\)-algabra is a monotone class.

-

Intersection of any family of monotone classes is a monotone class.

-

Intersection of all monotone classes containing \(\mathcal E\subseteq \mathcal P(X)\) is a unique smallest monotone class containing \(\mathcal E\).

The monotone class lemma

If \(\mathcal{A}\) is an algebra of subsets of \(X\) then the monotone class \(\mathcal{C}\) generated by \(\mathcal{A}\) coincides with the \(\sigma\)-algebra \(\mathcal M=\sigma(\mathcal{A})\).

Proof. Since \(\mathcal M\) is a monotone class, we have \(\mathcal C\subseteq \mathcal M\). We show that \(\mathcal C\) is a \(\sigma\)-algebra, yielding \(\mathcal M\subseteq \mathcal C\). For \(E\in \mathcal C\) let us define a monotone class \[\mathcal C(E)=\{F\in\mathcal C: E\setminus F \text{ and } F\setminus E \text{ and } E\cap F\in\mathcal C\}.\]

-

Clearly, \(\varnothing, E\in \mathcal C(E)\), since \(\mathcal A\subseteq \mathcal C\), and \(F\in \mathcal C(E)\) iff \(E\in \mathcal C(F)\).

-

If \(E\in \mathcal A\), then \(F\in \mathcal C(E)\) for all \(F\in \mathcal A\) because \(\mathcal A\subseteq \mathcal C\) is an algebra. Thus \(\mathcal A\subseteq \mathcal C(E)\) and \(\mathcal C\subseteq \mathcal C(E)\) for all \(E\in \mathcal A\).

-

If \(F\in \mathcal C\), then \(F\in \mathcal C(E)\) for all \(E\in \mathcal A\). Then \(E\in \mathcal C(F)\) for all \(E\in \mathcal A\), so that \(\mathcal A\subseteq \mathcal C(F)\) and hence \(\mathcal C\subseteq \mathcal C (F)\).

-

If \(E, F\in\mathcal C\), then \(F\setminus E, E\cap F\in\mathcal C\), since \(X\in\mathcal A\subseteq \mathcal C\) hence \(\mathcal C\) is an algebra. If \((E_j)_{j\in\mathbb N}\subseteq \mathcal C\) then \(\bigcup_{j=1}^nE_j\in\mathcal C\) but \(\mathcal C\) is closed under countable increasing unions thus \(\mathcal C\) is a \(\sigma\)-algebra as claimed. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Fundamental Theorem

Suppose \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) and \((Y,\mathcal N,\nu)\) are \(\sigma\)-finite measure spaces. If \(E \in \mathcal M \otimes \mathcal N\) then the functions \[x \mapsto \nu(E_x) \qquad \text{ and } \qquad y \mapsto \mu(E^y)\] are measurable on \(X\) and \(Y\) respectively and \[\mu \times \nu (E)=\int_X \nu(E_x)d\mu(x)=\int_Y \mu(E^y)d\nu(y).\]

Proof. First suppose that \(\mu\) and \(\nu\) are finite. Let \(\mathcal{C}\) be the collection of all \(E \in \mathcal M \otimes \mathcal N\) for which the conclusion of the theorem is true. If \(E =A \times B\) then \(\nu(E_x)=\mathbf{1}_{{A}}(x)\nu(B)\) and \(\mu(E^y)=\mu(A)\mathbf{1}_{{B}}(y)\) thus \(E \in \mathcal{C}\). By additivity it follows that finite disjoint unions of rectangles are in \(\mathcal{C}\). It suffices to show that \(\mathcal{C}\) is a monotone class and then the conclusion will follow by the monotone class lemma.

-

If \((E_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is an increasing sequence in \(\mathcal{C}\) and \[E=\bigcup_{j=1}^{\infty}E_j,\] then the functions \(f_n(y)=\mu((E_n)^y)\) are measurable and increase pointwise to \(f(y)=\mu(E^y)\).

-

Hence \(f\) is measurable and by the (MCT) we see \[\int_Y \mu(E^y)d\nu(y)=\lim_{n \to \infty}\int_Y \mu(E_n^y)d\nu(y) =\lim_{n \to \infty}\mu \times \nu(E_n)=\mu \times \nu (E).\]

-

Likewise \(\mu \times \nu(E)=\int_X \nu(E_x)d\mu(x)\) so \(E \in \mathcal{C}\).

-

Similarly, if \((E_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is a decreasing sequence in \(\mathcal{C}\) and \(\bigcap_{n=1}^{\infty}E_n=F\), the function \[y \mapsto \mu((E_1)^y)\in L^1(\nu)\] because \(\mu((E_1)^y) \leq \mu(X)<\infty \text{ and }\nu(Y)<\infty,\) so the (DCT) can be applied to show that \(F \in \mathcal{C}\).

-

Thus \(\mathcal{C}\) is a monotone class for the case of finite measure spaces.

-

If \(\mu\) and \(\nu\) are \(\sigma\)-finite, then \(X \times Y=\bigcup_{j \in \mathbb{N}}X_j \times Y_j\) for an increasing sequence of rectangles \((X_j \times Y_j)_{j \in \mathbb{N}}\) with \(\mu(X_j \times Y_j)<\infty\) for \(j \in \mathbb{N}\).

-

If \(E \in \mathcal M \otimes \mathcal N\) then invoking the finite measure case we see that \[\begin{aligned} \mu \times \nu(E \cap (X_j \times Y_j))&=\int_X \mathbf{1}_{{X_j}}(x)\nu(E_x \cap Y_j)d\mu(x)\\ &=\int \mathbf{1}_{{Y_j}}(y)\mu(E^y \cap X_j)d\nu(y). \end{aligned}\] By the (MCT) the claim follows for \(\sigma\)-finite measure spaces.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Tonelli’s Theorem

Suppose that \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) and \((Y,\mathcal N,\nu)\) are \(\sigma\)-finite measure spaces. If \(f \in L^0_+(X \times Y, \mu\times\nu)\) then \[\begin{aligned} g(x)&=\int_Y f_x(y)d\nu(y)\in L^0_+(X, \mu),\\ h(y)&=\int_X f^y(x)d\mu(x)\in L^0_+(Y, \nu), \end{aligned}\] and \[\begin{aligned} \int_{X\times Y} f(x, y)d(\mu \times \nu)(x, y) &=\int_X \left(\int_Y f(x,y)d\nu(y)\right)d\mu(x)\\ &=\int_Y \left(\int_X f(x,y)d\mu(x)\right)d\nu(y). \end{aligned}\]

-

Tonelli’s theorem reduces to the previous theorem in case \(f\) is a characteristic function and therefore holds for nonnegative simple functions by linearity. If \(f \in L^0_+(X \times Y)\) let \((f_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) be a sequence of simple functions that increase pointwise to \(f\). Let \[g_n(x)=\int_Y (f_n)_x(y)d\nu(y), \quad \text{ and }\quad h_n(y)=\int_X (f_n)^y(x)d\mu(x).\]

-

By the (MCT) \(g_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n\to \infty}} \ g\) and \(h_n \ _{\overrightarrow{n\to \infty}} \ h\), so that \(g\) and \(h\) are measurable and we have \[\begin{aligned} \int_X gd\mu=\lim_{n \to \infty}\int_X g_nd\mu =\lim_{n \to \infty}\int_{X\times Y} f_nd(\mu \times \nu) =\int_{X\times Y} fd(\mu \times \nu),\\ \int_Y hd\nu=\lim_{n \to \infty}\int_Y h_nd\nu =\lim_{n \to \infty}\int_{X\times Y} f_nd(\mu \times \nu) =\int_{X\times Y} fd(\mu \times \nu). \end{aligned}\] This proves Tonelli’s theorem.$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Fubini’s Theorem

Suppose that \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) and \((Y,\mathcal N,\nu)\) are \(\sigma\)-finite measure spaces. If \(f \in L^1(X \times Y, \mu\times\nu)\) then \(f_x\in L^1(Y, \nu)\) for \(\mu\)-a.e. \(x\in X\) and \(f^y\in L^1(X, \mu)\) for \(\nu\)-a.e. \(y\in Y\) and \[\begin{aligned} g(x)&=\int_Y f_x(y)d\nu(y)\in L^1(X, \mu),\\ h(y)&=\int_X f^y(x)d\mu(x)\in L^1(Y, \nu), \end{aligned}\] and \[\begin{aligned} \int_{X\times Y} f(x, y)d(\mu \times \nu)(x, y) &=\int_X \left(\int_Y f(x,y)d\nu(y)\right)d\mu(x)\\ &=\int_Y \left(\int_X f(x,y)d\mu(x)\right)d\nu(y). \end{aligned}\]

-

In Tonelli’s theorem if \[\int_{X\times Y} fd\mu \times \nu <\infty,\] then \[\begin{aligned} g(x)&=\int_Y f_x(y)d\nu(y)<\infty, \quad \mu-\text{a.e.},\\ h(y)&=\int_X f^y(x)d\mu(x)<\infty, \quad \nu-\text{a.e.}, \end{aligned}\] that is \(f_x \in L^1(Y, \nu)\) for a.e. \(x\in X\) and \(f^y \in L^1(X, \mu)\) for a.e. \(y\in Y\).

-

If \(f \in L^1(X\times Y, \mu \times \nu)\) then the conclusion of Fubini’s theorem follows by applying Tonelli’s theorem and these results to the positive and negative parts of the real and imaginary parts of \(f\). $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Remarks

-

\(\sigma\)-finiteness is necessary in both Tonelli’s and Fubini’s theorems.

-

The Fubini and Tonelli theorems are frequently used in tandem. To reverse the order of integration in a double integral \(\int_{X\times Y}fd\mu d\nu\), we first verify that \(\int_{X\times Y}|f|d\mu d\nu<\infty\) by using Tonelli’s theorem to evaluate this integral as an iterated integral; then one applies Fubini’s theorem to conclude that \(\int_Y\int_{X}fd\mu d\nu=\int_X\int_{Y}fd\nu d\mu\).

-

If \(\mu\) and \(\nu\) are complete \(\mu \times \nu\) is almost never complete. Suppose that there is \(A \in \mathcal M\) and \(\mu(A)=0\) and \(\mathcal N \neq \mathcal{P}(Y)\) (think that \(\mu=\nu=\lambda\) is the Lebesgue measure on \(\mathbb{R}\)). If \(E \in \mathcal{P}(Y) \setminus \mathcal N\), then \(A \times E \not\in \mathcal M \otimes \mathcal N\) but \(A \times E \subseteq A \times Y\) and \(\mu \times \nu(A \times Y)=0\).

-

If one wishes to work with complete measures, of course, one can consider the completion of \(\mu\times \nu\). In this setting the relationship between the measurability of a function on \(X \times Y\) and the measurability of its \(x\)-sections and \(y\)-sections is not so simple. However, the Fubini–Tonelli theorem is still valid when suitably reformulated.

Completion of product spaces

For a given \(d\in \mathbb N\) let \((X_j, \mathcal M_j, \mu_j)\) be a measure space for each \(1\le j\le d\). Let \((X_j, \overline{\mathcal M_j}, \overline{\mu_j})\) be a completion of \((X_j, \mathcal M_j, \mu_j)\). Then one has \[\bigg(\prod_{j=1}^dX_j, \overline{\sigma\Big(\prod_{j=1}^d\mathcal M_j\Big)}, \overline{\bigotimes_{j=1}^d\mu_j}\bigg)= \bigg(\prod_{j=1}^dX_j, \overline{\sigma\Big(\prod_{j=1}^d\overline{\mathcal M_j}\Big)}, \overline{\bigotimes_{j=1}^d\overline{\mu_j}}\bigg).\]

Proof. If \((X, \mathcal M, \mu)\) is a measure space, then \[\overline{\mathcal M}=\{A\cup B: A\in \mathcal M \text{ and } B\subseteq C\in \mathcal M \text{ and } \mu(C)=0\}.\] Since \(\mathcal M_j\subseteq \overline{\mathcal M_j}\) for each \(1\le j\le d\), then \[\sigma\Big(\prod_{j=1}^d\mathcal M_j\Big)\subseteq \sigma\Big(\prod_{j=1}^d\overline{\mathcal M_j}\Big) \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \overline{\sigma\Big(\prod_{j=1}^d\mathcal M_j\Big)}\subseteq \overline{\sigma\Big(\prod_{j=1}^d\overline{\mathcal M_j}\Big)}.\]

It suffices to show that \[\prod_{j=1}^d\overline{\mathcal M_j}\subseteq \overline{\sigma\Big(\prod_{j=1}^d\mathcal M_j\Big)} \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \overline{\sigma\Big(\prod_{j=1}^d\overline{\mathcal M_j}\Big)} \subseteq\overline{\sigma\Big(\prod_{j=1}^d\mathcal M_j\Big)}.\]

-

If \(E_j\in\overline{\mathcal M_j}\) then \(E_j=A_j\cup B_j\), where \(A_j\in\mathcal M_j\) and \(B_j\subseteq C_j\in\mathcal M_j\) and \(\mu_j(C_j)=0\). Define \[P_j=F_{j, 1}\times\ldots\times F_{j, d} \quad \text{ where } \quad F_{j, k}= \begin{cases} A_k\cup B_k & \text{ for } k\neq j,\\ B_j & \text{ for } k=j, \end{cases}\] and \[Q_j=G_{j, 1}\times\ldots\times G_{j, d} \quad \text{ where } \quad G_{j, k}= \begin{cases} A_k\cup C_k & \text{ for } k\neq j,\\ C_j & \text{ for } k=j. \end{cases}\]

-

Then \[\prod_{j=1}^dE_j=\prod_{j=1}^d(A_j\cup B_j)=\prod_{j=1}^dA_j\cup\bigcup_{j=1}^dP_j.\] Now \(\prod_{j=1}^dA_j\in \prod_{j=1}^d\mathcal M_j\) and \(\bigcup_{j=1}^dP_j\subseteq \bigcup_{j=1}^dQ_j\in \prod_{j=1}^d\mathcal M_j\) and \[\Big(\bigotimes_{k=1}^d\mu_k\Big)\Big(\bigcup_{j=1}^dQ_j\Big)\le \sum_{j=1}^d\Big(\bigotimes_{k=1}^d\mu_k\Big)(Q_j) \le \sum_{j=1}^d\prod_{k=1}^d\mu_k(G_{j, k})=0,\] since \(\mu_k(G_{k, k})=\mu_k(C_k)=0\).

-

Thus we have shown that \(\bigcup_{j=1}^dP_j\) is a subset of a null set \(\bigcup_{j=1}^dQ_j\) in a product space \(\big(\prod_{j=1}^dX_j, \sigma\big(\prod_{j=1}^d\mathcal M_j\big), \bigotimes_{j=1}^d\mu_j\big)\), as desired. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Observation

Let \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) and \((Y,\mathcal N,\nu)\) be two measure spaces. If \(E\) is a null set in the product space \((X\times Y,\sigma(\mathcal M\times \mathcal N),\mu\times \nu)\) then

-

\(E_x\) is a null set in \((Y,\mathcal N,\nu)\) for \(\mu\)-a.e. \(x\in X\).

-

\(E^y\) is a null set in \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) for \(\nu\)-a.e. \(y\in Y\).

Proof. We have \[\int_X \nu(E_x)d\mu(x)=\int_Y \mu(E^y)d\nu(y)=\mu \times \nu (E)=0.\] Thus \[\nu(E_x)\ge0 \quad \text{ and } \quad \int_X \nu(E_x)d\mu(x)=0,\] yielding \(\nu(E_x)\) for \(\mu\)-a.e. \(x\in X\). Similarly, \(\mu(E^y)\) for \(\nu\)-a.e. \(y\in Y\).$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

Useful fact

Proposition. Let \((X\times Y,\overline{\sigma(\mathcal M\times \mathcal N)},\mu\times \nu)\) be the completion of the product space \((X\times Y,\sigma(\mathcal M\times \mathcal N),\mu\times \nu)\) of two complete measure spaces \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) and \((Y,\mathcal N,\nu)\).

-

If \(E\in \overline{\sigma(\mathcal M\times \mathcal N)}\), then \(E_x\in \mathcal N\) for \(\mu\)-a.e. \(x\in X\) and \(E^y\in \mathcal M\) for \(\nu\)-a.e. \(y\in Y\).

-

If \(f\) is an extended real-valued \(\overline{\sigma(\mathcal M\times \mathcal N)}\)-measurable function on \(X\times Y\), then \(f_x\) is \(\mathcal N\)-measurable for \(\mu\)-a.e. \(x\in X\) and \(f^y\) is \(\mathcal M\)-measurable for \(\nu\)-a.e. \(y\in Y\).

Proof. It suffices to prove (b), the (a) will follow by taking \(f=\mathbf{1}_{{E}}\) for \(E\in \overline{\sigma(\mathcal M\times \mathcal N)}\). An important tool in proving (b) is the following result:

Proposition. Let \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) be a measurable space and let \((X,\overline{\mathcal M},\overline{\mu})\) be its completion. If \(f\) is \(\overline{\mathcal M}\)-measurable function on \(X\), there is \(\mathcal M\)-measurable function \(g\) such that \(f=g\) \(\overline{\mu}\)-a.e., in fact \(f=g\) on \(N^c\) for some null set \(N\in\mathcal M\).

If \(f\) is \(\overline{\sigma(\mathcal M\times \mathcal N)}\)-measurable then there are a \(\sigma(\mathcal M\times \mathcal N)\)-measurable function \(g\) and a null set \(E\in \sigma(\mathcal M\times \mathcal N)\) such that \(f=g\) on \(E^c\). Then

-

\(f_x=g_x\) on \(E_x^c\) for \(x\in X\),

-

\(f^y=g^y\) on \((E^y)^c\) for \(y\in Y\).

Now \(g_x\) is \(\mathcal N\)-measurable for every \(x\in X\). By the previous observation \(E_x\) is a null set in a complete measure space \((Y,\mathcal N,\nu)\) for \(\mu\)-a.e. \(x\in X\). Thus \(f_x\) is \(\mathcal N\)-measurable for \(\mu\)-a.e. \(x\in X\). Similarly, we have \(f^y\) is \(\mathcal M\)-measurable for \(\nu\)-a.e. \(y\in Y\), and the proof is completed. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

-

Using this proposition and previous observation we can readily prove the following Fubini–Tonelli theorem for complete measure spaces.

Fubini–Tonelli theorem for complete measure spaces

Let \((X,\mathcal M,\mu)\) and \((Y,\mathcal N,\nu)\) be complete \(\sigma\)-finite measure spaces and let \((X \times Y,\mathcal T, \theta)\) be the completion of \((X \times Y, \mathcal M \otimes\mathcal N,\mu \times \nu)\). If \(f\) is \(\mathcal T\)-measurable and either: (a) \(f \geq 0\), or (b) \(f \in L^1(\theta)\). Then \(f_x\) is \(\mathcal N\)-measurable for a.e. \(x\) and \(f^y\) is \(\mathcal M\)-measurable for a.e. \(y\)., and in case (b) \(f_x\) and \(f^y\) are also integrable for a.e. x and y. Moreover, \[\begin{aligned} g(x)=\int_Y f_x(y)d\nu(y),\quad \text{ and } \quad h(y)=\int_X f^y(x)d\mu(x), \end{aligned}\] are measurable and in case (b) also integrable, and \[\begin{aligned} \int_{X\times Y} f(x, y) d\theta(x, y)&=\int_X\bigg(\int_Y f(x,y)d\nu(y)\bigg)d\mu(x)\\ &=\int_Y\bigg(\int_X f(x,y)d\mu(x)\bigg)d\nu(y). \end{aligned}\]